Does Manufacturing Tax Credit Matter?

Evers would scrap tax break passed by Walker and Republicans. Will that help or hurt?

In his campaign to become Wisconsin’s next governor, Tony Evers has proposed doing away with Wisconsin’s Manufacturing and Agriculture Tax Credit. Doing so would free up about $300 million in annual state spending that could be spent on other priorities. Would repeal negatively affect Wisconsin’s manufacturing employment?

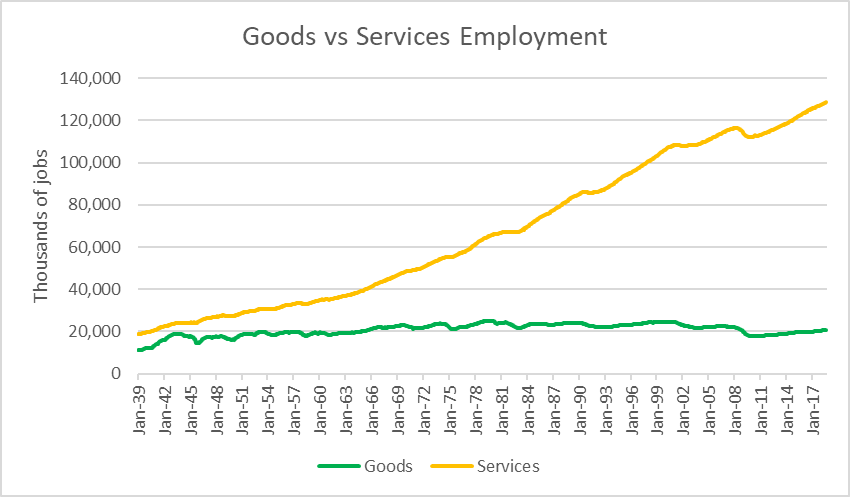

It’s no secret that manufacturing jobs have seen a steady decrease in their relative importance in the US. This is part of a long-term trend. As the next chart shows, at the end of the Second World War, about equal numbers of people were working in services and in producing things—about 20 million in each. Today service employment has grown to around 130 million, while goods producers have been stuck at 20 million for the past 80 years.

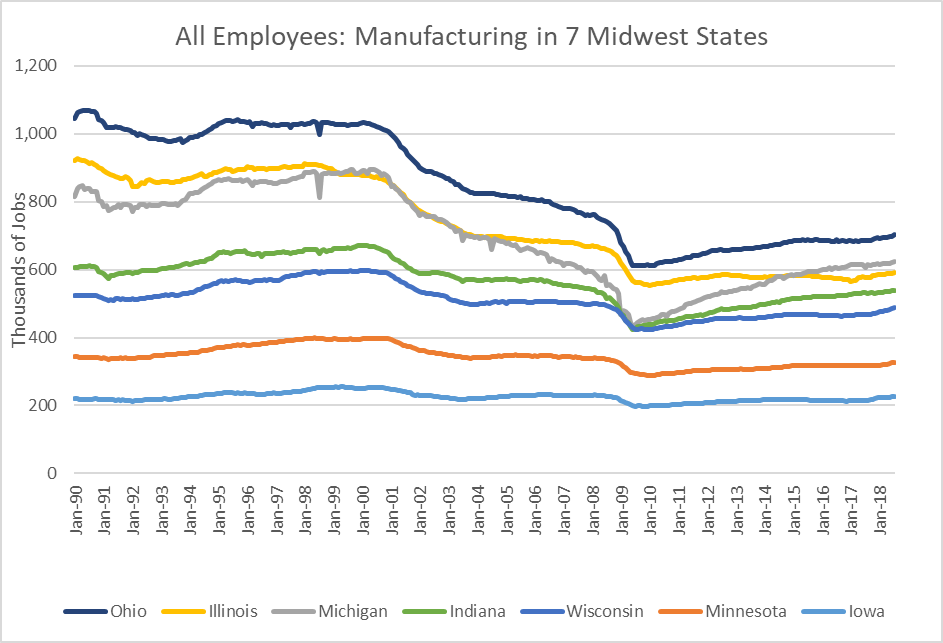

There has also been a shift southward in the remaining manufacturing jobs, again a long-term trend that started with the textile industry’s move from New England to the South and continues today, with new auto plants being built in Alabama and Tennessee rather than Michigan or Wisconsin.

Shown below are manufacturing jobs since 1990 in Wisconsin and six of its neighbors with similar economies. Although most of these states have seen small increases since the Great Recession, the long-term direction is down. (All data are from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and retrieved from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’ FRED database.)

