Why I Love “Degas to Picasso”

On my fifth visit to the Milwaukee Art Museum show I’m still discovering more.

Edgar Degas (1834–1917), Self-Portrait in a Top Hat, ca. 1865. Charcoal on paper, 14 × 9 7/8 inches (35.5 × 25 cm).

The security guard nods in familiar recognition as I walk into the “Degas to Picasso” show at the Milwaukee Art Museum. This is my fifth visit. Even after the fourth viewing, I found myself still thinking about the work on display, which drew me back here yet again.

The doors open and a windswept little Fragonard drawing in the corner is the show’s true start. It is the smoke before the flame and it seems to be conjured out of air, as lines quiver with energy, washes fade and evaporate. This drawing connects the Italian past (Tintoretto and Titian) to this show and to France.

On the next wall, the David, a little gem of a charcoal drawing, is positioned on the wall so that one must bow to be at eye level with it, the cloaked figure peering up as we gaze down. Such a thin small piece of paper. (I was struck by the thought that all of the work in this show unframed — minus the few paintings — would be a stack of paper no thicker than a phonebook). Jacques-Louis David, who painted huge patriotic anthems of France, drew this tiny work while exiled in Brussels after the fall of Napoleon. He drew it from his imagination when he was in his 70s. The old man looks youthful, much more alive than the young woman he is holding. Is this an idealized self portrait? I’m struck at how the marks of the background seem to cover an inner glow. The piece is not perfectly flush on the wall, an edge hangs off of an almost imperceptible bend in the wall and a thin vertical crack from floor to ceiling has formed, very symbolic indeed of this period in French history.

On the adjoining wall is the beautiful line work of David’s teacher, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, but the two Millets await my gaze and I hurry through the galleries to see them. Jean-François Millet is yet another of the mostly French artists in the show, and these two small drawings were done in charcoal on brown paper, both heightened with white. I see a peasant and a seascape. The paper pulp is rough and feels almost like coarse fabric, like the kind the peasant is wearing. The variety of line which indicates grass, trees, animals and worn pattern shows Millet at his finest. No wonder Van Gogh was a huge admirer. Bring reading glasses for this one: look at the woman’s face, it is so subtle, like a Vermeer, there are no lines, light happens with a few marks and dashes — the nose is implied. I can see Millet out in the field, leaning against a tree, creating this spiritual homage to the everyday. Next to it the seascape with figures in action links us back to Fragonard’s sense of movement and freedom. How is Millet able to draw water like that? It feels wet and in motion, the wave hitting the rock splashes, but in reality it is the brown of the paper that is creating the splash. The ragged edge of the adjoining rocks which is created by the charcoal’s darkness completes this alchemy.

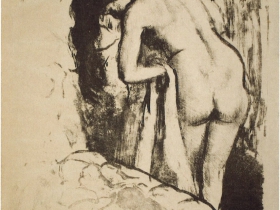

Turn 180 degrees and in the next room are the “Impressionists”, which starts with an early Monet drawing next to a drawing from his mentor, the man that encouraged him to work outside, Eugène Boudin. Intriguing, but I am most drawn to the Degas self portrait that he did in his early 30’s. It is done in charcoal and it appears that he lightly erased the face, which makes it seem veiled and psychologically more real and intense. The top hat seems to be in motion, the byproduct of lines that have searched for an edge. On the opposite wall are two horse drawings (seldom has a horse’s ass been so lovingly and sparsely drawn, I can imagine Degas’ delight in seeing all of the chiaroscuro possibilities at the polo field.)

I then wade through the Degas bathers to the corner of a gallery with two different states of one print by Camille Pissarro. I’m intrigued by the veiled trees and the landscape behind and between them: the focus of the edges changes the way the elements read in space and the different printing states alter the mood and intensity of each piece. From three feet away I’m looking through and into another world and from a few steps closer I relish seeing the technique of a master artist. The marks both depict trees, houses and land while simultaneously being themselves, marks on paper; it’s alive and it’s fresh like the land being depicted. The space reminds me of a Bonnard, where distant houses suddenly jump to the surface because of the intentionally rough roof edge. In the next room is a Bonnard, a little pencil and watercolor of his lifelong model and partner Marta. I turn and see next to it a small pastel by Edouard Vuillard, dark and sparse but glowing.

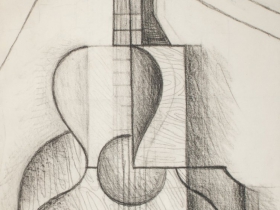

A group of Cezanne drawings and watercolors is on an adjoining wall. The first drawing is a tiny, energized study of bathers. I loved being in this drawing’s energy and thinking of Cezanne holding a small sketchbook more than 100 years ago. I move to the large watercolor of trees. There are ghost pencil marks evident like construction beams, faint in the distance and one can see the building of Modern Art, of cubism. These marks are beautiful and create an otherworldly space that Picasso and Braque recognized and built on, as shown by the selection of works in the following galleries.

My last stop is in the Picasso room which spans his 70-year career and gives us a mini-retrospective of his works on paper. I keep going back to the abstract gouache called “The Musicians” or “The White Coffee Table”. Picasso is playing with our sense of perception of reality. It looks like a pure abstract painting but there is one shape that casts a shadow. Everything else is flat, but Picasso puts in this one illusion of reality. The colors are that of Necco wafers and the work’s sense of play and experimentation is tangible.

As I exit the museum, I’m surprised yet again that a show with mostly small pieces could be so monumentally powerful and am moved by the energized intimacy of the work, which already beckons me to return.

Degas to Picasso Gallery

Todd Mrozinski is a Milwaukee artist whose next exhibition is at the Thelma Sadoff Center for the Arts in Fond du Lac in April.

Art

-

Winning Artists Works on Display

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

-

5 Huge Rainbow Arcs Coming To Downtown

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

-

Exhibit Tells Story of Vietnam War Resistors in the Military

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

Review

-

Ouzo Café Is Classic Greek Fare

May 23rd, 2024 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

May 23rd, 2024 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

-

‘The Treasurer’ a Darkly Funny Family Play

Apr 29th, 2024 by Dominique Paul Noth

Apr 29th, 2024 by Dominique Paul Noth

-

Anmol Is All About the Spices

Apr 28th, 2024 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

Apr 28th, 2024 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

beautifully written Todd…though I can’t imagine anyone but art historians taking the time to read it…you should start and art magazine, something like the former Art Muscle which is now online in the UWMilwaukee archies.

I am printing your article out so that I may have it with me when have my second visit of this show!