The Mighty Grand Avenue Viaduct

A bridge with arches larger and longer than any in America but an avenue 75 miles shorter than first planned.

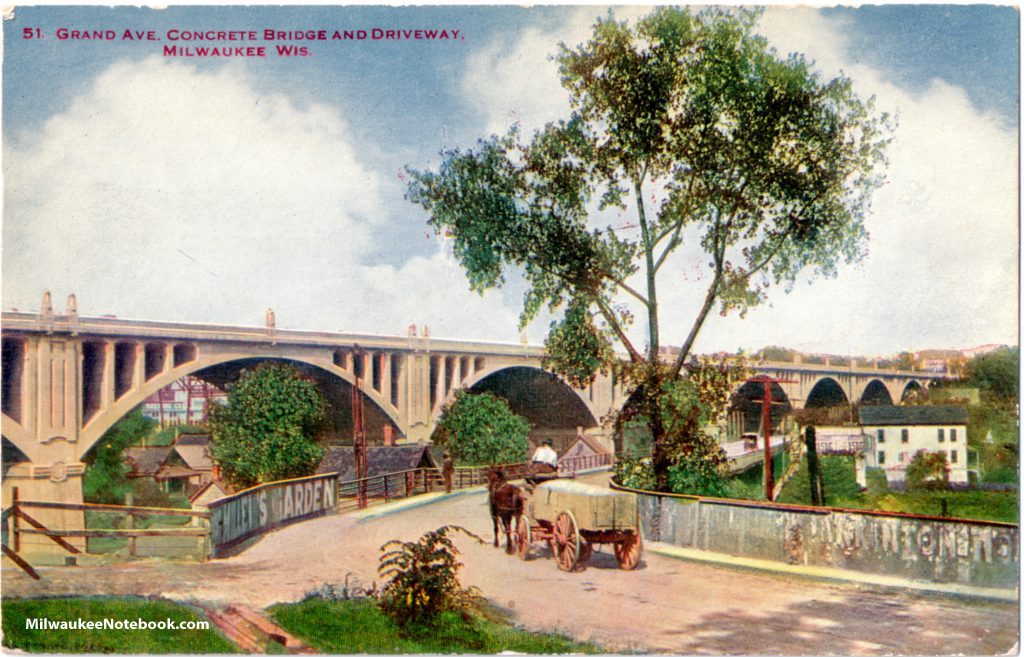

Horse-drawn carts like the one shown in this postcard view were common sights when the Grand Avenue viaduct was built in the early 1900s. Carl Swanson collection.

Wisconsin was in a mood to dream big in the years following the end of the Civil War. One idea involved extending Grand Avenue (today’s Wisconsin Avenue) from the shore of Lake Michigan all the way to Madison—creating an 80-mile-long boulevard lined the entire distance, they were certain, by elegant mansions and places of worship.

Before anything like that could happen, a suitably impressive way had to be found to carry Grand Avenue across the broad Menomonee River valley. So, after years of indecision and political infighting, Milwaukee set to work on a massive viaduct. Its construction sparked lawsuits, took far longer than expected, and cost much more than estimated.

Pretty much every Milwaukee road project ever, in other words.

But the Grand Avenue viaduct was also a triumph. Upon its completion in 1911, it was immediately regarded as one of the world’s most notable structures.

The idea became a reality largely through the efforts of a single Milwaukee County supervisor, Samuel Bell. The owner of a Milwaukee insurance company, Bell had served in the Union Army in the Civil War. Elected to the county board, Bell was named to the board’s highways and bridges committee.

Bell stepped in after an attempt to fund a viaduct across the Menomonee Valley at the west end of Grand Avenue failed in 1896. At that time, much of the land at the west end of the bridge was owned by real estate companies and it was not clear how the project would benefit the public. The proposal went nowhere.

Bell revived the measure back in 1899, only to have supervisors balk at the viaduct’s estimated cost of up to $190,000 (the equivalent of $5.8 million today).

In 1900, Bell introduced—for the third time—the proposal. By now all the west end lots had been sold to private individuals and Bell was in an optimistic mood. He told the Milwaukee Journal, “If the assessors do their duty, the county will have a material increase of revenue from this source of taxation … there will almost be a new city out there.”

He added, “This year (1900) it is before the board again. The land necessary to build the west end is assigned to the county. The members seem favorable to the proposition and it looks as if it would go through.”