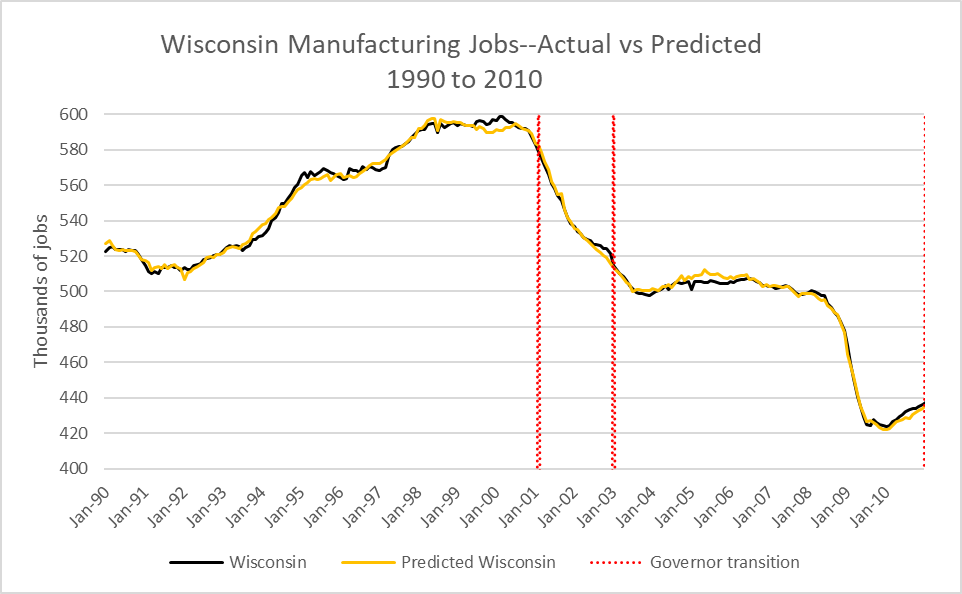

Public policy analysis has been severely limited in its ability to measure the effects of a policy change by the difficulty of determining what would have happened without the change. Just comparing performance in one era with another tells us nothing without finding some way to control for other changes in the external environment. But the fact that Wisconsin is surrounded with states with similar economies offers the opportunity to build a “business as usual” model that can be compared to actual performance.

In a recent column I introduced a model to predict all Wisconsin jobs based on jobs at these six other Midwestern states. The assumption was that these other states’ economies were seeing the same forces as Wisconsin and therefore could be used to predict Wisconsin’s economy.

The comparison proceeded in two steps. The first was to build a business as usual model using the period before the changes under Governor Scott Walker took place and then forecast how jobs should have grown: what it showed was that jobs should have grown by 80,000 more in Wisconsin had the state’s employment numbers continued tracking along with the six other states as it had in decades past.

So what about manufacturing jobs? The next graph shows the years from 1990 (when the data series start) through 2010. As with overall employment, the predicted manufacturing jobs — based on growth seen in six other Midwestern states — track closely the actual manufacturing job growth seen in Wisconsin. This holds true through three recessions and recoveries and a partisan transition from Republican to Democratic governor.

