Wisconsin Scientists Are Leaders in Testing Psilocybin Treatments

Clinical trials show psychedelic drugs can be effective in mental health treatment.

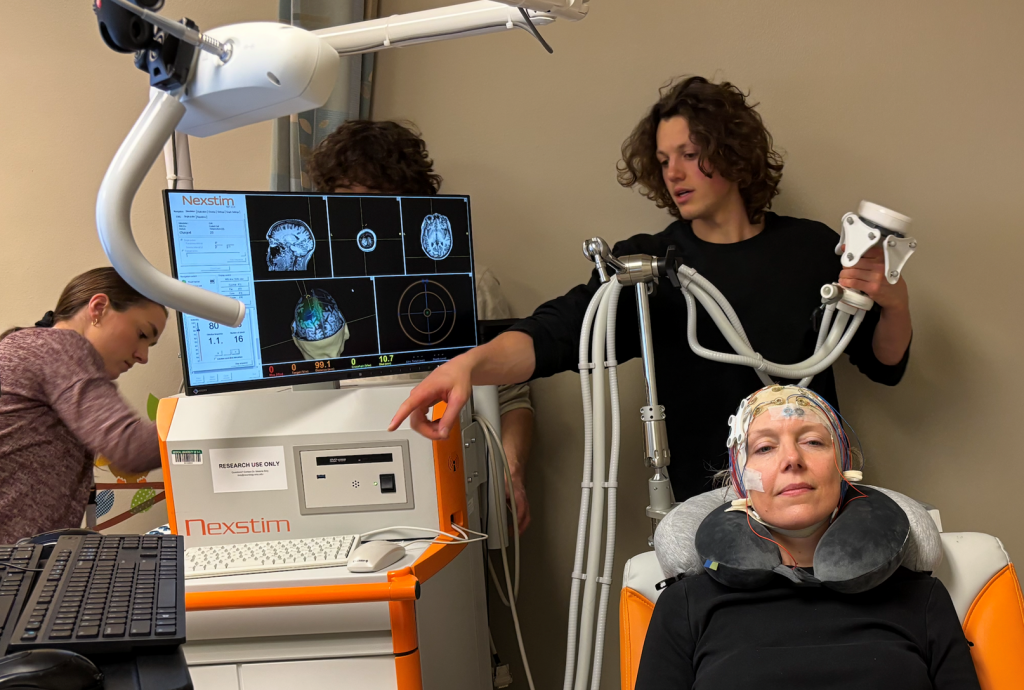

UW-Madison researchers in professor Charles Raison’s lab study how psilocybin works in the brain. Here, study team members Emma Bublitz (left), James Barlow (behind screen), Michael Sutherland (center right), and Laura McCormick (in chair) set up an electroencephalogram to measure her brain’s electrical activity. Photo courtesy of the Raison Lab

For years, Becca Kacanda was haunted by trauma that led to post-traumatic stress disorder. She tried different types of talk therapy and even a technique known as eye movement desensitization and reprocessing.

Nothing stuck.

Then in 2020, she found a clinical trial at the University of Wisconsin-Madison testing the psychedelic drug MDMA, paired with therapy, to treat PTSD. Scientists were testing a new use for the drug, which is commonly known as ecstasy or molly and associated with dance clubs and raves.

The trial was one of many probing whether mind-altering psychedelics could help people who haven’t had success with available mental health treatments. Some researchers hope these federally illegal drugs, historically used recreationally and without regulation, might hold clinical promise in the treatment of conditions such as depression, addiction and PTSD.

And for Kacanda, it worked.

“I felt like I was like a volcano ready to explode at any time before, because there was so much under the surface with that trauma,” Kacanda said. “It’s not even part of my reality at all anymore.”

Now, the Milwaukee mosaic artist said, thoughts that used to preoccupy her mind barely stick around. She’s training to be an art therapist. And though the treatment five years ago didn’t magically free her life of struggle, it made a lasting impact on her PTSD symptoms.

“I feel like there’s a permanent change with it. I don’t feel like I have any risk in slipping back into it,” Kacanda said.

Last year, federal regulators rejected MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD. Despite Kacanda’s experience, a Food and Drug Administration advisory committee concluded more work was needed to document unwanted side effects and “blind” participants who are receiving a mind-altering psychedelic drug, versus a placebo.

