How The Sewerage District Came of Age

The Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District has been a national leader since its formation. Part 1 of a three-part series.

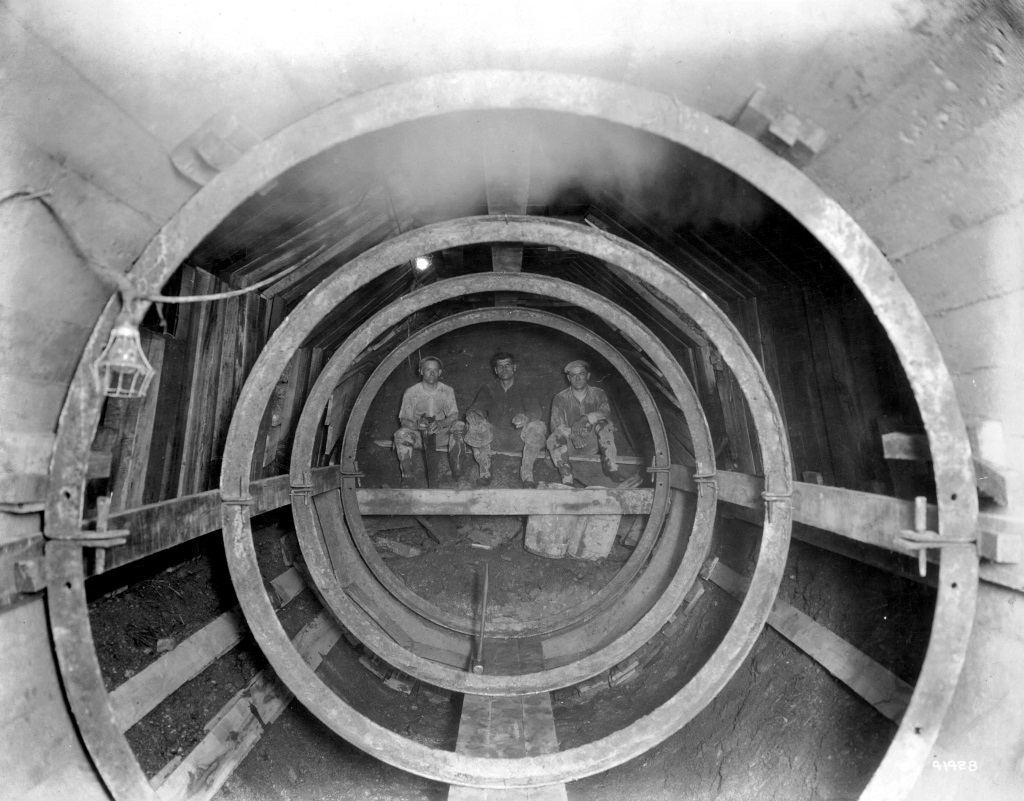

Lunch break for workers building metropolitan interceptor sewers (Brady St.), 1924. Photo courtesy of MMSD.

Milwaukee has been a leader in wastewater management since the late 19th century. The city was one of the first to build combined sewers, to install a treatment plant and to use biological processes to treat waste. Already ahead of many of its peers, in the post-World War II period, the city recognized the need to create a second treatment plant in what was then a distant suburb. When the Clean Water Act of 1972 dictated higher standards for clean water, the city capitalized on what might have been the last opportunity to use federal grant money—as opposed to loans—to prevent sewage overflows by building the Deep Tunnel. With its engineering know-how, the city has always shown the rest of the country how to manage storm water and sewage. Today Milwaukee is once again in the lead nationally in making the transition from the traditional “gray infrastructure” water management practices to the forward-looking methods of “green infrastructure” as it takes on the challenges of growth, aging infrastructure and climate change.

The awards that the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD) and its Executive Director, Kevin Shafer have won for this work include the U.S. Water Prize from the U.S. Water Alliance and the National Association of Clean Water Agencies public service award. Shafer has also been given the Lloyd D. Gladfelter Award for Government Innovation from UW-Madison’s Robert M. LaFollette School of Public Affairs and the Public Policy Forum’s Norman H. Gill Award. In 2007, MMSD won the Kodak American Greenways Award for the District’s Greenseams Program, and in April of this year, Shafer was given the Edward J. Cleary Award from the American Academy of Environmental Engineers and Scientists.

