Why The MPS Referendum Is Needed

The data shows MPS trails other metro area districts in per-pupil spending.

In a recent column, Bruce Murphy reported on a poll that found “surprising strength” in support for a upcoming referendum — on the April ballot — that would raise the cap on spending by Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS). Murphy reported that the poll, which was commissioned by MPS, found over 70 percent agreeing that MPS needed more funding, with between 60 percent and 64 percent supporting an increase in taxes.

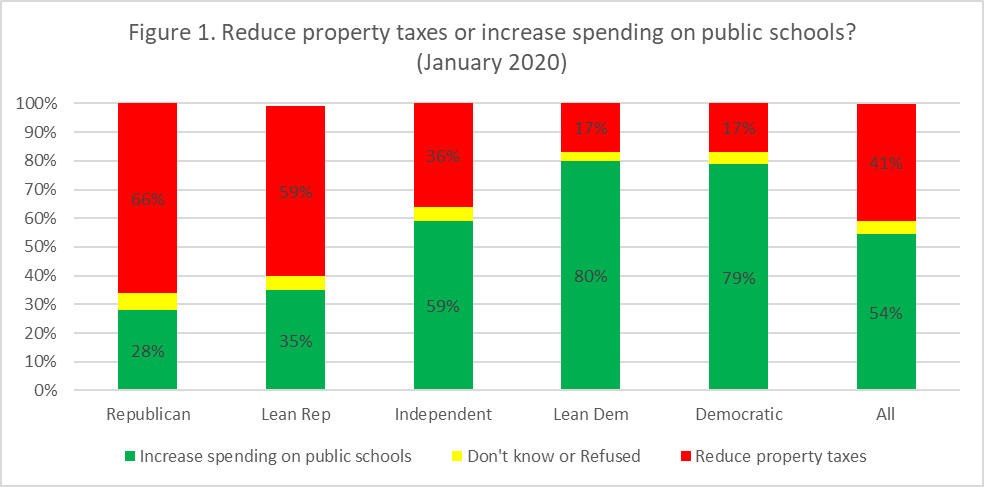

This result is no anomaly. Between 2013 and this January, the Marquette Law School poll included the following question 11 times: “Which is more important to you: reduce property taxes or increase spending on public schools?” Figure 1 shows the results from January of this year. (In this and the following graphs, I borrowed the traffic light color scheme, where green reflects the number of people prioritizing education funding, red for those favoring lower taxes, and yellow for those not offering an opinion.

Support for school spending is one issue that shows a distinct partisan split. Although a majority of Wisconsin voters favor more education spending, a majority of Republicans (and independents who lean Republican) do not. That said, support for school spending has grown by roughly 10 percent among both Republicans and Democrats over the seven years the MU poll has asked this question.

