Why America’s Roads Are More Dangerous

U.S. and Wisconsin have seen less decline in traffic fatalities than other countries. Why?

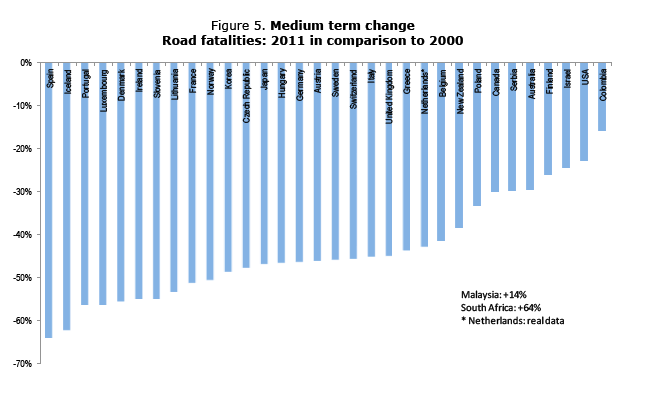

The United States continues to fall farther behind peer nations in reducing traffic fatalities. Image: International Traffic Safety Data and Analysis Group

Vox, the much-anticipated Ezra Klein/Matt Yglesias/Melissa Bell reporting venture, launched recently to wide fanfare, and one of the first articles explained that “traffic deaths are way, way down” in the United States.

It was exciting to see Vox show an interest in street safety, but writer Susannah Locke missed the mark with her take on the issue.

Locke called a decades-long reduction in traffic deaths to 33,561 in 2012 “a major public health victory.” This meant that only 11 of every 100,000 Americans were killed in traffic that year, which, she rightly points out, is a dramatic improvement compared to the 1970s, when the fatality rate was 27 per 100,000 people.

But compared to our international peers, the United States is still doing a poor job of reducing traffic deaths. Rather than hailing the decline in traffic fatalities in America, we should be asking why we continue to fall behind other countries when it comes to keeping people safe on our streets.

What’s shocking is not only that those countries have much lower rates of traffic deaths — it’s that they’ve also reduced those rates at a much more effective clip than the United States. The streets of our peer countries are becoming safer, faster.

In Japan, the traffic death rate fell 47 percent between 2000 and 2011. Sweden’s fell 49 percent, Germany’s 46 percent, and the UK’s 49 percent. In the same time frame, the improvement in America was just 30 percent. Only developing countries like Malaysia, South Africa, and Colombia performed worse in the international review.

Locke does acknowledge that “there are still too many people dying” but seizes on the diverging diamond interchange as an example of an exciting innovation that could further improve traffic safety. Designed to reduce conflicts between drivers, the diverging diamond is at best a Band-aid — it makes driving safer but doesn’t address America’s dangerous dependence on cars. Chuck Marohn of Strong Towns has called the diverging diamond an “apostasy when it comes to pedestrians” and “proof the engineering profession is failing us.”

Todd Litman of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute would refer to the diverging diamond as the “old transportation safety paradigm.” Litman points out in a recent piece on Planetizen that even as deaths per mile driven declined in the last 50 years in the U.S., increases in per capita driving eroded much of the safety benefit. In addition, safety fixes aimed at reducing the risks of driving — like airbags — sometimes have the unintended effect of promoting riskier behavior.

“As a result, measured per capita, traffic accidents continue to be a major problem and the U.S. has the highest crash rate among its peers,” Litman writes. “From this perspective, conventional traffic safety programs have failed and new approaches are needed.”

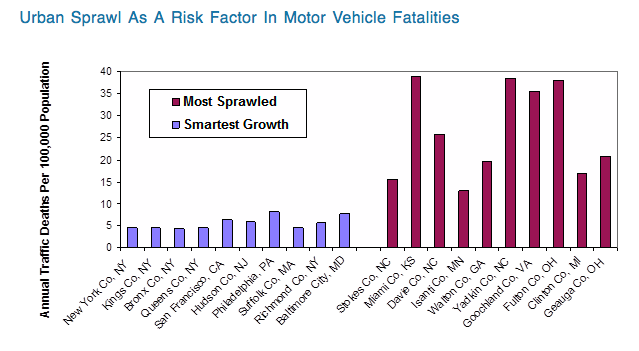

Graphic: Todd Litman/Planetizen

The factors Locke cites to explain America’s declining traffic death rate mostly fall under the rubric of “conventional traffic safety programs” — more seatbelt wearing, better airbags, anti-lock brakes, and less drunk driving. This is where looking abroad really would have helped, because the range of tactics other countries have deployed is much broader.

