Broadway, the Street of Tragedies

Three of the most tragic incidents in city history happened on Broadway.

Milwaukee’s Broadway, like the famous avenue in New York, is wider than the average street. Originally called Main Street, the Common Council renamed it Broadway in 1870. There was criticism that the change was made only in hopes of increasing the value of properties along the street. Broadway is one of only a few streets in the city, like Back Bay and Tory Hill, that have no suffix, such as street, avenue or lane.

Three major tragedies took place on N. Broadway. One was caused by an arsonist, one by ferocious winds, and the other by an anarchist’s bomb.

It was nearly 4 a.m. on a cold morning on January 10, 1883. The night watchman, Bill McKenzie, was on his rounds of the six-floor Newhall House hotel on the northwest corner of Broadway and Michigan Street. While on the sixth floor he noticed smoke coming from the elevator shaft. Rather than awakening the slumbering guests and hotel employees, he got into the elevator and descended. There had been other fires at the hotel in recent years. The hotel proprietor, John Antisdel, told the hotel staff that in the event of another fire, they should not alarm their guests. Instead they should find the source of the fire and try to extinguish it.

There were fire escapes on the Broadway and Michigan Street sides of the hotel, but there was no signage inside the building indicating where the doors to them were. There was no fire escape on the west side of the building where most of the hotel staff lived on the upper floors. With the hallways outside their rooms filled with smoke and fire, a dozen employees jumped to their deaths in the alley below. Others jumped, or tried to jump, into an early form of a safety net, a canvas held by firemen, but no one survived the leap.

Everyone on the second floor escaped but the survival rate dropped with each ascending floor, with only four people on the sixth floor escaping the inferno. In less than half an hour, seventy-two of the 177 people who were in the building were dead or dying. The charred remains of 47 bodies were taken from the burnt rubble over the next 10 days. Nearly half of the victims were Irish, mostly young women who worked at the hotel. The authorities determined the fire was started intentionally, but the arsonist was never found.

The nation was horrified at such a loss. The most fatalities in a hotel fire in the United States up to that time had been 11 people, as far as I have been able to determine. Hotel clerks in New York and Chicago complained that no registering guests wanted to be lodged above the third floor of their hotels.

The tragedy motivated cities across the country to make their downtown buildings safer. Telegraph wires were buried under streets, and ordinances requiring more fire escapes on buildings were enacted. The number of watchmen per hotel was increased. In the following years, these and other changes were credited with saving an untold number of lives. The Newhall House fire held the dubious record for hotel fire fatalities until 1946, when 119 people died in a hotel fire in Atlanta, Georgia.

On October 28, 1892, 50-mile per hour winds spread a fire that started in a building on N. Water Street south of Detroit Street (now E. Paul Avenue). The winds, shifting from west to north and back again, carried the fire to the east, destroying everything in its path to Lake Michigan. The shifting winds also blew the fire southward and nearly every building on Broadway from St. Paul Avenue south to Erie Street was leveled, including the fire station.

The conflagration displaced 350 families, most of them Irish. Many did not rebuild and the make-up of the Third Ward changed. Warehouses and industrial buildings replaced many of the destroyed homes, more Italians moved in and, among other changes, Commission Row was developed.

On November 24, 1917, a suspicious package was found near a Third Ward church where an Italian anarchist preached. The janitor of the church took the parcel to the central police station on the northeast corner of Broadway and Oneida (now E. Wells) Street.

While one of the detectives inspected the package it exploded, killing him, six other detectives, two policemen and a civilian. The bomb maker was never found. The device was apparently meant for the preacher who was at the center of a dispute between rival Italian anarchist groups.

The bombing was the largest loss of police officers’ lives in one incident in the country’s history until September 11, 2001, when 72 law enforcement officers died due to terrorist attacks.

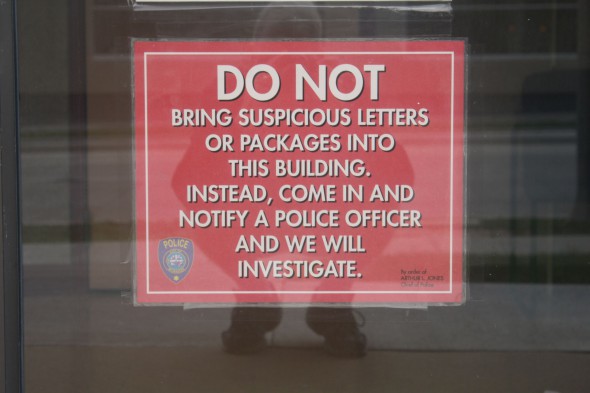

Most people know that they should not touch suspicious items. But if they do, a sign at the police building at 2620 W. Wisconsin Ave. warns, “Do not bring suspicious letters or packages into this building. Instead, come in and notify a police officer and we will investigate.”

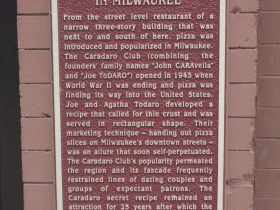

Broadway begins at its south end at the bridge over the Milwaukee River, and except for Catalano Square, runs north continuously to N. Water Street. A marker at Catalano Square tells us of the birth of pizza in the city in 1945, when the operators of the Caradaro Club began serving pizza at Broadway and Erie Street.

The Broadway Theatre Center, just north of the square, houses various theater and music companies. At least 14 buildings on the street in the Historic Third Ward are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Hilton Garden Inn stands at the site where the Newhall House stood, and a parking structure has replaced the former central police station where the anarchists’ bomb exploded. The north end of Broadway is dominated by former Blatz Brewing buildings and MSOE campus structures.

Carl Baehr, a Milwaukee native, is the author of Milwaukee Streets: the Stories Behind their Names, and articles on local history topics. He has done extensive research on the sinking of the steamship Lady Elgin, the Newhall House Fire, and the Third Ward Fire for his upcoming book, “Dreams and Disasters: A History of the Irish in Milwaukee.” Baehr, a professional genealogist and historical researcher, gives talks on these subjects and on researching Catholic sacramental records. He earned an MLIS from the UW-Milwaukee School of Information Studies.

Sites Along Broadway

City Streets

-

The Curious History of Cathedral Square

Sep 7th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

Sep 7th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

-

Gordon Place is Rich with Milwaukee History

May 25th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

May 25th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

-

11 Short Streets With Curious Names

Nov 17th, 2020 by Carl Baehr

Nov 17th, 2020 by Carl Baehr