Will Streetcar Help The Inner City?

Opponents say it won’t. Let’s examine the data.

One charge made by critics of the Milwaukee streetcar project is that it won’t help inner city residents. Are they right?

The current issue of Milwaukee Magazine has an article by Barbara Miner with a series of interviews of residents of ZIP code 53206, the area bordered by North Avenue on the south, the I-43 and 17th St. on the west, Capitol Drive on the north, and 27th Street on the west. Miner chose it because it’s “often dismissed as the poorest and most troubled neighborhood in Milwaukee.”

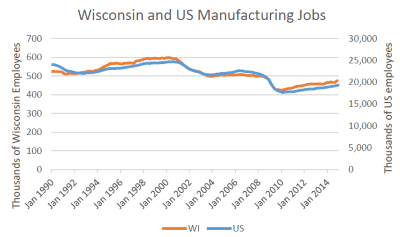

The story’s dominant theme is the devastation that resulted from the loss of manufacturing jobs, including Tower automotive and the other factories that once operated along Capitol Drive and the 35th Street Corridor.

The 53206 neighborhood has also come under considerable statistical study, including a recent report from Marc Levine of the UWM Center for Economic Development entitled Zipcode 53206: A Statistical Snapshot of Inner City Distress in Milwaukee: 2000-2012. Earlier, Lois M. Quinn of the UWM Employment and Training Institute, authored a report entitled New Indicators of Neighborhood Need in Zipcode 53206.

This loss of manufacturing jobs is not unique to Milwaukee. It occurred in most other American cities, especially in the industrial Midwest. It seems to have two main causes: globalization and a growing “spatial mismatch” between jobs and potential workers.

Globalization has meant that manufacturing jobs have moved out of Wisconsin and overseas in search of radically lower wage rates. The spatial mismatch reflects the fact that new factories are often built away from cities where land prices are cheap, large parcels can often be put together by buying one or two farms, and there is no need to clean up after a previous industrial user.

A 2011 Brookings Institution study looked at the spatial mismatch between low-skill job opportunities and welfare recipients in four metropolitan areas: Chicago, Los Angeles, Cleveland, and Milwaukee. All four showed the same pattern: large centers of low-skilled jobs far away from neighborhoods where the potential workers lived. But Milwaukee and Cleveland fared slightly better: “The distance between low-skill jobs and poor female-headed households seems greatest in LA and Chicago,” partly reflecting their greater size, the study noted. In most cases these job hubs were impossible to reach by public transportation.

Brookings published several reports on this issue in the 2011-2012 period. Milwaukee fared surprisingly well compared to other metropolitan areas. Among the largest 100 metropolitan areas, it rates in the middle in the share of working-age residents with access to transit, 8th in the share of jobs accessible within 90 minutes via transit, and 14th on a combined score for job access.

In December 2013, Milwaukee’s Public Policy Forum published a study of the difficulties of reaching suburban job hubs here. Again, most were impossible to reach by public transportation. While most of Milwaukee county was well-covered by public transit, that was not true of Oak Creek and Franklin where the only services were aimed more at suburban residents commuting downtown than at Milwaukee residents holding jobs in those cities. Likewise the only service to Ozaukee County was aimed at students attending MATC and stopped in the summer. Waukesha County transit served a limited part of that county, mostly in and around the city of Waukesha. To use It, Milwaukee County transit had to transfer at Brookfield Square, leading to very long commutes.

The PPF report concluded by examining three possible new routes: between Oak Creek and Mequon via downtown, an express route from UW-Milwaukee via downtown to Brookfield Square, and a third to the Westridge Business Park in Mequon. The first proposal was estimated to cost an additional $540,000 per year, the second about $1.25 million per year, and the third $635,000. Thus all would require additional financing.

The PPF listed some of the obstacles to route expansion to reach suburban job hubs. Notably many suburban industrial sites were isolated from other land uses that generate transit riders, so the routes were unable to generate sufficient ridership, making this impractical. Though federal funding might be available, the routes would be difficult to sustain once that funding ran out.

