Read an excerpt from new book centered on Milwaukee musician Klassik

Ahead of his Summer Solstice performance and Juneteenth, travel back to the summer of 2020 and the creation of his song “Black Holiday.”

MILWAUKEE – On Saturday, June 18, Kellen “Klassik” Abston will headline the Kenilworth Stage at Summer Solstice. The East Side street festival returns after a two-year pandemic-induced hiatus. Klassik’s performance will fall on the eve of Juneteenth, which commemorates the end of chattel slavery in the United States.

On Juneteenth 2021, Klassik released the song “Black Holiday”. The track was forged in the fire that was the summer of 2020. That June, Kellen and I began meeting for a series of interviews that I planned to turn into a profile. Prior to the pandemic and the protests, Kellen started to open up about his father’s murder and his journey recovering from trauma and substance abuse.

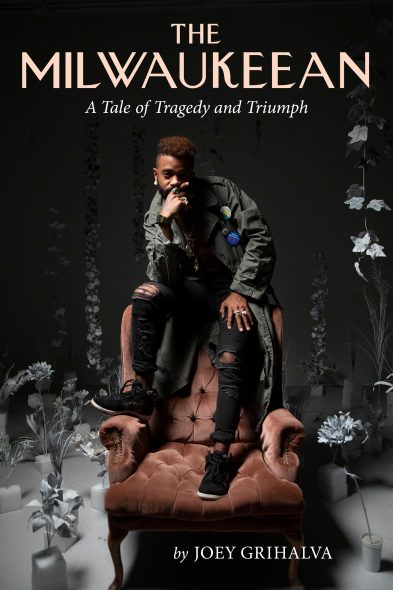

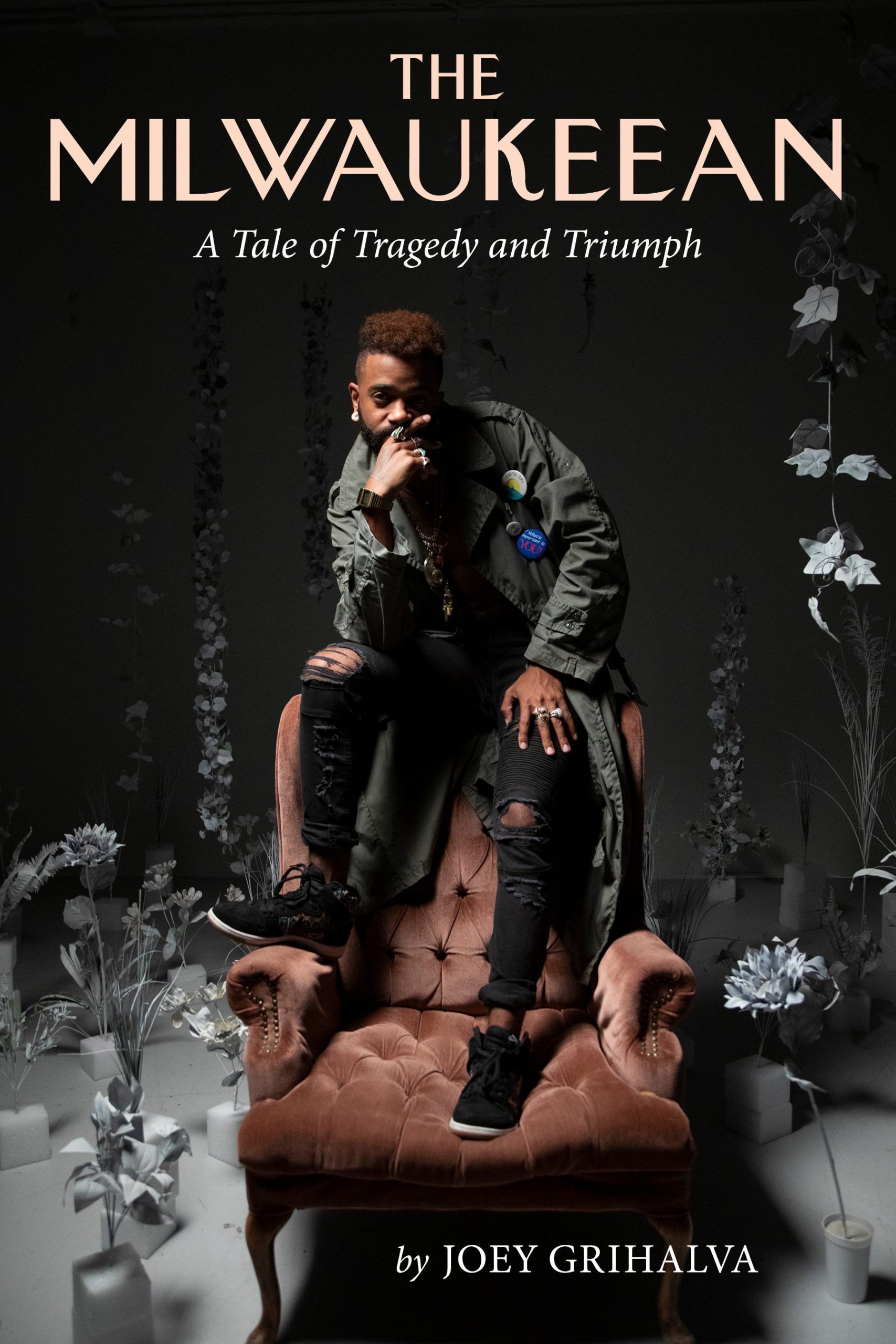

As the pandemic pressed on, the project snowballed into something grander than a simple biographical account of Kellen’s life and career. The result is my new book, The Milwaukeean: A Tale of Tragedy and Triumph, now available online, at Boswell Book Company, and at the Urban Milwaukee Store.

In addition to interviewing Kellen, I spoke with twenty additional people: family, friends, and professionals who deal with trauma, therapy, gun violence, and addiction. The book explores those issues, plus the creative process, spirituality, racism in America, police brutality, local music, and being an independent artist in Milwaukee.

The excerpt below captures some of that energy from June 2020.

—————

KELLEN AND I FIRST OFFICIALLY sat down for this book on the afternoon of Saturday, June 13, 2020. We had discussed meeting earlier, but we were both caught up in the emotional energy and activism following George Floyd’s death. We had recently marched in racial justice protests when we met at the duplex he and Jackie rent in Washington Heights. We spoke in their semi-finished attic, with the windows open, wearing masks. The attic is his latest in a series of home studio spaces. As soon as we sit down, he plays a song he was working on before I arrived. Performing the vocals live he sings, “Ask me if I think it’s justified, all my people trying to touch the sky. Everyday a Black holiday, gotta celebrate just to be alive. I can’t watch another life become a martyr, it’s getting harder to trust the other side. Ain’t that a trip? Because there ain’t no sides. Either you is or you ain’t down to ride.”