In the same article, Bell noted the board was only on step one.

“What the board must do is this: First to decide that the building of the viaduct is to the best interests the county and that it should be built. A resolution to that effect is now before the board. Second, locate the viaduct. Third, to have a survey made of it. Fourth, secure the property by condemnation or purchase. Fifth, secure a profile plan and specifications for the work. Sixth, to advertise for bids and, seventh, to make the bond issue. All this has to be done by proper resolutions and it would take eight or nine meetings to get it though if a step were taken at each meeting.”

In a May 7, 1900 article headlined “Viaduct is Assured” the Journal reported Bell’s proposal had cleared the highways and bridges committee and would go before the full board where, the newspaper noted, no significant opposition was expected.

The next day Bell’s measure was blocked when a fellow supervisor introduced a resolution to take no action until the state legislature passed a law giving the county authority to “assess benefits and damages in the vicinity of the viaduct.”

Bell finally got the project off the ground in 1904 when county supervisors approved the project by a 26 to 12 vote. The proposal had been kicking around for eight years.

To find the best design for the proposed viaduct, the county sponsored a nationwide competition with a prize of $1,500 ($40,000 today). A New York engineer named Edwin Thacher was the winner for an art deco barrel-arch design based on concepts developed by Joseph Melan of Vienna. The Melan system relied on a core of steel I-beams shaped to form the arches and then encased in poured concrete.

In 1907, the county collected bids for the viaduct’s construction. A local firm, the Newton Engineering Co., was the low bidder at $372,000. To keep an eye on the project, the county hired Gustav Steinhagen, who, in 1892, had built the 2,085-foot-long Wells Street trolley viaduct, which crossed the Menomonee Valley a block north of the Grand Avenue viaduct site.

There was a local shortage of laborers at the time so Newton Engineering hired large numbers of African-Americans from Tennessee. The concrete was poured at night and these workers would tamp it down in unison, singing spirituals as they did so to keep their rhythm. This was something new for Milwaukeeans and they crowded around the bridge in the moonlight to listen.

“People would come from miles around,” Ralph Hayward, who worked on the viaduct, told the Milwaukee Journal in a 1950 interview. “All you could hear was the sound of singing.”

Behind the scenes, things were less harmonious. Just weeks after construction started, the contractor and Steinhagen were bickering. Steinhagen said the builders ignored his orders and had too few employees on the job while the Newton Company said Steinhagen was “arbitrary and unreasonable.”

After a year of this, the county had enough. The Newton contractors were dismissed and the company promptly filed a lawsuit against the county for unpaid work. A group of local builders banded together to form the National Engineering & Construction Co. and took over the project.