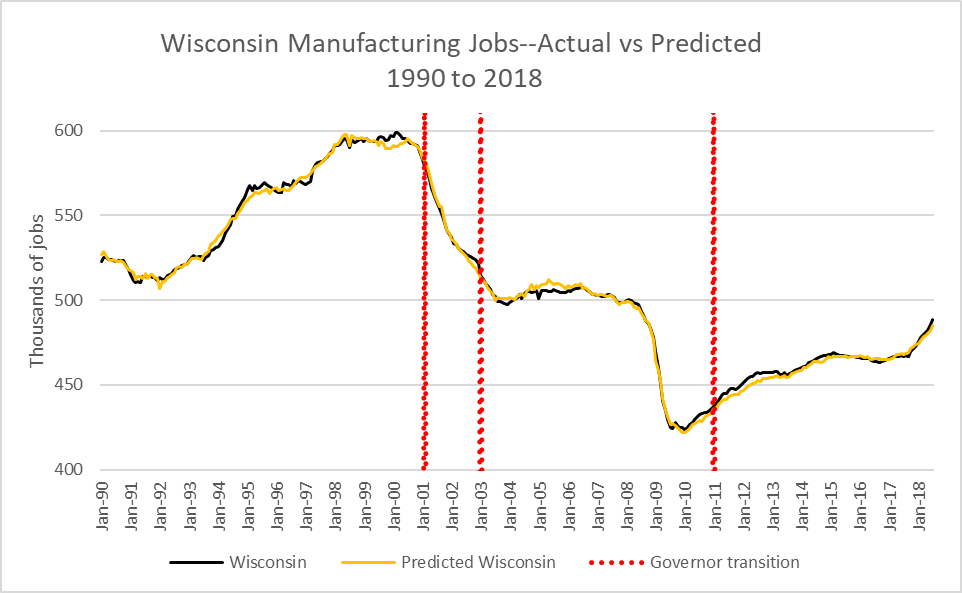

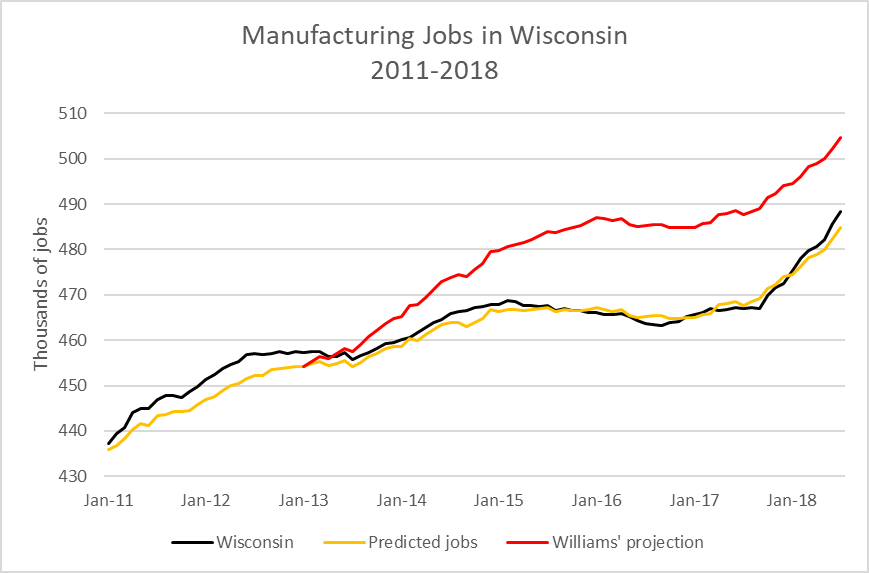

The second step was to apply the model developed in the first step to the period following the change to get an estimate of the number of jobs that could be expected with business as usual. In this case, January 2011, when Walker took office, was the cut point. The part of the graph below starting in January of 2011 shows both the resulting forecast and the actual job numbers, which track very closely. In short, in the case of manufacturing jobs, the state continued to see a performance similar to surrounding states, as it had before Walker took office.

Yet Walker and the Republican-led Legislature had passed the Manufacturing and Agriculture Tax Credit in 2011 as part of the 2011-13 state budget and began to partially phase-in during 2013. The credit took full effect with 2016 tax filings.

If the tax credit increased manufacturing employment in Wisconsin, one would expect that manufacturing jobs would have grown faster than predicted based on historic performance in Wisconsin and surrounding states. Instead, as the above graph shows, the predicted number of manufacturing jobs is all that were created in Wisconsin.

The fact that the introduction of the tax credit did not increase actual manufacturing employment above the business as usual prediction leads to the conclusion that it did not have a significant effect on employment.

A somewhat more sophisticated defense of the tax credit came from Noah Williams of UW-Madison and a Walker supporter. Williams compared manufacturing jobs in Wisconsin border counties to those of their cross-border neighbors. He concluded that, “Applying these border-county estimates to the whole state suggests that since its introduction the (tax credit) accounted for a total gain of over 20,000 manufacturing jobs (a 4.6% increase) and over 42,000 total jobs (a 1.8% increase) in Wisconsin.”

Williams’ analysis ignored the differences between the supposedly matched counties. For example, the Wisconsin counties were substantially less urbanized than their out-of-state neighbors.

The graph below shows in red what the jobs numbers would look like if the projection based on the 1990-2010 period were adjusted upward by 20,000 jobs. Wisconsin should have shown a big gap between predicted and actual manufacturing jobs — which didn’t happen.

The Manufacturing and Agriculture Tax Credit reflects the danger of letting nostalgia for the past drive economic policy, of succumbing to the hope that we can return to when manufacturing drove the Wisconsin economy. While it is important not to write off manufacturing, it is also a mistake to expect a return to the days of well-paid, but low-skilled and highly repetitious mass manufacturing jobs. Those jobs are either being automated away or migrating to nations with much lower labor costs.

In its fixation on manufacturing jobs, Wisconsin runs the danger of neglecting the investments needed to build a new economy. It blocks serious planning for what comes next. Ending the manufacturing tax credit would free up roughly $300 million that could be directed to more productive uses.

Data Wonk

-

Why Absentee Ballot Drop Boxes Are Now Legal

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Error in the last sentence – should be $300 million, not $300,000.

@ajbartelme Thanks… This has been fixed.