Many Communities Have Unsafe Drinking Water

An estimated 800,000 state residents consume contaminated well water.

Frank Michna buys bottled water for drinking and cooking in his Caledonia home because of high levels of molybdenum and boron in his well. Photo by Cole Monka of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

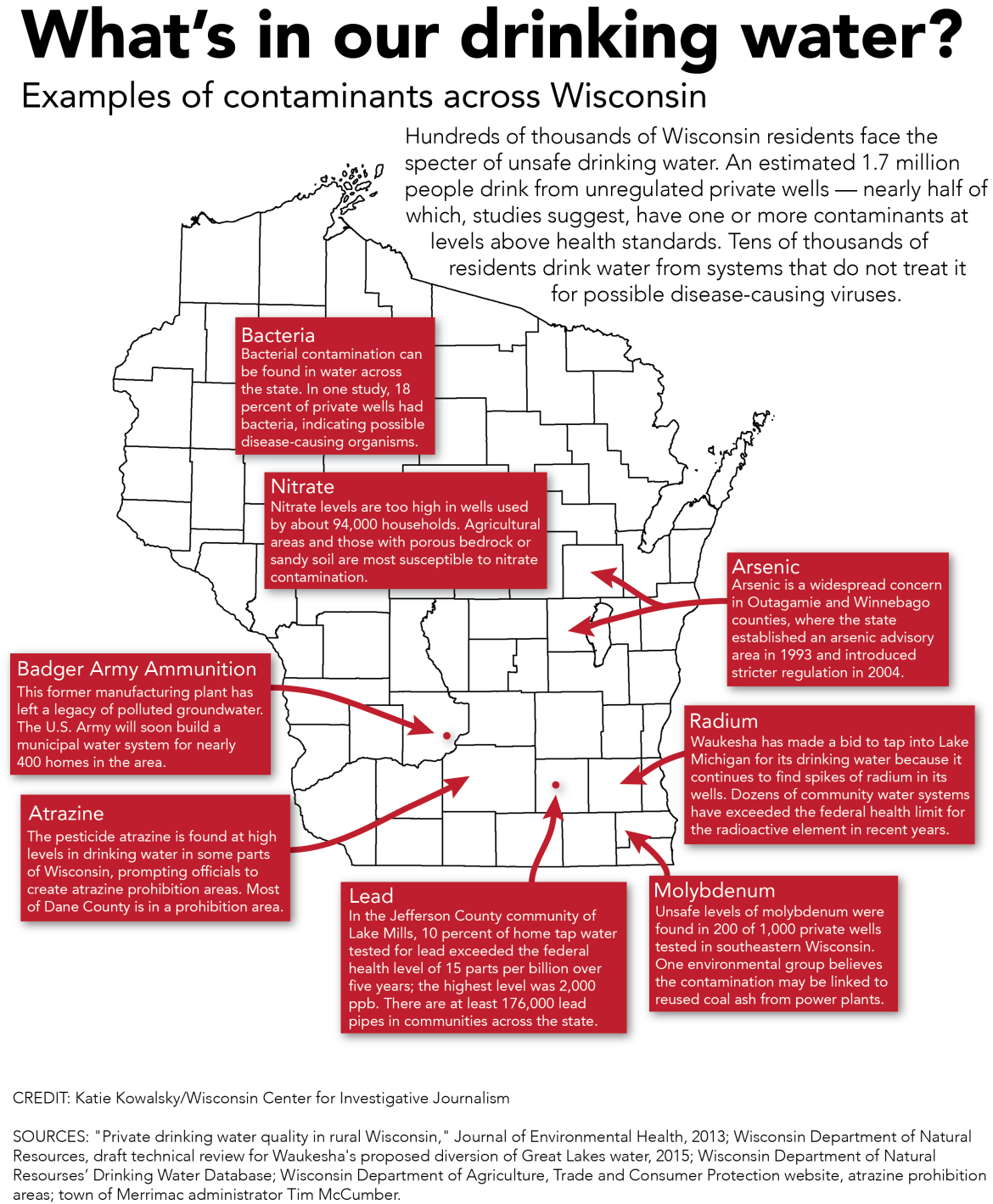

In this place, hundreds of thousands of people face the specter of drinking water from wells that is unsafe, tainted by one or more contaminants such as arsenic or nitrate.

In this place, for some, even brushing their teeth or cooking a meal can give pause because of the risk of lead from aging water pipes. The dangers to children, often more susceptible to pollutants than adults, and even pets and livestock, cause nagging fear.

Surely, this place — on a planet where the United Nations estimates 783 million people lack access to safe drinking water — lies in a distant nation.

But this polluted water is right here. In many parts of Wisconsin. In a state whose very name evokes the image of lakes and rivers and clean, cool, abundant water.

Lynda Cochart’s water from her private well was so poisoned by salmonella, nitrate, E. coli and manure-borne viruses that one researcher compared the results from her Kewaunee County farm to contamination in a Third World country. She suspects the problem is related to the county’s proliferation of large livestock operations, although testing did not pinpoint the source.

“Realize that we can’t drink, brush our teeth, wash dishes, wash food; we can’t use our water,” Cochart wrote in a letter last year to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, seeking intervention in the county’s drinking water problems.

“Our water is on our mind all the time. If drinking it doesn’t kill us, the stress of having it on our mind and worrying about it all the time will.”

Hundreds of thousands of Wisconsin’s 5.8 million residents are at risk of consuming drinking water tainted with substances including lead, nitrate, disease-causing bacteria and viruses, naturally occurring heavy metals and other contaminants, the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism has found.