Shafer and the MMSD have won these awards for a range of successes: reducing combined sewage overflows from over 50 a year to under three, using the Greenseams program to acquire 3,000 acres of open land, creating public-private endeavors that expand the use of green infrastructure and bringing nature back into the city by helping convert industrial wastelands like the Menomonee Valley and the 30th Street Corridor into greenways and bike trails. The MMSD’s plans for the future, articulated in its Vision 2035, include zero overflows and 100 percent renewable energy usage.

Yet Milwaukee just can’t bring itself to love its sewage district as much as the rest of the country does. Talk radio in particularly has slammed the MMSD with misleading claims.“The community doesn’t recognize how good that organization is,” says Pat Marchese, who served as MMSD’s Executive Director from 1984-1988. “They don’t understand how creative and progressive Kevin has been.” And that’s okay with Shafer. “Criticism,” he says, “helps us do our job better.”

MMSD and Shafer’s success is possible, in large part, because it’s been built on the past success of the city, which has always been ahead of its peers in how it manages its sewage and storm water. Marchese describes that history as having four phases, the first starting in the late 19th century that he calls, “Oh my God! What are we going to do with this human waste?”

The birth of that system appears in an 1889 report entitled, “Report of the Commission of Engineers on the Collection and Final Disposal of the Sewage and on the Water Supply of the City of Milwaukee.” At that time, the city of 210,000 was dumping its waste into the city’s rivers, which were then carrying it, untreated, into Lake Michigan. The Milwaukee River, in particular, was a putrid mass of waste that the city had attempted and failed to fix by installing a tunnel that flushed Lake Michigan water upstream to dilute the concentration of waste in the river. After touring cities in North America and Europe, the engineers who authored the report offered possible solutions like the cesspools they’d seen in Paris, portable receptacles collected weekly by city workers, spreading waste over open fields outside the city, and, finally, what they called a “water carriage” system used in both England and Germany in which water was carried to a central location for treatment. Two different kind of water carriage systems were used, the report explained. “One called the ‘combined’ and the other the ‘separate’ system.”

The city dallied, ended up with a second flushing tunnel on the South Side and then face a typhoid outbreak in 1907. State legislation entitled, “An Act Related to Sewage Disposal Works in Cities of the First Class,” prompted the city to appoint a five-person sewerage commission whose first order of business was to hire the District’s first Chief Engineer, T. Chalkley Hatton, who was appointed on January 6, 1914, at an annual salary of $10,000 The District’s first chemist, William M. Copeland, was hired away from New York City’s sewerage district at the same time.

The Sewerage Commission divided the city into districts based on the population it projected for 1950. They mapped out locations for interceptor tunnels and then agreed they needed to test different methods of sewage treatment before settling on the one they would use. “In fact,” says the “First Annual Report of the Sewerage District of the City of Milwaukee,” “no large treatment plant in this country or abroad, capable of treating fifty million gallons or more of sewage per day has been designed without (conducting) a series of experiments… in the treating of the actual sewage.”

Having thus agreed on a plan, the commission’s next order of business was to fight with the city about paying for it. A series of letters fired back and forth between the commission and the City Attorney’s office show that the newly appointed commissioners resisted the city’s demand that they submit a budget for the following year. As George P. Miller, the sewerage commission’s Vice-Chair astutely pointed out: “The adoption of the budget acts as an appropriation bill.” Once that budget was submitted and approved, by law, the Common Council had to raise the money for it through taxation. But George H. Benzenber, commission chairman, explained to the city’s Board of Estimate that they could only submit an accurate budget once the work of the sewerage commission “assumed a fixed character.” In its first year, the sewerage district’s appropriation was $100,000, of which the commissioners spent a little over $71,000. By 1917, the total income reported by the Sewerage District, which included a mill tax, a bond issue, and credits from the sewer department and Ford Motor Company, totaled $2.3 million. With the money, the District had to figure out how to connect the drains so the waste ended up at the new treatment plant at Jones Island, and they also had to figure out what to do with it when it arrived.

As early as 1914, the engineers and sewage commissioners were interested in the “activated sludge process” designed by Dr. Gilbert Fowler in Manchester, England. Activated sludge used biological organisms that ate the waste, converting it to nitrogen rich fertilizer. The city contracted Fowler to develop that process in Milwaukee, but by 1925, it was still not installed, much to the frustration of Hatton, who told the Lake Michigan Sanitation Congress that year: “For over forty years the city of Milwaukee has studied ways and means for disposing of its sewage other than by dumping it untreated into Lake Michigan, from whence it obtains its water supply…” But all those studies and the reports of the past four decades had been “in vain because the people refuse to appropriate any funds for the work recommended (since) they were not sufficiently impressed with its importance.”

