Is California the Future?

The data about California may have political and economic lessons for Wisconsin.

In 2002, John Judis and Ruy Teixeira wrote a book entitled The Emerging Democratic Majority, in which they argued that Democrats would enjoy an increasing demographic advantage in American elections. This was largely based on the observation that minority groups were growing at a much higher rate than white Americans. The Census Bureau projects that by 2040, America will become a “majority minority” country, in which white Americans will be a minority.

For a time, elections seemed to bear out this thesis, including the 2006 wave election in which Democrats took control of both the US Senate and the House, followed by Barack Obama’s election as president. Later, however, elections have not followed its expectations, with the Republican “wave” off-year elections in 2010 and 2014 and Donald Trump’s election in 2016.

Judis now argues that he and Teixeira were wrong, while Teixeira continues to argue that the growth of minorities will ultimately shift the political balance towards the Democrats.

However the theory is borne out in future elections, Judis and Teixeira’s thesis seems to have had a profound effect on the right and the left. For the left, it encouraged Democrats to ignore the concerns of the white working class, perhaps contributing to Hillary Clinton’s loss in Wisconsin, by promoting the notion that it was becoming increasingly irrelevant.

It also contributed to a sense of panic, both on the right and among some members of the white working class. Here is the opening paragraph of a pro-Trump article published anonymously during the campaign:

2016 is the Flight 93 election: charge the cockpit or you die. You may die anyway. You—or the leader of your party—may make it into the cockpit and not know how to fly or land the plane. There are no guarantees.

The author, later identified as Michel Anton who went on to become a national security adviser in the Trump administration, went on to argue that:

… the ceaseless importation of Third World foreigners with no tradition of, taste for, or experience in liberty means that the electorate grows more left, more Democratic, less Republican, less republican, and less traditionally American with every cycle.

Perhaps this sense that America was becoming less American contributed both to the election of Trump and the Republican willingness to make states like Wisconsin less democratic to avert the looming disaster. If the alternative to radical gerrymandering and disenfranchising voters is to allow democracy to slip away, such measures may be justified, in this thinking.

Judis and other critics of the prediction that demographic change guaranteed success to Democrats pointed to several major flaws. One is that it assumes that children of people who self-identify today as Hispanic or Asian will continue to claim those identities. Another is the assumption that the political preferences of demographic groups are fixed and don’t change over time. Finally, it assumes that today’s political preferences of young people will remain fixed over time. Some of us remember a time when it was widely expected the baby boom generation would be far more liberal than their parents.

The emerging Democratic majority thesis has been revived and revised in the so-called California essays, written by Peter Leyden with Ruy Teixeira. Leyden argues that “California Is the Future of American Politics.” He goes on to assert that “Trump is the last gasp of the conservative era and will bring down Republican rule. What’s coming next is in California right now.”

Even if one assumes that the present political preferences by demographic groups will remain fixed over time, states like Wisconsin are way down on the list of those shifting to majority minority status. If any of the many Democratic candidates for Wisconsin governor are depending on this shift, they are living in a fantasy world. For Democrats to be viable in this (and many other states), they will need to win the votes—and address the issues–of a large number of working class white voters.

In addition to arguing that the rest of the nation is poised to follow in California’s footsteps, Leyden argues that this is a good thing. Most conservatives would, on the other hand, likely regard that as a terrible outcome. Let’s take a look at the record.