Some opponents seem under the impression—or are deliberately spreading the misinformation—that funds for the streetcar would be available for suburban bus routes if the streetcar were not built. This delusion seems to be shared by Lawrence Hanley, the International President of the Amalgamated Transit Union who writes from Washington, DC, to oppose the streetcar even though it “will undoubtedly create many jobs for our members.” Instead, he argues that “your resources would be more wisely spent on the expansion of your bus network.“

Apparently no one bothered to tell Hanley that the funds would simply disappear. The major federal grant, left over from the cancellation of the Park East Freeway more than 30 years ago, is restricted by federal legislation to the streetcar. The other major planned source of funding—tax incremental financing—is dependent on increased downtown property values resulting from the streetcar. Without the streetcar, tax incremental financing goes away as well.

It appears that Hanley has cribbed a page from the Scott Walker playbook. When cancelling the train to Madison, Walker argued to Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood that he should be allowed to spend the money on highways. Of course, LaHood could not legally do so, even if he had been so inclined. Instead the money went to other states.

Hanley seems to share the Scott Walker view that public transportation is only for riders who have no other choices. This is the same view that I heard Scott Walker express about public transportation as county executive. In fact in Hanley’s letter he disparages “’choice riders’ – including tourists and others who can afford to drive.”

A second solution, allowing workers to live closer to the jobs, seems even less likely in the foreseeable future, given the widespread hostility to affordable housing among Milwaukee’s suburban neighbors.

That would seem to leave only one strategy: increasing jobs in areas already well served by public transportation, so that people living in ZIP codes like 53206 can travel to them. The Public Policy Forum report includes a map of ZIP codes in the metropolitan area color coded according to the number of jobs they have. Superimposed on this map are bus routes, shown in green.

To the right is the section of the map that includes 53206 and downtown Milwaukee. 53206 is the pale rectangle to the northwest of downtown. Its pale color reflects the small number of jobs in the neighborhood—about 2,000, compared to about 14,000 residents between 20 and 64. Most of its residents must look elsewhere for jobs.

The best solution would be jobs within the 53206 neighborhood or the adjacent 35th street corridor. A start was the Talgo train project on the former Tower property, but that was killed by Gov. Walker and the state legislature.

However, a major asset of the 53206 neighborhood is its coverage by public transport (the green lines in the map), offering quick trips to Downtown.

Now consider the ZIP code that includes most of the initial streetcar route: 53202, Downtown east of the river. The PPF report includes a list of the job centers with at least 10,000 jobs. 53202 topped the list with 58,235 jobs in 2011.

If one adds in the three other downtown zip codes, 53203, 53204, and 53233, the number of downtown jobs rises to 118,000. Between 2004 and 2011, a period when jobs overall were declining, employment in the four ZIP codes grew by 6.7 percent.

In their search for employment, residents of 53206 spend much more time traveling than do other Milwaukee or suburban residents, according to numbers developed by Marc Levine. Only slightly over 2 percent of those living in 53206 find jobs within that ZIP code. By comparison, about one-quarter work in one of the four downtown ZIP codes.

On the first question, predictions about outcomes are always tricky, but there is considerable evidence that it would. It would tie together the downtown area in a very public fashion, allowing office workers to go to restaurants without worrying about parking (full disclosure: I plan to use it to get from my office at the northern edge of the route to a coffee shop in the Third Ward). At least two development projects appear contingent on the project. The very fact that it would be funded by incremental property taxes implies an increase in property values resulting from greater activity downtown.

In preparing a previous article I discovered that West Coast companies were trawling the Midwest for places to expand that had neighborhoods similar to those in their home cities. The only places in Wisconsin that passed the screen turned out to be in Milwaukee County. The streetcar would strengthen that appeal.

On the second question, it is important to recognize that a more dynamic Downtown will require people in a wide variety of occupations, not all with advanced degrees. The trick will be to make sure there will be mechanisms to connect the residents of 53206 to those opportunities. But the data indicate that the success of 53206 and Milwaukee’s downtown are already closely linked.

Streetcar Renderings and Maps

More about the Milwaukee Streetcar

For more project details, including the project timeline, financing, route and possible extensions, see our extensive past coverage.