In the UK, 20 mph zones have been steadily growing since the turn of the century, and automated traffic enforcement is saving lives. The Dutch abandoned a street design philosophy based on “forgiving” errant drivers (which America embraced), shifting to an emphasis on walkable, bikeable streets. Japan has perhaps the world’s best transit networks, making driving less necessary. Germany is a pioneer in traffic-calming street design. Sweden, as the Economist recently reported, cut pedestrian fatalities in half over the last five years with a strategy that included low speed limits in urban areas and building 12,600 safer street crossings.

These solutions are catching on in some U.S. cities. New York is rolling out 20 mph zones in some neighborhoods and has re-engineered wide streets to make biking and walking safer. Chicago and DC have substantial speed camera programs in addition to growing networks of protected bike lanes. What impact are these changes having on traffic fatalities? How many lives could be saved if we scaled up these safety improvements nationwide? What else can we learn from countries that are leading the way in preventing traffic deaths?

Those are Vox stories I’d like to read.

And Here in Wisconsin?

Wisconsin has the most lax drunk driving laws in the country, and doesn’t appear to be moving quickly to stiffen penalties. Bill Lueders reported in January 2013 that Assembly Speaker Robin Vos questioned a new effort to stiffen penalties saying they needed, “to take a closer look at the bill draft and the fiscal estimates to see if spending nearly a half a billion dollars is the best way to prevent people from driving drunk.”

Although the Milwaukee Police Department recognizes that deaths involved with pedestrian automobile collisions are dramatically reduced from 45 percent to 5 percent when the speed of the car is reduced from 30 MPH to 20 MPH, there has been no local effort to reduce speed limits in the city to 20 MPH.

Statewide, we may be moving in the opposite direction. In October 2013, a bill sponsored, by Rep. Paul Tittl, to raise the speed limit on Wisconsin’s freeways to 70 MPH was passed by the Assembly.

And it looks like the diverging diamond is on its way to Wisconsin. In March, Rachelle Baillon, of Fox 6 Now reported that the Wisconsin Department of Transportation is investigating the use of a diverging diamond for the intersection of I-43 and Brown Deer Road.

On the plus side? In 2009 Gov. Jim Doyle signed into law Wisconsin’s complete street legislation. The legislation established rules for where and how bicycle and pedestrian improvements are required to be made during road construction projects. And just recently, Gov. Scott Walker signed into law additional education requirements for drivers students regarding bicycle safety. But Wisconsin and the U.S. have a long way to go before they begin to approach the traffic safety achieved abroad.

Diverging Diamond Visualization

Story by Angie Schmitt with additional contributions from Urban Milwaukee. A version of this story originally ran on Streetsblog. Angie Schmitt is a newspaper reporter-turned planner/advocate who manages the Streetsblog Network from glamorous Cleveland, Ohio. She also writes about urban issues particular to the industrial Midwest at Rustwire.com.

Streetsblog

-

Car Culture Cements Suburban Politics

![Sprawl. Photo by David Shankbone (David Shankbone) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons [ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ASuburbia_by_David_Shankbone.jpg ]](https://urbanmilwaukee.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/1024px-Suburbia_by_David_Shankbone-185x122.jpg) Nov 23rd, 2018 by Angie Schmitt

Nov 23rd, 2018 by Angie Schmitt

-

Most Drivers Don’t Yield to Pedestrians

Mar 22nd, 2018 by Angie Schmitt

Mar 22nd, 2018 by Angie Schmitt

-

Jobs Up Yet Driving Down in Seattle

Feb 22nd, 2018 by Angie Schmitt

Feb 22nd, 2018 by Angie Schmitt

great article…….