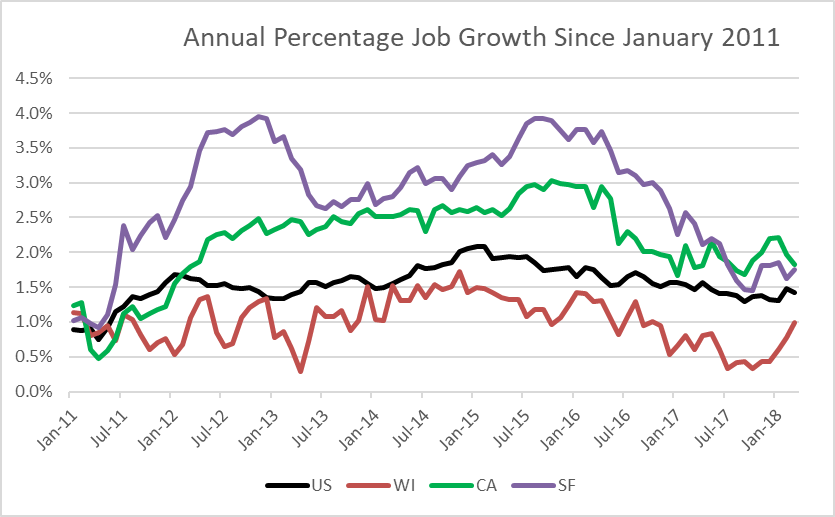

Start with job growth. If one believes that increasing the number of jobs is the most important role a state can play—as Wisconsin’s Scott Walker appears to believe—California is a clear success story. The chart below shows the percentage of job growth since January 2011 in Wisconsin, the US, California, and San Francisco. Both Walker and California’s Jerry Brown took office in 2011.

By this yardstick, at least, Brown is a far more successful governor than Walker. And as Leyden describes in some detail, California job growth was not promoted by sacrificing environmental protection. To the contrary, the state has taken the lead in countering global warming.

California also shows that conventional economic success has costs. As the next graph shows, compared to Milwaukee, the housing cost in California cities is astronomical. Part of the explanation is geography. Squeezed between the ocean and the mountains, California’s cities can’t spread out, like cities such as Houston (famous for its lack of zoning). San Francisco is almost completely surrounded by water. There is nowhere to go but up and tall buildings have entrenched political opposition. As a result of all these factors, housing units in San Francisco have grown much less than job numbers, resulting in a price squeeze.

Viewed just from a market economy aspect, rising prices can be regarded as a sign of success. Demand for a product—houses in California—is running way ahead of supply. Good for those who already own such houses, but not for those contemplating moving to California.

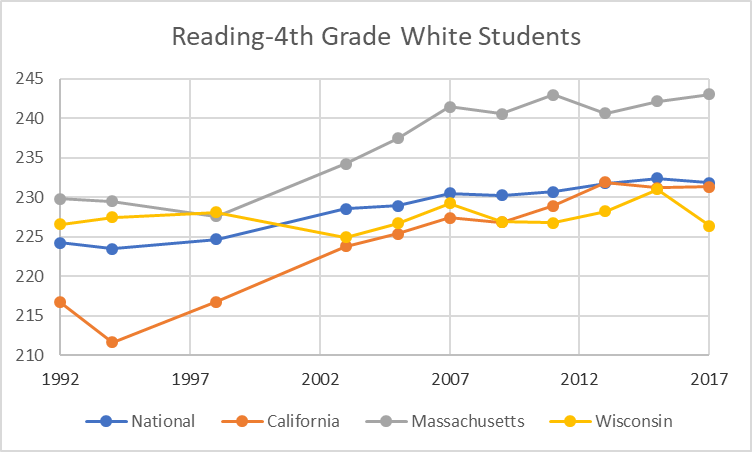

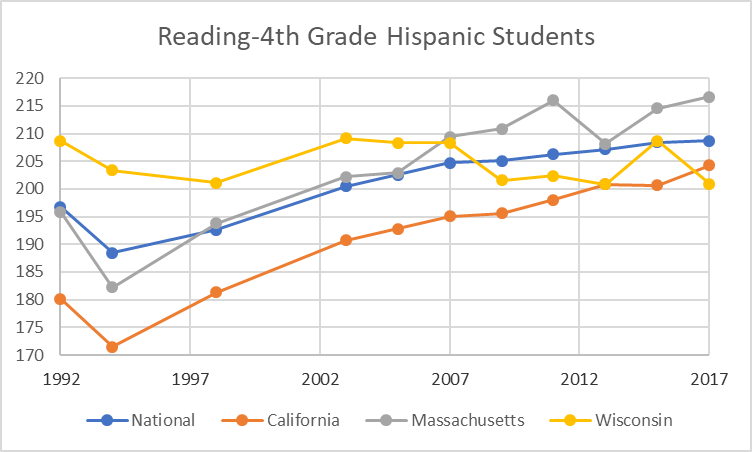

Another common criticism of California focuses on its educational outcomes. The next two graphs show scores for 4th grade reading on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) for two ethnic groups (results for math and 8th grade generally show the same patterns) and for three states and the US.