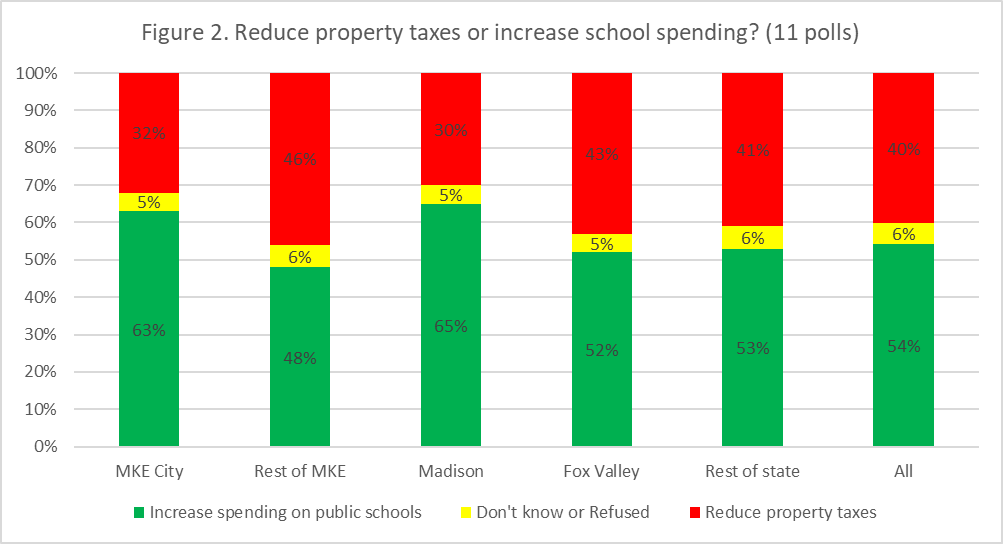

But the fate of the MPS referendum depends on sentiment among Milwaukee voters, typically about 9 percent of the statewide total. Figure 2 shows opinion in the city of Milwaukee, the Milwaukee metro area outside the city, the Madison area, the Appleton and Green Bay area, and the rest of Wisconsin. This is based on all 11 times the question was asked.

Milwaukee voters prioritize education funding over taxes by a two-to-one margin. This is consistent with the results of the poll commissioned by MPS.

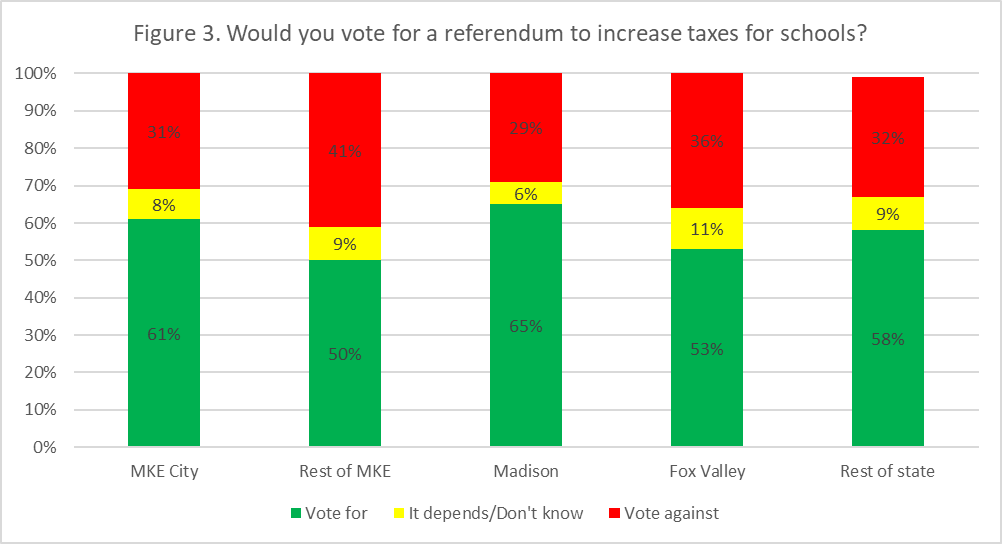

In January of last year and February of this year, the Marquette poll asked, “If your local school board proposed a referendum to increase taxes for schools would you be more inclined to vote for or to vote against that referendum?” When put this way, support for school spending increased. It appears that a referendum for increased education spending would enjoy majority support almost everywhere in Wisconsin.

Since the early 1990s, Wisconsin’s school funding has revolved around two “legs.” The first, the revenue cap, is the subject of the referendum. Each year, each district’s allowable spending per student, its “revenue limit,” is calculated by taking its previous year’s revenue limit and, in most years, adding an allowable increase. The second leg (more about that later) was a state formula for aid to school districts. (A third leg—a limitation on pay and benefit increases–was eliminated years ago.)