Regulators sent the treatment back to the lab for more testing. In the meantime, work continues on clinical applications for other illegal drugs. In Wisconsin, scientists are testing whether psilocybin, the psychoactive ingredient in magic mushrooms, could help patients with conditions like depression. And they think psilocybin could be next up for federal approval.

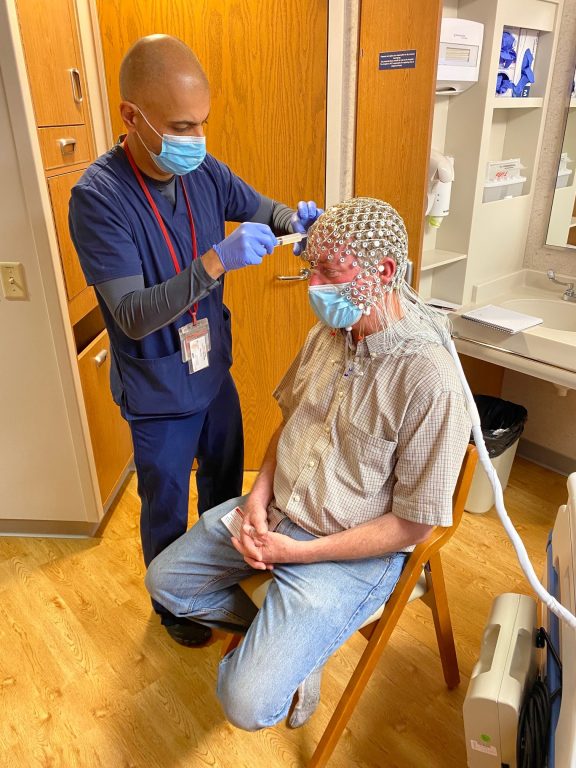

UW-Madison professor Charles Raison (wearing an electroencephalogram cap) conducts studies on consciousness and psychedelics. Photo courtesy of the Raison lab

A lab that looks like a living room

Clinical psychologist and neuroscientist Christopher Nicholas helped run the trial Kacanda took part in. He continues to test psychedelics for conditions like opioid use disorder at UW-Madison. Nicholas often guides participants through their psychedelic experience as a facilitator.

He said Kacanda’s experience is not uncommon.

“A lot of the participants in our trials have tried one or more different types of either behavioral treatments or pharmacological treatments,” Nicholas said. “They’re looking for another option.”

He’s optimistic psychedelics paired with therapy will give patients a new tool. He worked on a 2023 study that found participants’ depression scores improved about six weeks after a single dose of psilocybin.

UW-Madison professors Charles Raison and Christopher Nicholas run clinical trials probing the therapeutic potential of psychedelics and study how the drugs work in the brain. They’re pictured on July 28, 2025, in the room they host trial participants. Anna Marie Yanny/WPR

Scientists don’t give psychedelic drugs to everyone. For example, people with psychotic disorders or high blood pressure aren’t eligible for trials for fear of exacerbating these conditions. Like other participants, Kacanda underwent medical screening and preparatory therapy before trial facilitators gave her a psychedelic pill on her “dosing day.”

The room where the sessions take place is warm with nature art on the walls and bowls of snacks next to a couch and two armchairs.

“Participants often are very surprised that they’re enrolling in a research study,” Nicholas said. “They come into this room and they’re like, ‘Wow, this feels great. This is a really nice environment.’”

Here, facilitators like Nicholas guide participants through hours-long hallucinations and sometimes intense “trips.”

“They often wear headphones, listen to instrumental music, and we really encourage them to just be within their experience, to focus on what comes up personally for them,” Nicholas said.

The room where UW-Madison researchers help guide clinical trial participants through psychedelic treatments. Pictured July 28, 2025. Anna Marie Yanny/WPR

Afterward, the participants have follow-up therapy sessions to process their experience.

“I don’t really think (MDMA-assisted therapy) compares to any other form of therapy to be honest,” Kacanda said. “And I say that as someone who’s going through school to be a therapist.”

Many scientists who worked on the trials were optimistic about the findings, so it was a disappointment to some when FDA regulators sent them back to the drawing board on MDMA-assisted therapy.

“We’re still learning about what the FDA is going to require for approval,” Nicholas said. “And I think the FDA is learning as well.”