Massachusetts is widely regarded as showing what can be accomplished when all the major players get together to raise student achievement. Wisconsin shows what happens when a state starts out ahead but lets others pass it by.

California NAEP results earned their poor reputation in the past. More recently, however, it has been closing the gap with Wisconsin and the nation.

What are the lessons for Wisconsin of the California story? The first is political: Democrats should not expect demographic changes to rescue them or allow them to say goodbye to white working class voters.

The second is economic: increasingly, prosperity will flow to areas where people want to live. Therefore, to allow environmental degradation or to subsidize private industry by diverting resources from public services is likely to be counter-productive in the long run.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

I would prefer we aspire to be more like California, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Washington, and Oregon and less like Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, and West Virginia. Unfortunately, our right wing ideological governor Walker doesn’t see things that way. He looks to mirror failing Republican led states.

Hispanic Americans cannot be seen as a monolithic political block. Hispanics are more religious, more likely to be entrepreneur and own small business. Hispanics do not look down at women who choose motherhood as an occupation. Doubling the child tax credit benefits Hispanic Americans. Don’t be surprised in purple to red states that Trump gets 40 percent of the Hispanic vote. On another note, tax payers are leaving blue states and heading to red states.

Dump Walker 2018

Legalize cannabis

I hope not. If we think Milwaukee’s issues are bad where races are separated by arbitrary streets on our grid, California has put it’s affluent by the Ocean while it’s working classes live in desert valleys on the wrong side of mountain chains and caravan in each day in minivans to tend to the surfer/housing millionaires.

Massachusetts is a far better model; parochialism, a risk-averse local government structure, continued investments into universal institutions that create social capital to raise everyone up: schools, libraries, museums, philanthropies, etc. It hasn’t gone down the rabbit hole of trying to bribe businesses. It’s invested into active and mass transit alternatives so that it’s downtown’s aren’t giant wastelands of parking lots & garages. Turns out, folks like that about a place.

If we want to get serious, we need to fight for Milwaukee County political autonomy. If we could make our own decisions instead of being forced into ideas and concepts that don’t fit an urban environment we could really thrive. Milwaukee (and Madison for that matter) are substantially different beasts that the rest of this state, yet we’re treated as if concepts that work in 2,000 population towns are equally workable here. If we made our own decisions and used our own money, this county could really take off.

Not sure how we do it, but I’m in the second we get it rolling.

I lived in San Francisco for 16 years between 1998 and 2014. California is a very large, complex economy and ecosystem. There are some distinctions that can be made between north and south, coastal and inland, but even those breakdown quickly when considering the details many moving parts that make California thrive overall, despite many challenges.

In general, I believe California has thrived because of the broad valuing of openness, diversity, creativity and entrepreneurship.

One of the most fascinating things I’ve read in recent weeks is this piece in May 15th Crain’s Chicago Business, “The Day After Chicago Doesn’t Get HQ2.”

http://www.chicagobusiness.com/article/20180315/OPINION/180319930/the-day-after-the-day-chicago-doesnt-get-hq2

I’m not sure if you can read it without subscribing, but it cites a new book, Troublemakers: Silicon Valley’s Coming of Age, by Leslie Berlin. I’ve copied belowjust a portion of the piece, including some content directly from the book, that is spot on in understanding the values, attitudes and opportunities that came to bear in creating California’s current technological and economic dominance.

Two things stick out for me: Federally-funded research and, generous patent licensing.