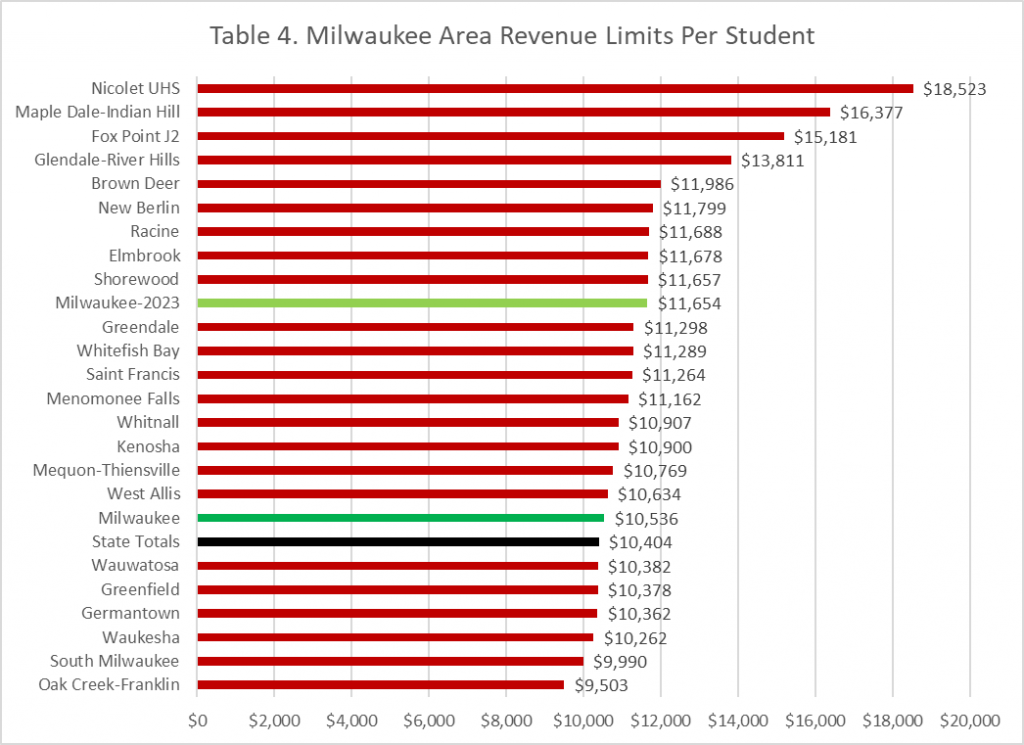

Figure 4 shows the 2018 revenue limits for Milwaukee Public Schools (in dark green) and many of its neighboring school districts (in red). It also shows the average Wisconsin district in black. MPS is very close to the state average. However, it is at the low end of districts in the Milwaukee metropolitan area. Among other implications, this likely puts MPS at a competitive disadvantage in attracting teachers.

As Nicolet and its feeder schools reflect, when the revenue limits were introduced, they locked in previously high-spending schools. Milwaukee, by contrast, was locked into its previous limit at the state average and on the low end below most suburban schools.

This is reflected in Figure 5, which plots the revenue limit since it was introduced. It charts the revenue limits for Milwaukee, Wisconsin as a whole, and two suburbs—Wauwatosa and Shorewood. Milwaukee’s limit closely tracks the state average. It is clear from Figure 5 (below) that MPS has mainly budgeted, in most years, at the revenue limit. By contrast, it appears that Wauwatosa and Shorewood have not used their whole revenue limits.

When fully phased in over four years, the referendum would result in a 10 percent increase in the MPS budget, shown with the light green bar in Figure 4 (above). It would result in MPS moving upward from the low end of the Milwaukee region to somewhere between Shorewood and Greendale. Note that this comparison is at best an approximate one—in the next four years, all revenue limits will likely change by an unknown amount depending on actions by the legislature and governor.

The drop in revenue limits that Figure 5 shows between 2010 and 2011 reflects cuts in education spending introduced by Gov. Scott Walker through Act 10. I was surprised to see that Wauwatosa and Shorewood seem to have gone beyond the cuts mandated by the state.