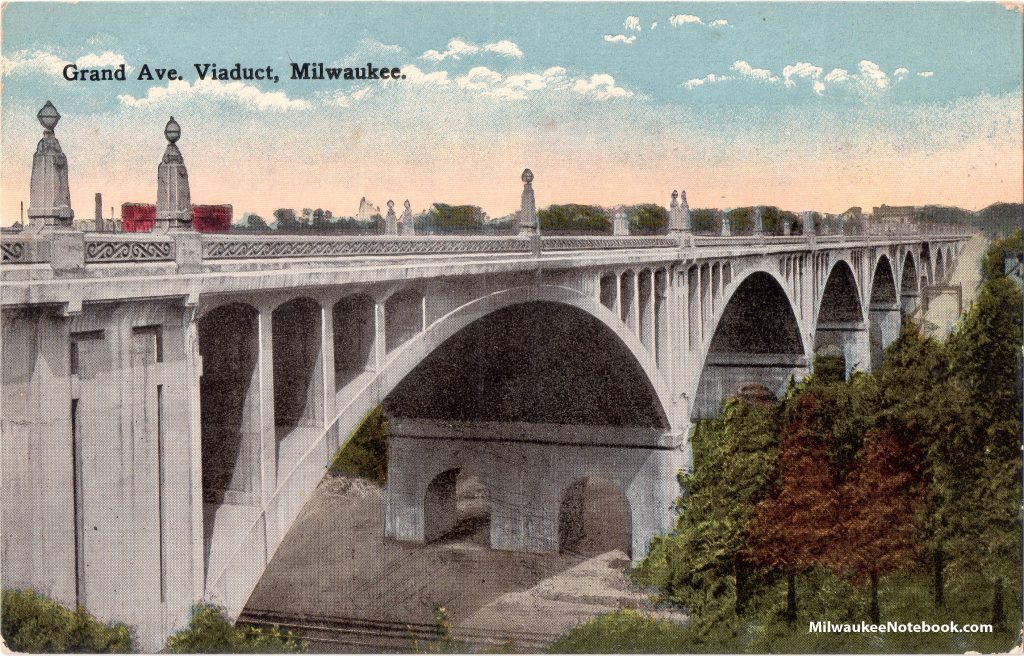

Three-hundred workers were soon hard at work turning 900 tons of steel and 55,000 barrels of cement into eight massive 145-foot-span arches, one 80-foot-arch, and one 60-foot arch together forming a graceful span 2,088 feet long, 80 feet high, and supporting a 67-foot-wide roadway.

On October 24, 1910, the contractors turned the bridge over to the county for final finishing work, which included the roadway approaches at both ends of the new bridge. Then they too filed suit against the county for extra work authorized by Steinhagen.

The final cost of the bridge totaled $614,475 ($14.4 million today), nearly double the original bid and three times higher than the $190,000 estimate that had so horrified the board in 1899.

To no one’s surprise, there were further delays. The county board even managed to put off casting a commemorative bronze tablet to be attached to the structure. The proposed tablet included Steinhagen’s name and the names of the members of the county board that had originally approved the project.

“Well, let’s see,” the Milwaukee Sentinel quoted one supervisor saying, “shouldn’t the names of the new board be on that tablet instead of the old?” Most of the committee, the Sentinel noted, believed he was right “especially those who were not members of the old board.” Supervisors decided to delay having the plaque made while they considered the question.

In an April 29, 1911 editorial note, the Milwaukee Sentinel acidly remarked, “Possibly the new Grand Avenue viaduct will be open to the public by the time it is necessary to build a new one.”

Milwaukee residents were also feeling impatient. On a fine Sunday in May 1911 hundreds of people descended on the viaduct, ignored warning signs and climbed fences in order to walk across the valley on the new bridge.

Finally, on July 4, 1911, the viaduct was declared open. Horses and buggies had been common when the project was first discussed but when it opened fifteen years later, automobiles by the hundreds crossed the new span.

Milwaukee residents could finally take stock of what had been accomplished and, possibly to their surprise, found they had created a landmark.

“The Grand Avenue viaduct is considered by foremost engineers to be the finest in America, both in construction and from an artistic standpoint,” the Sentinel noted. “The arches are the largest and longest of all bridges in America and only two bridges in Europe exceed the Milwaukee bridge in length of arch spans.”

The concrete bridge included a scroll design balustrade and Art Deco streetlights. Two streetlights were located above each pier, with one above the arch’s crown. Carl Swanson collection.

The cement contractor for the project, the Marquette Cement Manufacturing Company of LaSalle, Illinois proudly printed a booklet describing the viaduct as, “a feat of engineering that will not be eclipsed in either beauty or size for many years to come.”

A national trade magazine, Rock Products, printed a cover story in its April 22, 1911 issue, writing, “From all over the country expert engineers and builders were attracted to the sight of the great achievement to witness the building of the great structure and study the methods employed in its construction. This viaduct is by far the greatest concrete bridge in the world, its mighty arches towering high in the air and the giant supporting piers present a spectacle which has to be seen to be appreciated.”

The plots of land west of the viaduct quickly became a desirable residential area, which considerably bolstered the development of Wauwatosa. Supervisor Bell, who visited the viaduct site nearly every day during the years of its construction, had predicted the outcome and must have been pleased to see his persistence pay off.

In the end, the dreamed-of boulevard to Madison got no farther than the west side of the Menomonee Valley.

The present Wisconsin Avenue viaduct was built in 1993 to replace the original bridge. The modern bridge incorporates arches designed to recall the appearance of the earlier structure. Carl Swanson photo

Carl Swanson is the author of the book Lost Milwaukee from The History Press, available from book stores or online.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Lost Milwaukee

-

When Police Handed Out Courtesy Cards

Jul 14th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

Jul 14th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

-

Riverwest Had World’s Largest Color Printing Press

Jun 11th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

Jun 11th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

-

The Man Who Made Milwaukee

Mar 9th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

Mar 9th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

When and why was it demolished?