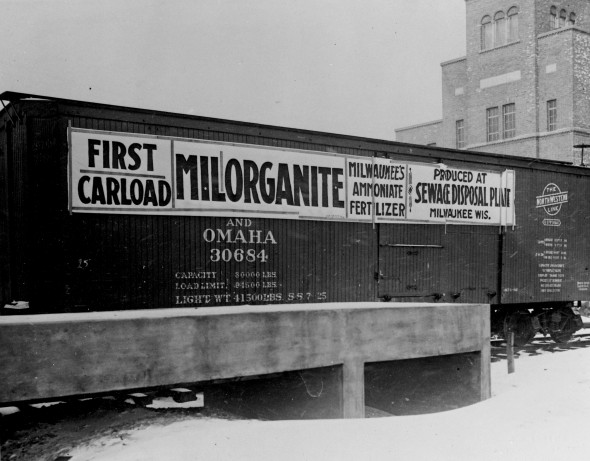

Not only was the work not sufficiently impressive, Hatton continued, but: “Nearly everyone interested in the development of the Activated Sludge process was doubtful of the ability to find a suitable market for the sludge when reduced to a fertilizer base.” Hatton and the sewage commission, though, were confident. Milwaukee’s biggest challenge — dealing with the high volume of waste from the city’s breweries — was also its advantage in that the brewery waste produced fertilizer was especially high (7 percent) in nitrogen content. Even though no sludge had yet been produced, Hatton reported, they already had as many contracts as they could manage from fertilizer manufacturers eager to snatch up waste.

By 1925, that process was brought in-house and the Sewerage Commission started marketing Milorganite, which quickly became a huge success. Even today, it continues to be not only a top selling fertilizer, but also, according to Milorganite’s website, “one of the world’s largest recycling efforts.”

By this time the city and county had each combined their separate sewerage commissions, recognizing that the population growth outside the city was expanding the problem to be solved. In 1921 the the Metropolitan Sewerage District of the County of Milwaukee was created.

The next phase on Marchese’s timeline is Post WWII growth. Jones Island was expanded in 1934 and again in 1952 and the District built a second treatment plant in 1968 at what was then the distant suburb of Oak Creek. While this expansion was going on, a new environmental movement was taking shape, spurred on by a series of articles by Rachel Carson that were first published in The New Yorker, and later collected into her book, Silent Spring. She warned readers about the threat of pesticides and advocated for controls on pollution. Although the Federal Water Pollution Act had been passed in 1948, the environmental movement led to its 1972 revision into a law now known as the Clean Water Act.

At the time it was passed, Milwaukee’s sewers were overflowing and dumping untreated sewage into Lake Michigan over fifty times per year. Under the Act’s provision, the State of Illinois and Wisconsin’s Department of Natural Resources sued Milwaukee’s Sewerage District in 1977 and 1978, prompting the creation of the Water Pollution Abatement Program. Disputes over how to finance the program led the state legislature to create the MMSD, an expanded district which encompassed not just the city and 17 suburbs in Milwaukee County, but an additional 10 suburbs in parts of Ozaukee, Waukesha and Washington counties and a portion of Caledonia in Racine County. The expansion recognized that sewage and pollution flowing into rivers like the Milwaukee, Menomonee and Kinnickinnic did not recognize geographic boundaries, and that no plan could succeed that that did not include all contributors to the problem.

The proposed solution to the suit — the building of Milwaukee’s Deep Tunnel — set off a period that Milwaukee residents might remember as the “sewer wars.”