- FTA Tells Milwaukee to Crack Down on Fare Evasion — Even Where Fares Don’t Exist - Graham Kilmer - Dec 12th, 2025

- Alderman, State Allies Seek Federal Help to Kill the Streetcar - Jeramey Jannene - Oct 28th, 2025

- Streetcar Service Suspended Following Truck Crash - Jeramey Jannene - Oct 21st, 2025

- One Alderman’s Quest To Defund The Streetcar - Jeramey Jannene - Oct 18th, 2025

- Another Streetcar Collision - Jeramey Jannene - Jun 27th, 2025

- Streetcar Hit By Apparent Red Light Runner - Jeramey Jannene - Jun 16th, 2025

- Streetcar Will Run On Consolidated Route During Summerfest - Jeramey Jannene - Jun 11th, 2025

- City Hall: Milwaukee Must Replace Failing Streetcar Switches - Jeramey Jannene - Feb 24th, 2025

- Streetcar Confronts Limited Funding, Operations Challenges - Evan Casey - Jan 22nd, 2025

- Council Kills Streetcar’s ‘Festivals Line’ - Jeramey Jannene - Jul 31st, 2024

Read more about Milwaukee Streetcar here

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Glad you mentioned this as it is direct evidence against the naysayers’ false choice argument about city priorities. The city has worked hard to cultivate the 30th St corridor at the same time they’ve been working on the streetcar.

This will help the inner city because it’ll increase densities, spark development and improve property values. Remember, the state takes all our income tax revenue, all our sales tax revenue and a chunk of our property tax revenue, while returning less and less back to Milwaukee. Much of this added revenue that the streetcar will help generate will go to help the inner city.

Milwaukee needs to increase its tax base because its being strangled. WCD, Mary Glass, Joe Davis and Bob Donavan need to get out of the way. None of these individuals have Milwaukee’s best interests in mind. Joe Davis wants to run for mayor and sees this issue as a way to build his campaign chest, WCD wants to destroy Milwaukee for political reasons, Mary Glass is ONLY interested in herself and has been strong arming the black community for years and Bob Donovan…. well I’m not sure what his story is.

It’s time to build.

“@ Bruce Thompson: Just a point of clarification regarding the source of the Federal funds for the Streetcar project. The $54.9 million in Interstate Cost Estimate (ICE) funds are part of larger $288.8 million dollar grant made in 1991 by the Federal government as part of the ISTEA transportion bill. Rather than being the result of the cancellation of the Park East freeway, these funds were provided for the last remaining piece of the interstate freeway system in Southeastern Wisconsin that was unbuilt at the time–a two-lane bus rapid transit (BRT) busway in the I-94 east-west corridor. That busway project was officially designated as an unbuilt part of the interstate highway system, because it was recommended by the Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission in its 1990 regional transportation plan for Southeastern Wisconsin completed in 1966, and Milwaukee County conducted and completed preliminary engineering on the busway in 1971, but chose not to move forward with the busway.

By 1999, $47.8 million of the $288.8 million had been pulled back by USDOT. In 1999, Mayor Norquist, Governor Thompson, County Executive Ament agreed that the remaining $241 million would be divided in the following way: $51 million for the Sixth Street Viaduct reconstruction, $21.3 million to tear down the Park East freeway spur and construct replacement surface streets, $2.0 million for a walkway at Lakeshore State Park, and $75.2 million for the Marquette Interchange. The remaining $91.5 was designated for a transit project that would be agreed upon by the Mayor and County Executive of Milwaukee.

A decade later, in 2009, Congress assigned 60 percent ($54.9 million) of the remaining $91.5 million to the “Milwaukee Downtown Connector Streetcar project” and 40 percent to a Milwaukee County for bus improvements. This money was used to purchase new buses for MCTS, and only the $54.9 million of the original $289 million is left to be spent.

The Washington DC Streetcar is already in trouble.

What makes Milwaukee different?

http://www.nbcwashington.com/news/local/DCs-Planned-37-Mile-Street-Car-System-in-Jeopardy-290843881.html

Ah, Milwaukee is not Washington, DC, for one. That’s a big difference. Janice you need a new hobby.

@Bruce Thompson,

Would you share the article discussing the West Coast companies that found Milwaukee county to be the only county that fit with expansion plans?

I would love to share that with some real estate friends and colleagues.

John G.,

It was not an article; rather an email exchange. Here is what Mr. McDermott wrote:

Regarding the target audience – corporations considering relocation decisions is part of, but not the entire target audience. While we work with many companies relocating operations outright, many more of our projects are with companies expanding into new locations. In the white collar sector, access to labor is paramount. It is somewhat rare for established, successful companies to completely pull up stakes due to the massive disruption it has on its employees. Instead, we find companies are looking for new locations with an atmosphere similar to their current home city. Quite often we see successful West Coast companies looking for that “little bit of San Francisco” in the lower-cost and less competitive Midwest. Cities that boast large populations of educated and urban-centric millennials tend to do well in our location screening.