The Artist as Rebel

Milwaukee Art Museum’s “Modern Rebels” is a wonderful if rather diffuse show.

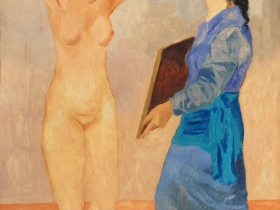

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). La Toilette, 1906. Oil on canvas. 59 1/2 x 39 inches (151.1 x 99.1 cm). Collection of Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. Fellows for Life Fund, 1926. © 2013 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Entering the Milwaukee Art Museum’s current exhibit, “Modern Rebels,” you’re hit immediately with “La Toilette,” the double portrait of the lovely Fernande Olivier, then the lover of the 25-year-old artist Pablo Picasso. Picasso is probably most famous in his early career for introducing Cubism into the modern vernacular, but this painting from 1906 predates the controversial Cubist masterpiece “Les Demoiselles d’ Avignon” by just one year. Still, he was already developing what would become the “PIcasso Style,” living with this lovely young woman and starting the lifelong practice of using his lovers and wives as models and muses.

There is little doubt, in short, that Picasso was one of the modern rebels of 20th century painting, and ample reason to include that work in this wonderful traveling exhibit featuring works from the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo. The work was purchased for the gallery in the 1920s by its board member A. Conger Goodyear, who was himself a rebel, with an appreciation of modernism not shared by all. His purchase of the Picasso so angered his fellow trustees that he was after voted off the board. Yet Goodyear remained active with the Buffalo museum even as he moved to New York to become the founding Board President of the Museum of Modern Art and his influence and donations help bring more 20th century art to the Albright-Knox Gallery.

This exhibition, whose full title is Van Gogh to Pollock: Modern Rebels, Masterworks From The Albright-Knox Gallery, gives viewers a dramatic sense of just how much great art was collected, with works by many of the big names of that last century or so, including artists not appreciated in their time: Van Gogh, Gauguin, Modigliani and Rousseau. A number of these works have frequently appeared as examples of the particular artist’s style, so it’s a rare opportunity to see the actual paintings rather than reproductions.

The rebellion in art that occurred beginning with the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874 was a direct challenge to the French Academy, whose emphasis on ancient classical art, the European tradition, and historical subjects rendered in an academic style, had held sway through the nineteenth century. Impressionism changed all that and was over the years succeeded by Post-Impression, Expressionism and a long list of isms, many represented in this show.

The result is a survey show of breadth not depth, a greatest hits of European and American Art. There are 68 artists and about 18-20 styles represented, depending on how you define them. It’s a great way to learn about art from the late 19th through 20th Century from excellent examples by the masters of the Modern. The curator Martha Jackson conceived of the show as presenting “the long curve” (also the title of the excellent catalog), referring to the learning curve inherent in the work, beginning with Post-Impressionism and moving all the way to Conceptual Art.

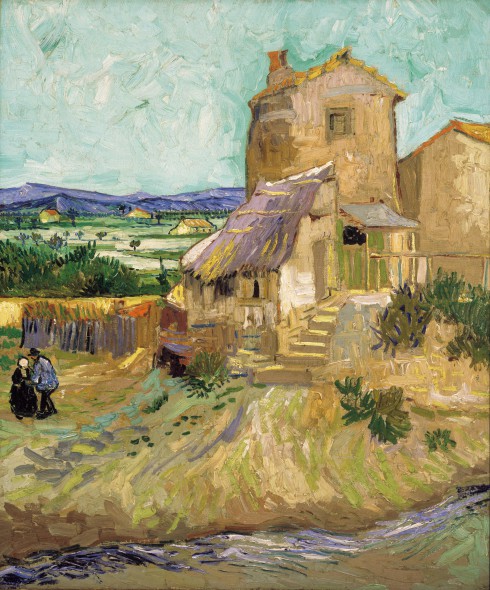

Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853-1890). Le Maison de la Crau (The Old Mill), 1888. Oil on Canvas. 25 ½ x 21 ¼ inches (64.8 x 54 cm). Bequest of A. Conger Goodyear, 1966.