One proposed solution was to separate the sewer and storm water tunnels to insure that the only water that got treated was actual sewage. Then the volumes of storm water that were causing the overflows wouldn’t even go into the treatment system. This kind of separation had been done in newer municipalities, but not in Milwaukee and Shorewood. In a 1979 report the District’s engineering consultant, CH2M Hill, concluded that separate sewers would be more cost effective over the long run because that was the only way to guarantee that only waste, and not clear water, was being treated. But the cost to replace the combined system with the separate system would be unfeasible for residents in Milwaukee and Shorewood. Because the pipes that connected their homes and businesses to the District’s system were on private property, the cost of disconnecting them, creating a separate line and reconnecting both to a new District system, would be borne by private residents. That cost, the consultants estimated, would be about $4,000. They pointed out that 19 percent of all households in Milwaukee at that time had an annual income under $5,000 and another 23 percent had incomes of $5,000 to $10,000. Rather than pay, the report warned, “landlords may be induced to abandon their structures or accelerate deterioration by withholding needed maintenance.” Loans might also prove elusive, which would put the city in the position of having to sponsor a loan program for homeowners who could not get one through traditional means. For middle-income families, the situation wasn’t much better. Replacing sewer lines could be as high as 40 percent of total housing costs for families who would not have access to tax-relief programs that were available to low-income families.

The other solution was to build another tunnel under the existing system into which overflow could be dumped when backups threatened. The proposed Deep Tunnel would provide an additional 581 million gallons of storage capacity until the Jones Island and South Shore Treatment plants—each could process about 300 million gallons a day—could handle the overflow. Since the entire district, not just those living in the combined sewer area, would benefit from the tunnel, CH2M Hill’s report concluded that the costs could be shared.

Not everyone agreed. Suburbanites and city dwellers lined up on opposite side of the issue. Most vocally represented by a group called FLOW (Fair Liquidation of Waste), which represented residents from Butler, Menomonee Falls, Mequon, New Berlin, Elm Grove, Germantown and Thiensville, opponents of the Deep Tunnel argued that its cost unfairly impacted them, by allocating costs based on property value rather than per the amount of water used. They accused the city of trying to undermine suburban growth. An April 4, 1980 article in the Milwaukee Journal quotes protest signs at a Nicolet High School public meeting: “Must We Do Together What Milwaukee and Shorewood Goofed?” But Mequon city administrator Donald Roensch concurred with MMSD’s decision to share costs, saying that the were, “too much for one community to bear.”

Franklin’s colorful mayor, Theodore Fadrow, perhaps the most histrionic of the protesting city officials, claimed that the $1.65 billion estimate of the cost sharing plan was a “rape of the people.” “You’re going to have a revolution on your hands,” he threatened the District’s commissioners.

The Deep Tunnel went online in 1993. By the time it was finally done, the total cost of the Water Pollution Abatement program was $2.3 billion. But 55 percent of that was funded by the federal government. Those kind of granting opportunities, says Marchese, later disappeared during the Reagan era as Congress shifted such funding to loan programs. In short, Milwaukee’s timely decision-making process helped this metro area save more than a billion dollars, money that other cities would have to spend as these grants ended. As for the idea of separating storm and sewer tunnels, over time Milwaukee and other cities would learn that all tunnels end up leaking and that separation doesn’t insure that only waste water was treated, as CH2M Hill had once concluded.

But the furor over the Deep Tunnel had an impact that can still be felt today, and helps explain the vitriolic comments of talk radio hosts like Mark Belling toward the MMSD. When Shafer first joined the organization as Head of Engineering in October of 1998, there was still deep mistrust and animosity toward the utility that was on the cusp of entering the fourth age of Marchese’s timeline. “I never know what to call this phase,” he says. But it began with a recognition by Shafer that building tunnels wasn’t going to be enough. The world was changing, and the MMSD would have to change with it.

Combined Sewer Outlets, 1931

Deep Tunnel Construction

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

The MMSD Story

-

Every Drop Counts

May 28th, 2015 by Susan Nusser

May 28th, 2015 by Susan Nusser

-

From Gray to Green

May 21st, 2015 by Susan Nusser

May 21st, 2015 by Susan Nusser

Some great coverage on an under appreciated (yet all too critical) sector of public works. Plenty of information that ought to clear up misconceptions – especially on the divide Deep Tunnel!

This will do nothing to shut up the blathering fools but I look forward to the rest of this series. To say our sewer system is underappreciated and misunderstood is an understatement.

Time to rethink sewage sludge, biosolids and reclaimed wastewater. http://alzheimerdisease.tv/alzheimers-disease-spreading-faster-via-biosolids-reclaimed-water/

Kevin was/is the first Exec. Director with a brain and human qualities

Another great story by Urban MKE. MMSD is a hidden gem of local government in MKE – unappreciated and unloved but doing good work by taxpayer, our rivers, and Lake Michigan. Keep innovating!!!