Milwaukee’s Clean Water Advantage

Few cities have such control over their watershed, which gives Milwaukee an edge for cleanup efforts. Part II of series

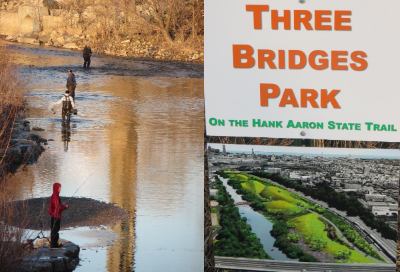

A largely inaccessible industrial wasteland just 20 years ago, the Menomonee River has been transformed into an extraordinary recreational asset, accessible by new bikeways and pedestrian bridges, and the new Three Bridges Park. The river is an important quality-of-life amenity for residents in adjoining neighborhoods and the entire metro area.

Back in 1925, this city took the first step in cleaning up its urban watershed with the creation of a wastewater treatment facility. Milwaukee was far ahead of most cities at the time, and has continued as a leader, which has had great benefits for the region. In Part I of this series we looked at the advantage of the city’s more protected and less-developed lakefront, and the benefit of its estuary and rivers being free of great flooding, compared to other cities. In this article we look at a third remarkable characteristic of Milwaukee’s freshwater landscape: the degree to which the environmental quality of Milwaukee’s urban rivers has been restored over the past 40 years. Although many impairments and water quality challenges remain (as reflected in water quality grades of C, C-, and D, respectively, given in 2012 by Milwaukee Riverkeeper to the Milwaukee, Kinnickinnic, and Menomonee River Watersheds), the scope of improvements achieved to date in the Milwaukee River is impressive compared to other major U.S. urban rivers. Furthermore, improvements to all three rivers appear to have gained momentum during the past decade in conjunction with the revitalization of the Menomonee Valley and the residential development boom that occurred along the Milwaukee River in the Downtown, Third Ward, and Fifth Ward neighborhoods. Milwaukee’s urban revitalization as a whole has been linked in multiple ways to the restoration of its freshwater resources.

History of Water Restoration Efforts

The beginning of Milwaukee’s water resource restoration efforts is subject to debate. However, an early milestone occurred in 1925 with completion of the initial wastewater treatment plant on Jones Island, which at the time was reported to be the largest and most advanced activated sludge wastewater treatment plant in the world. By 1940, Milwaukee ranked first among major U.S. cities in the proportion of residents in the metropolitan area (85 percent) served by a wastewater treatment plant. By comparison, 0 percent of the population of the Boston, Cincinnati, Detroit, Kansas City, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis metropolitan areas were served by a wastewater treatment system at this time. In these cities, raw sewerage and untreated industrial wastes continued to be discharged directly to area waterways.

By 1977, a settlement was reached with the State of Wisconsin to implement improvements that would reduce the number CSO events from 52 or more to less than 2 per year. Lawsuits with the State of Illinois continued through 1989, but ultimately ended with rulings in favor of Milwaukee. The settlement with the State of Wisconsin led to the completion of a $2.2 billion ($2.8 billion including interest) Water Pollution Abatement Program implemented by the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD) from 1977 through 1994.

The most significant project of the Abatement Program was the construction during 1985-1994 of the initial phase of Milwaukee’s Deep Tunnel System, which provided storage for up to 410 million gallons of contaminated storm water in massive bedrock tunnels bored approximately 300 feet beneath the ground surface. The system (which was expanded in 2002-2010 with the construction of two additional tunnels that increased the storage capacity to 521 million gallons) captures overflows from combined storm and sanitary sewers, storing the water for subsequent treatment, and thereby preventing water contaminated with bacteria, ammonia, and other contaminants from flowing directly into Milwaukee’s rivers and Lake Michigan.

Milwaukee’s CSO Control Efforts Vs. Other U.S. Cities

Although construction of the deep tunnel system has been a source of on-going debate and controversy (e.g., as demonstrated by the “Deep Tunnel Awards” given out by conservative talk show host Charlie Sykes), deep CSO storage tunnels have continued to be a component of nearly all water pollution abatement programs and systems engineered by other major cities, including systems in Indianapolis and Washington, D.C. that began construction within the past three years, and systems that are in the process of being designed for cities such as St. Louis, Honolulu, and New York City.

Indianapolis, with a reputation as one of the more progressive midwestern cities, began construction of its deep tunnel system in 2012, with a targeted completion date of 2026 (or 32 years after Milwaukee completed its initial system). In addition to the approximate $1.5 billion cost for implementing Indianapolis’ CSO plan, Indianapolis area residents are also facing an additional $2.5 billion in costs for other needed wastewater utility or waterworks system improvements.

48-inch lake sturgeon captured and released by WDNR personnel on April 22, 2014 (Earth Day). Thousands of metro-area residents have participated in activities focused on restoring this ancient species to the Milwaukee River. (WDNR staff photo)

The much earlier construction of Milwaukee’s CSO measures resulted in a significant financial benefit for area taxpayers in that nearly 47 percent of the $2.12 billion in costs for the initial system (excluding interest) was paid for through federal grants. (An additional $240 million in costs – or 11 percent — was funded through state appropriations). Federal support for CSO mitigation systems now being constructed in Indianapolis and other cities is available in the form of low-interest loans through the Clean Water State Revolving Loan Fund Program, but the full costs must ultimately be borne by local taxpayers.

The two, three, or even four decade head start by Milwaukee versus other major U.S. cities in implementing its water pollution abatement program has significantly impacted not only Milwaukee’s freshwater landscape, but also the areas that have been the focus for downtown revitalization during recent decades and the development of amenities such as the Milwaukee Riverwalk. The early head start also led to the growth and maturation of local environmental and water advocacy groups, earlier implementation of other types of environmental improvements (fish passage, green storm water infrastructure, etc.), and to some degree the city’s current business initiative centered on water-technology. While other cities with still degraded rivers have focused much of their development in areas away from their waterfronts, or relegated these areas to sports stadiums and expanded freeways, in Milwaukee these areas were recognized at an earlier date for their higher value for recreational and residential land uses. While cities throughout the U.S. have seen significant focus on waterfront areas, the development of Milwaukee’s waterfront areas is far advanced beyond that which has occurred in most other cities in large part due to having addressed CSOs decades earlier than these other cities.

Article Continues - Pages: 1 2

Freshwater Mecca

-

Milwaukee’s Extraordinary Freshwater Future

Feb 20th, 2015 by David Holmes

Feb 20th, 2015 by David Holmes

-

Milwaukee Leads Great Lakes Cities

Feb 13th, 2015 by David Holmes

Feb 13th, 2015 by David Holmes

-

Milwaukee’s Riverwalk Vs. San Antonio’s

Feb 4th, 2015 by David Holmes

Feb 4th, 2015 by David Holmes

Your reach of information and depth of passion continues. Let it flow!