The first section of the show features many of the stars of the “Paris School,” starting with the artist who has come to symbolize the rebellion of the late 19th Century, Vincent Van Gogh. “The Old Mill” has all the energy and delicacy Van Gogh is known for, with luscious thick yellows like butter cream frosting accented by a turquoise sky and subtle violets, all so chunky and rich you could lick the painting. Paul Gauguin’s “Spirit of the Dead Watching,” from his time in Tahiti, used the concept of a lurking spirit as a way to legitimize painting his 13 year old bride in the nude in a provocative pose. This section also features a “fauve” painting by Andre Derain, who works in a spontaneous fluid line, so that his whole little landscape seems like a dance of trees in glorious complementary colors. And the large multi-patterned painting of two women by Henri Matisse, influenced by the flattened compositions of Japanese art, still captures the opulent foliage and flowers of Provence.

We then move into the 20th Century and the beginnings of the “isms”: Surrealism, Cubism, Fauvism, Futurism, right before and into WWI. There is an exquisite self-portrait of Frida Kahlo with her pet monkey. Frida was considered outside the mainstream and appreciated by insiders for many years. Her fame increased considerably when feminists rediscovered her and she became a kind of saint for outspoken political, social and sexual beliefs and practices. Her painting is bold, yet delicate, the steamy tropical foliage and exotic pet perfectly complimenting her boldly direct self-portrait. Most people have only seen her work on all the Frida calendars and coffee mugs: it’s a real treat to see one of the original paintings.

These earlier paintings tend to use the exterior world as subject matter and then translated the outside world through the lens of the individual. After WWII the art world moved from Paris to New York City and the subject matter moves to the interior world. Abstract Expressionism, already in the works with Wassily Kandinsky, becomes the new style. It’s all about expression: Color as expression, brush strokes as expression, spilling it (literally) all over the canvas. Some practitioners are intuitive such as Jackson Pollock, known for “action” painting. Others appear spontaneous, but their work is actually planned and considered, not necessarily in the more traditional academic process of preliminary sketches, though Frans Kline and Willem De Kooning referenced sketches.

After World War II the rebellion of artists is not just about rejecting representational subject matter or supplanting the exterior world with the interior world of the artist, it’s at times a reaction to the gallery and museum system and its entanglement with money and success. Clifford Still is an example of an artist who rebelled from this kind of Capitalist co-option. This early Abstract Expressionist, whose large, dynamic work,

Clyfford Still (American, 1904–1980). 1957-D No. 1, 1957. Oil on canvas. Support: 113 x 159 inches (287 x 403.9 cm). Collection of Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. Gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr., 1959. © 2013 The Estate of Clyfford Still and The Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO.

“Exhibit 1957-D No. 1,” is represented here, despised the formal art world and would not sell to many museums or galleries. Yet, because this painting was purchased sight unseen by Seymour H. Knox, Jr. for the Albright Knox Gallery, a grateful Still later gave 31 of his paintings to the museum since it had shown the courage to commit to the development of one artist’s work without concerning itself with marketplace values of the art world.

The show moves on to the pre-minimalistic, connoisseur-appreciated work of Agnes Martin and Anne Truitt, their quietness contrasted to the loud Pop Art, such seminal works as the Andy Warhol Soup cans, and Roy Lichtenstein’s comics-inspired “Red and Yellow.” But as this survey show moves closer to today, it gets progressively more diffuse. Why do so many viewers just walk right through the later rooms in minutes after spending much longer looking at the previous works? By now Abstract Expressionism is more accepted, if nothing else because of its scale and the energy; viewers can respond to the dynamic quality of the brush strokes, the dramatic compositions and the vibrating colors. But there is less to unify the post-modern work and it can become a compendium of techniques, materials, philosophies — perhaps too much to absorb or even begin to appreciate in a single visit.

Personally, I like the Grace Hartigan work, and formally, I can see and appreciate the connections between Francis Pierce’s little plexi piece (luminescent and lovely) and Mark Rothko‘s orange and yellow painting. Still, while the later rooms represent many key innovations of the 20th century and while I appreciate them historically and perhaps even culturally, this is where a survey show like this starts to get dicey. The artists may still seek to challenge but the long curve of that rebellion, ism by ism by ism, begins to lose some of its punch.

Van Gogh to Pollock: Modern Rebels Masterworks from the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, runs through September 20 at the Milwaukee Art Museum.

Van Gogh to Pollock: Modern Rebels

Art

-

Winning Artists Works on Display

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

-

5 Huge Rainbow Arcs Coming To Downtown

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

-

Exhibit Tells Story of Vietnam War Resistors in the Military

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

I’ve seen this exhibition several times and this is a great article, Rose! Thank you!