“This is my version of protest music,” he says as the track fades out.

A little over a year later, he would release that song — “Black Holiday” — on Juneteenth 2021.

For the interview, I prepared over a dozen questions, but only asked one: “How are you feeling right now, on the eve of Juneteenth, with everything that’s going on, plus a pandemic on top?” We talked for two and a half hours straight. He was calm and thoughtful, noting that it was the first week in some time that he hadn’t experienced multiple anxiety or panic attacks. A week prior, his computer crashed before a livestream for Rock the Green, which devastated him.

At the beginning of May, Kellen released a four-track EP entitled Klass Notes. At the end of the month, he performed an emotionally charged livestream for Nō Studios, a multi-purpose creative space founded by John Ridley, a Milwaukee native and the Oscar-winning writer of 12 Years a Slave. When he performed the Nō Studios livestream, George Floyd had only been dead for five days. In the video, Kellen wears a black and white “MILWAUKEE” hoodie with a black and white knit hat displaying the words “IN NOTHING WE TRUST.” Behind him is a black and white American flag hung upside down, which he addresses at the beginning of the stream.

“This country is definitively in a state of distress. Save our ship, it’s sinking. It’s been sinking for decades. What happened to George Floyd is what happened to Eric Garner is what happened to Dontre Hamilton is what happened to Philando Castile is what happened to Sandra Bland. The list is way too long.

“I know that there are folks out there right now on the streets having their voices heard. There’s a lot of talk about what’s wrong and what’s right. I want my people to be safe and I want a change. And I think that we all feel that way,” he says as his voice begins to crack.

“I’m going to try my best, but this is probably one of the hardest performances that I’ve had. I can hear the helicopters above me and outside. I know people…” Kellen cuts himself off and takes a pause. Before launching into the music he says, “This is for my people, this is for George Floyd. This is for some actual justice, please.”

As we talk, the flag still hanging behind him, I can sense that he is inspired by the moment. He is moved by how Jackie has become activated. And he is encouraged that a critical mass of Americans appear to be acknowledging that perhaps racism is scarier than Covid-19.