Some call for decriminalization of the drugs in Wisconsin

On the local level, cities like Detroit, Michigan and Oakland, California have already decriminalized psychedelics — and some are calling on Wisconsin cities to follow suit.

Eric Medina, organizer for Decriminalize Nature Madison, hopes people will have access to psychedelics before federal regulators decide to approve or reject them. His organization is hoping the Madison City Council will approve a resolution that makes psychedelics the lowest enforcement priority for local police.

Medina said he got into this work because he saw his friends and family benefit from psychedelics.

“The biggest risk that they posed to my friends and family was that they might go to jail for them,” he said.

Research shows psychedelics come with risks for some users. A 2022 study surveying people who used them recreationally found 13 percent reported a negative outcome, including substance misuse and suicidal ideation.

Psychiatrist Charles Raison wears an EEG cap while testing procedures with nurses at the UW-Madison Clinical Research Unit. His lab studies how consciousness plays a role in the therapeutic promise of psychedelics. Photo courtesy of the Raison Lab

Wisconsin institute makes psilocybin used in national research

While scientists said the FDA’s decision to reject MDMA-assisted therapy dampened the hype around psychedelic therapies, they’re still studying new treatments to help patients like Kacanda.

Wisconsin researchers wonder whether psilocybin treatment could be the first federally approved therapy of its kind.

Psychiatrist Charles Raison is a UW-Madison professor and the director of clinical and translational research at the nearby Usona Institute. Usona is a nonprofit medical research organization that makes the psilocybin pills and protocols used in research trials across the country. The institute is also one of few places worldwide to get FDA “breakthrough therapy” status for its research into psilocybin treatment for depression, to expedite the treatment’s review.

Raison said in his decades as a psychiatrist, he’s seen many mental health treatments go through “hype cycles.” And psychedelics have been the most intense.

“They went from being these stigmatized agents, almost overnight to (people thinking they’re) going to be this miracle cure for every mental disorder,” Raison said. “And of course, that’s not true.”

But the treatments still hold great potential and shouldn’t be cast aside, Raison said. If approved, his research shows they could help millions.

“They’re going to help some people a lot. They’re not going to help some people at all. Some people, they’ll help a little bit,” Raison said.

Usona is leading a clinical trial testing the safety and efficacy of psilocybin to help treat major depressive disorder. They’re enrolling about 240 people across the country. If the results impress federal regulators, their approval could allow Wisconsinites to get the treatment someday.

“We’re working very collaboratively with the FDA,” said Tura Patterson, Usona’s senior director of strategic partnerships. “We’re doing everything possible to move the process forward as efficiently as possible, recognizing the unmet medical need.”

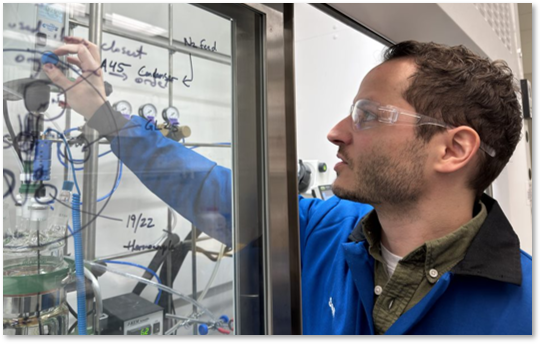

Process Development Research Scientist Sam Williamson at the Usona Institute chemistry lab in Fitchburg, WI. Photo courtesy of Usona Institute

And new federal leadership may work in their favor. Usona’s former chief medical officer Mike Davis was recently appointed as the FDA’s deputy director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. And U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. recently signaled federal support for psychedelic therapies, even making the claim on June 24 that they could be implemented within a year.

But ultimately, Patterson said, “the data needs to stand on its own.”

“There may be a favorable attitude, but I think it is still going to come down to what the FDA requires for any new drug approval,” she said.

Should it be approved, Usona leaders are confident their institute in Wisconsin can be an educational leader for clinicians and health care leaders preparing to provide such treatments.

“I think actually Wisconsin will be at the forefront upon approval,” Patterson said. “There’ll be a number of organizations and individuals that are prepared.”

Wisconsin scientists are leaders in testing psilocybin treatments for mental health was originally published by Wisconsin Public Radio.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.