The second leg of the school finance “stool” introduced in 1993 was a formula used to determine the share of a district’s spending coming from state aid and the share from local property taxes. It starts by calculating the ratio of the total taxable property value in a district divided by the number of students. The smaller this ratio, the larger the amount covered by state aid. The aim is to equalize the tax burden between property-rich and property-poor school districts.

Total state aid was set originally to pay two-thirds of statewide educational costs. With the Great Recession, the state share was cut. Governor Tony Evers has proposed restoring the two-thirds commitment but has not been able to gain the support of the Legislature. In recent years this formula results in Milwaukee property taxpayers paying around one-third of the cost of MPS.

It is unrealistic to expect the additional funds from the referendum to solve all MPS’ problems. Many MPS students face enormous problems outside school that interfere with their ability to succeed in school. While some Milwaukee schools—charter, choice, and traditional—seem to have figured out how to help their students overcome those challenges, there seems to be no strategy to identify and replicate the factors for their success. Ironically, MPS, whose business is learning, is not a learning organization.

MPS’ handling of the poll that Murphy mentions is symptomatic of this culture. Why didn’t it simply place the results on its website? Instead, the report was released in response to an open records request from attorney Dan Adams. So far as I can tell, MPS has still not publicly posted the poll results. This lack of transparency reflects a bigger cultural problem with the MPS administration. It is very hard to improve if one is reluctant to be openly share data.

While recognizing the referendum is no panacea for MPS’ challenges, I believe its passage is desirable. The suggested uses for the additional funds–ranging from expanding early childhood education to stabilizing the workforce—benefit Milwaukee. Conversely, the referendum’s defeat would have a very negative effect on morale in MPS.

Finally, it is worth noting that the referendum is not advisory. Unlike those asking voters to support a sales tax for, say, parks or public transportation, it will take effect whether or not the state Legislature approves. Thus, its passage is an assertion of local control in the face of a Legislature intent on taking local powers away.

More about the 2020 MPS Referendum

- Near-Record Year for School Referendums - Madeline Fox - Apr 15th, 2020

- Data Wonk: Why The MPS Referendum Is Needed - Bruce Thompson - Mar 11th, 2020

- Op Ed: Why I’m Canvassing for MPS - Chloe Smith - Feb 26th, 2020

- Murphy’s Law: Poll Shows Surprising Support for MPS - Bruce Murphy - Feb 12th, 2020

- The Educator: The Rationale for MPS Referendum - Terry Falk - Jan 14th, 2020

- Milwaukee Board of School Directors Votes to go to Referendum - Milwaukee Public Schools - Dec 20th, 2019

- Questions for Milwaukee teachers’ union on poll results - Milwaukee Works, Inc. - Dec 12th, 2019

- Op Ed: Say Yes To MPS Referendum - Julie Rowley - Dec 5th, 2019

- Data Wonk: Would MPS Referendum Pass? Should it? - Bruce Thompson - Aug 7th, 2019

Read more about 2020 MPS Referendum here

Data Wonk

-

Why Absentee Ballot Drop Boxes Are Now Legal

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Does anybody honestly think that just blindly throwing money at M.P.S. will improve educational outcomes? After viewing the most recent report cards for milwaukee schools it would appear the best way to improve outcomes would be to close down M.P.S. and let all of the kids use vouchers to attend private schools. This would improve outcomes and reduce costs by almost 35 percent! Our youth deserve better and thats what we call a win win.

Parental involvement is the key factor in a student’s education. A parent may choose a voucher school or a highly rated public school AND ALSO NOT TOLERATE TRUANCY. Good education results.

Non-involved parents, by default, tolerate truancy which hurts their child and others in a class with high truancy. Quality of education suffers for all students in the class.

Spend the money to train people to intervene and help parents become better parents.

Repeated for emphasis:

Spend the money to train people to intervene and help parents become better parents.