“The collective consciousness is changing. We’re saying that we’re not ignorant to this anymore, which is what has allowed this beast of racism to survive. That feigned ignorance, or blissful ignorance, or willful ignorance. More people are coming around from that. Even in the midst of not knowing if it’s okay to do this or do that, we’re saying that this is more important. That’s encouraging and my hope is that it will continue. Because that’s the downfall, to repeat history, as we so often do.”

“I remember gathering at Chauntee’s house and everyone feeling like, ‘What the fuck do we do?’ That was one of the first times where I felt pulled artistically, in terms of feeling a responsibility with my platform. It heightened this desire to wield it, almost like a weapon, for good.”

The weekend of the inaugural Strange Fruit Festival coincided with the second Eaux Claires Festival, which I was covering for the Wisconsin Gazette and 88Nine. Kellen was in New York City during the first two nights of Strange Fruit. That Friday he performed in NYC for the first time as Klassik. He was on a bill with my friend Bassey Etim’s band Minus Pedro at a venue in Brooklyn.

That Saturday afternoon, Milwaukee police shot and killed Syville Smith in the Sherman Park neighborhood near my childhood home. The incident sparked riots that culminated in the burning of a gas station, a bank, and a beauty supply store. Groups of young Black people clashed with police, throwing rocks and debris at them. By the next morning, images of the burning gas station could be seen on international news.

I learned of the Sherman Park riots while standing in a field at Eaux Claires awaiting Francis and the Lights’ festival closing set. There was a rumor that Chance the Rapper, who had performed at the nearby Summer Set festival the night before, was going to appear. Sure enough, Chance triumphantly took the stage and performed alongside his friend Francis, but not before I started receiving texts from friends back home asking if my parents were safe.

At that moment, Kellen was in Manhattan at a performance of Shakespeare in the Park. I spoke with him later that week for the Wisconsin Gazette.

“There was a sense of urgency coupled with the motivation that I already had from being in New York City. We didn’t know at that point if I was going to be back in time to play with Foreign Goods, but then more than ever I was determined to be at that show on Sunday night at Cactus.”

“We could smell the smoke and hear the sirens from Company Brewing,” recalls David Ravel, who helped out with the logistics of staging Strange Fruit. “It became something that everyone was responding to in real time. It was very, very intense. Then people came to Cactus the next night with Sherman Park definitely on their minds. That was the night that I heard Rory for the first time. It was magnificent.”

“Everybody came with their A-game,” Kellen told me back in 2016. “The performances were top-notch. Rory killed it. He headlined that Sunday night and had a phenomenal set. I gotta give it up to Chauntee and Jay for putting that together. It was such an amazing event. You could tell everybody was there for the betterment of the community in whatever small or large way they could. And it was just crazy timing that we had this festival amid the madness that ensued.”

When we spoke in the attic three weeks after George Floyd was killed, Kellen said there was talk of revisiting Strange Fruit, which had two more iterations in 2017 and 2018. He mentioned a possible website with interviews and performances, that would go live sometime closer to the presidential election. It never got off the ground, but Kellen shared a manifesto he was working on for a potential relaunch of the festival.

“For four hundred and one years, Black people have fought to just be. To matter. For the American Dream we were forced to adhere to, but consistently left out of. Generations of wealth and opportunity were birthed from our sweating, bloody bodies. From sub-human, to fractionally human, to ‘separate but equal,’ to redlining and every other legal manipulation of our freedoms over the course of American History, it has been made clear where the power lies, and what the powers that be will do to keep it distributed as such.

“Strange Fruit, since its inception in 2016, has always tasked itself with bringing the most thoughtful, intentional, and passionate artists to the forefront of these discussions in order to pierce through the revisionists history and ensure the veracity of the New American History, essential to the foundation and framework of Black liberation. Assembling a collective of interdisciplinary, intergenerational, and multi-genre artists, Strange Fruit recognizes the power of vulnerable and emotive art to amplify the Black Reality, and highlight a path towards true equality and justice.”

NOTE: This press release was submitted to Urban Milwaukee and was not written by an Urban Milwaukee writer. While it is believed to be reliable, Urban Milwaukee does not guarantee its accuracy or completeness.

Mentioned in This Press Release

Recent Press Releases by Joey Grihalva

Read an excerpt from new book centered on Milwaukee musician Klassik

Jun 15th, 2022 by Joey GrihalvaAhead of his Summer Solstice performance and Juneteenth, travel back to the summer of 2020 and the creation of his song “Black Holiday.”