The problem persists, and in some areas is worsening, because of flawed agricultural practices, development patterns that damage water quality, geologic deposits of harmful chemicals, porous karst and sand landscapes, lack of regulation of the private wells serving an estimated 1.7 million people, and breakdowns in state and federal systems intended to safeguard water quality.

Studies show an increasing number of residents using private wells around the state are drinking unsafe levels of nitrate — most of it from fertilizer, manure or septic systems — which can be fatal to infants and has been linked to birth defects.

Tens of thousands of people living in homes in Milwaukee, Wausau and other cities with aging water pipes and fixtures may be exposed to lead, which can cause brain damage in children. Homes built before 1950 are likely to have lead pipes, according to the DNR. Those built before 1984 also could have lead in their fixtures or lead solder on pipes, the agency said.

The Center found that in many cases, residents are on their own when it comes to safeguarding their drinking water. Private well owners are not required to test their water, and only 16 percent do so annually, although 47 percent of private wells are estimated to be contaminated by one or more pollutants at levels above health standards. One-third of respondents to a 2008-09 state health survey said they had never tested their wells.

Even consumers of some municipal water should be wary. In 2009, after researchers found viruses in public water supplies, the state began requiring disinfection. In 2011, the Legislature rescinded the rule, with its sponsor, Rep. Erik Severson, R-Star Prairie, calling it “an unnecessary and financial bureaucratic burden.”

Kimberlee Wright, executive director of Midwest Environmental Advocates, a nonprofit environmental law firm, says Wisconsin lacks adequate regulation to protect drinking water. Photo by Stacy Harbaugh courtesy of Midwest Environmental Advocates.

In 2012, researchers definitively linked the presence of the viruses in 14 Wisconsin municipal water systems to acute gastrointestinal illness. More than 73,000 people use water provided by 60 municipal water systems that do not disinfect, according to DNR figures.

Last month, Doug and Sherryl Jones, of Spring Green, and Dave Marshall, a former Department of Natural Resources researcher from Barneveld who studied aquatic organisms, were among 16 Wisconsin residents who petitioned the EPA to revoke Wisconsin’s authority to issue pollution discharge permits under the Clean Water Act if the DNR does not correct deficiencies.

The discharge permits are a key mechanism by which Wisconsin limits pollutants, including manure from large farms, that reach the sources of Wisconsin’s drinking water. Both the Joneses and Marshall cited unsafe levels of nitrates in drinking water wells in the Lower Wisconsin River Valley.

Kimberlee Wright, executive director of Midwest Environmental Advocates, the Madison law firm representing the residents, said Wisconsin lacks an adequate regulatory program to protect water, including what flows from residents’ taps.

DNR spokesman Jim Dick countered that the DNR “takes its responsibility to protect Wisconsin’s waters seriously and does enforce the Clean Water Act. We are working within the confines of current state and federal laws and rules to do just that.” He declined to make any DNR officials available to discuss the Center’s findings.

Environmentalists are not the only critics of Wisconsin’s approach to safeguarding water.

Last year, an administrative law judge accused the DNR of “massive regulatory failure” for failing to prevent widespread contamination in the private wells used by Kewaunee County residents living near large dairy farms.

Judge Jeffrey Boldt, while granting a large farm’s permit to expand its herd beyond 4,000 cows, ordered the DNR to take several steps, including requiring Kinnard Farms to conduct off-site well testing and cap the number of cows based on “limits that are necessary to protect groundwater and surface waters.”

Dave Marshall, a former Department of Natural Resources scientist from Barneveld, holds upa sample from the Wisconsin River, which he said is polluted by nitrate. Some of his neighbors’ wells also are contaminated with unsafe levels of nitrate. Marshall is one of 16 Wisconsin residents who have filed a petition with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency asking for the state DNR’s authority to administer part of the Clean Water Act to be revoked if it does not correct deficiencies. Photo by Bridgit Bowden of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

As of October, the agency was refusing to comply with those two requirements, saying it lacked the legal authority to impose them.

In the absence of rigorous enforcement, the Center found, residents can begin safeguarding their water by using methods including having their private wells tested for contaminants common in their areas or using safer practices when it comes to using water from aging lead pipes. Filters and water conditioners also can remove some harmful elements from drinking water.

But environmental advocates say state and federal lawmakers and regulators must do more to ensure the safety of Wisconsin’s drinking water.

Residents “think the government is protecting their water,” Wright said. “It’s not.”

Article Continues - Pages: 1 2

Tainted Water

-

Fecal Microbes In 60% of Sampled Wells

Jun 12th, 2017 by Coburn Dukehart

Jun 12th, 2017 by Coburn Dukehart

-

State’s Failures On Lead Pipes

Jan 15th, 2017 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

Jan 15th, 2017 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

-

Lax Rules Expose Kids To Lead-Tainted Water

Dec 19th, 2016 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

Dec 19th, 2016 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

For the people who complain about Waukesha being required to cover water service for rural areas surrounding the city, this is why. Many rural well systems are at risk for contamination and thus the DNR is tasked with making sure everyone has a potential source to clean healthy water. It had nothing to do with water diversion and everything to do with this exact situation.

Maybe if we’d stop the widespread of those hell-on-Earth CAFO’s across the state, we’d see a huge decline all these chemicals- particularly arsenic, nitrate and an array of bacteria. These are poisoning our state and the health of individuals.