But I wonder about 20 mph zones. The default is 25 today in Milwaukee. The data I have seen suggests it is pretty difficult to get killed in car going less than 30 mph.

Thomas: I think the idea is that “traffic” deaths cover those in vehicles, those on bikes and motorcycles as well as pedestrians who are struck by cars. Reducing from 30 may help those outside of vehicles, at the very least reducing their injuries.

The article has an issue with separating the differences in traffic fatalities. Reducing traffic deaths in vehicles is a completely separate issue from reducing pedestrian and cyclist fatalities. Raising highway speed limits to 70mph is not the “opposite direction” of lowering city speed limits because they’re two completely different situations. You don’t lower city speeds for car-to-car incidents as they are already low enough for that. You lower them for pedestrian issues that aren’t a factor in highway situations.

I also don’t necessarily agree with the idea that the best solution for improving safety is getting fewer people to drive. That’s not really a “solution” to a safety problem, that’s simply reducing the number of users. There is a level of danger in all methods of transportation whether it be personal vehicle, bus, train, plane or boat. Want to improve aviation safety? Get fewer people to fly. Improve train safety? Get fewer people to ride trains. It doesn’t really make a very useful argument. It’s probably better to stick to public transit encouragement on the anti-car rhetoric and avoid trying to use a public safety perspective.

I think we should just outlaw the automobile… then we’d have 0 deaths per 100,000 people. Better yet, maybe we can continue to let the price of gas artificially rise to a level of $10/gallon since the high price of gas is a primary contributor to less people driving (and thus less accidents).

The city of Milwaukee sees 3 times the number of homicides then it does traffic fatalities. Besides the fact that the MPD does not enforce speed limits, I think we’d be better served by spending more money on policing and educating the city then we would by spending more on messing with our traffic infrastructure.

Regarding the state as a whole… if almost half of all traffic fatalities were because the occupant was not wearing a seatbelt, if we were able to increase seatbelt use we could close the gap with our so-called peer countries. Currently the US seatbelt use hovers in the low to mid 80% range… compared to European countries that are in the upper 90% range.

Regardless, we need to compare apples to apples… comparing deaths per x population is pointless. We need to look at deaths per x miles/km driven… In this respect, we are on par or better than most of the countries cited. In the case of Japan, not only are their vehicle deaths per km/traveled much higher, their pedestrian deaths are ridiculously high. Is this who we would like to emulate? Or maybe we’d rather be like the French, who despite having seatbelt use rates near 100%, have a fatality per km/driven rate almost a fifth higher than the US.

This is more cherry picking of data to further the fight against the use of the automobile and I can hardly think of it being more blatant.

Andy, comparing automobile deaths per million population is NOT “pointless”.

Vehicular death rates are not a measure of drivers’ skills but a measure of how our country is laid out, and the US is laid out in a way that kills more people (per million) than in many other countries. The fact that this design requires more vehicle miles for daily living is not some neutral factor, but a major cause of those deaths.

Instead of vehicular deaths, consider lung cancer deaths. If more people took up smoking and an increase in lung cancer rates (per million) followed, I would argue this is a bad thing, but I think you would claim it wasn’t really a problem–since it was just caused by having more smokers (just as you shrug off higher vehicular death rates as just an effect of high VMT rates).

Hi Tom,

I’ll grant you that the statistic for fatalities per population is not completely pointless, it is only pointless when you are writing an article about making roads safer. Of course I agree with you that we can eliminate vehicle deaths if we reduce the number of people driving cars… just like we can reduce the number of bike deaths by stopping people from riding their bikes (poor Netherlands, 22% of their deaths involve bikers!) and pedestrian deaths by keeping people off sidewalks and locked in their homes. Do those sound ridiculous to you? Because that is how the argument about reducing vehicle use for the sake of saving lives sounds to me. Our opinions on that subject may differ, but if we are comparing countries in terms of how much they improve automobile safety then the only logical comparison is deaths per mile driven.

I’ll take a line right out of the report that Ms. Schmitt is working from: “Fatalities per billion vehicle–kilometres… …is the most objective indicator to describe risk on the road network.”