***

This story of the Bay Area reaches back decades, and is illuminated by a new book, “Troublemakers: Silicon Valley’s Coming of Age,” by Leslie Berlin, recounting the formative years of biotechnology, microprocessors, video gaming, software, and modern venture capital — industries born and made in Silicon Valley in the from 1968 into the early 1980s.

I have heard many times of the need to spread “Silicon Valley juju” through Chicago — using precisely that term, strangely — yet in analyzing the region’s history, it appears Silicon Valley grew not out of “juju” but out of a robust channel of federal grant money, a willingness to work collaboratively across institutions, licensing of university-supported inventions to entrepreneurs, engineered partnerships that married engineers like Steve Wozniak with more seasoned business executives like Mike Markkula, and an ability to quickly test concepts.

As has been recounted by author Steve Blank, the foundation of Silicon Valley was built with federal money, sent to engineers at Stanford Research Park to build communications platforms to fight the Soviet Union. Engineering students were encouraged to take their inventions and start new companies; two students, Bill Hewlett and David Packard, did just that.

Berlin picks up the story of what came next, exploring the path between the post-War research projects and the explosive startup growth that followed.

“Troublemakers” unearths the story of Niels Reimers at Stanford, the founder of Stanford’s Office of Technology Licensing. Reimers supported the formative years of Silicon Valley by crafting licensing agreements that offered one-third of the royalties to the inventors — far more than MIT and Caltech, which typically only offered the inventor between 12 and 15 percent — and dramatically increasing the volume of Stanford-supported inventions commercialized through startups.

Reimers’ methods raised the objections of Stanford University’s president, who feared losing licensing revenue from corporate donors to the University.

Those concerns were unfounded. For the patent for recombinant DNA — a patent that was a collaboration between Stanford and University of California researchers, and is considered the foundational patent that led to the modern biotech industry — trucks lined up to deliver license applications, and both universities received hundreds of millions of dollars from the patent.

One startup that licensed the patent: Genentech Inc., which three decades later was acquired for $47 billion.

This is the kind of collaboration across institutions and free licensing of inventions to entrepreneurs that needs to be replicated in Chicago. And then we need to build these new products here. Again, the Bay Area provides a guide.

To test and build new products, Silicon Valley’s pioneers worked with local contract manufacturers (nothing offshore) to perfect designs of disk drives, printers, and consumer electronics: Atari built their gaming systems with Selectron, Hewlett and Packard their semiconductors with Weitek, and Sun Microsystems with Flextronics.

The Bay Area became not just a place but a laboratory. The founders of Atari, Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney, would prototype their first game, Pong, at Andy Capp’s Tavern in Sunnyvale, California. They knew they had a winner days later when they found the machine filled with quarters. Within weeks patrons would line up at 9 a.m. to play Pong.

The degree of openness in the Bay Area extended beyond the universities. For engineers in Silicon Valley in the formative 1960s and ’70s, commitments were made to fields of research and engineering, and to the cause of advancing technology, not to a particular firm.

Milwaukee needs a good head tax on downtown employers ($500), as they ramp up more city taxes in Seattle, so we can combat homelessness in Milwaukee. Northwestern Mutual, would be a good example of a company that has so much wealth and than they receive a corporate tax under Trump. Boston store will be missed a lot of heads no longer potentially taxed.

California and SF in particular, have had astronomical housing costs for decades and it has little to do with geography. Like New York City, San Francisco has always been a huge advocate of rent control. It is debatable which can destroy a city more efficiently, rent control or carpet bombing. Then they have this fetish for leaving all undeveloped land, undeveloped. They prevented the abandoned Santa Anita race track from being developed into housing, just as they did with The Presidio. A 1,500 square foot home in Palo Alto will set you back about $1 million. In Houston, it would be under $150,000.

WHY would anyone want to follow in racist SF footsteps? With only 5.1% blacks (15.1% nationally), most stuffed in one neighborhood, SF with its $2M 800 sq. ‘ homes proves….they have high cost to keep blacks out! OR…if NOT…why then does the City have more low income housing, OR forced rent controls? Clearly unlike say Milwaukee that is 40% black, 40% white, & 20% other…they can claim it to be racially bias instead!