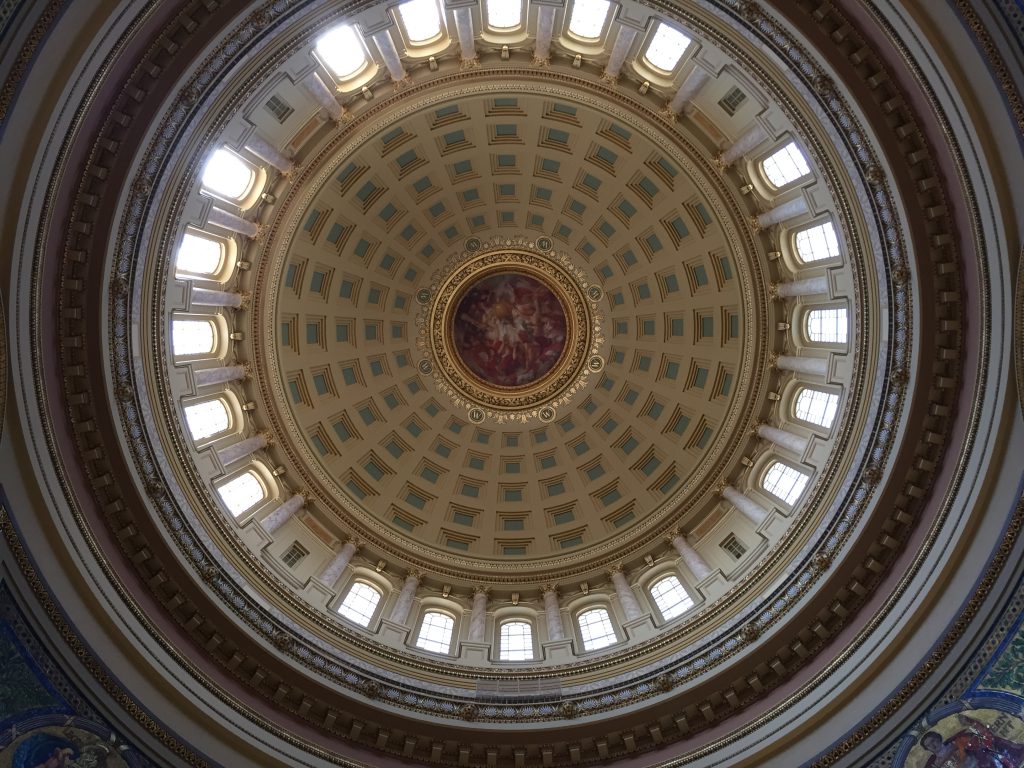

Wisconsin Public Pension System is 100% Funded

The fund, managed by the Department of Employee Trust Funds, is ranked among the best in the nation.

Bad news: The Social Security Trust Fund is on track to be wiped out by 2034.

More bad news: Unfunded state government pension liabilities in neighboring Illinois totaled $317 billion in mid-2020 – the worst in the nation when measured against a state’s gross domestic product, according to Moody Investors Service.

A National Association of Retirement Administrators survey ranked Wisconsin’s ETF and the retirement systems of South Dakota and Tennessee at or above 100% funded. SWIB celebrates its 70th anniversary this year.

In his first newsletter report, new ETF Secretary John Voelker discussed the agency’s impact: “Knowing that one plays a major role for up to 648,000 individuals’ quality of life is a sobering thought. More than 1,500 public employers rely on ETF for sustainable and quality employee benefits.”

When it was created in 1951, SWIB had three employees and managed $350 million. ETF administrators say its mission – invest in stocks – was then a “bold new approach.”

Today, SWIB has 230 employees and manages $144 billion in assets spread across what officials call a “diverse portfolio” that has benefitted from stock market gains.

In 2019, the last year for which audited figures are available, the Wisconsin Retirement System (WRS) had 215,070 retirees who received more than $5.6 billion in benefits.

The median annual retirement benefit was $21,923, or $1,826 per month.

Before SWIB was created, local governments and school districts had their own pension systems, according to a Legislative Fiscal Bureau report. Now, WRS represents 90% of all public employees. The city and county of Milwaukee have separate pension systems, however.

ETF’s newsletter noted how the system became law:

The idea that would lead to the creation of SWIB can be traced back to the late 1940s, when Gov. Oscar Rennebohm and State Treasurer John Soderegger began searching for a way to invest the state’s $30 million in idle cash balances. In 1951, union leaders John Lawton and Roy Kubista and attorney John Lobb were concerned about the struggle to generate adequate returns on the contributions made to the state’s public pensions. By building on Gov. Rennebohm’s and Treasurer Soderegger’s ideas, they dreamed of a state agency that could invest the assets of the state’s public pensions in new and innovative ways. Thanks to thoughtful state leadership and a committed Wisconsin Legislature, the investment board was born, and Gov. Walter Kohler signed SWIB into law as of June 28, 1951.

One of the biggest changes in WRS happened when Republican Gov. Scott Walker and Republican legislators passed Act 10 in 2011. It made public employees, except for those in police, firefighter or public safety unions, contribute more toward their pensions.

Before Act 10, most public employee unions negotiated contracts that had employers’ making all pension contributions.

The Fiscal Bureau summary documents a major shift in sources of pension contributions since Act 10: Contributions by public employees went from $11 million in 2010 to $965 million in 2019. Over that same period, contributions from state and local governments fell from $1.5 billion to $1 billion.

Now, ETF public employees’ and employers’ each contribute about 10% of retirement system income. The remaining 80% comes from gains on SWIB-managed investments.

For retirees with Core Fund investments, SWIB uses a five-year “smoothing” formula that considers investment gains and losses to determine future benefits. Earlier this year, ETF announced a 5.1% increase in Core Fund benefits.

After Act 10 became law, the number of public employees who retired almost doubled in a year – from 8,558 in 2010 to 15,352 in 2011.

There were 10,173 retirements in 2019, and 10,736 in 2020. Officials say up to 13,000 public employees – led by Baby Boomers – may retire in 2025.

In his 2021-23 budget request to the Legislature, Gov. Tony Evers asked for $741,000 to update ETF technology, which would include new cybersecurity protections.

The Legislature’s Joint Finance Committee has not yet acted on ETF’s budget.

Steven Walters has covered the Capitol since 1988 and receives an ETF annuity as a retired part-time journalism instructor at UW-Madison. Contact him at stevenscotwalters@gmail.com

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

The State of Politics

-

A Wisconsin Political Trivia Quiz

Dec 15th, 2025 by Steven Walters

Dec 15th, 2025 by Steven Walters

-

The Fight Over Wisconsin’s House Districts

Dec 8th, 2025 by Steven Walters

Dec 8th, 2025 by Steven Walters

-

The Battle Over On-Line Betting

Nov 24th, 2025 by Steven Walters

Nov 24th, 2025 by Steven Walters

The article omits one very important feature regarding the WRS post-retirement benefit structure. These increases can, and have been, “clawed back”, all the way back down to the original pension level, if investment performance so dictates. In effect, the post retirement benefit increases also serve as a reserve in the event of poor investment performance. This risk-sharing feature was the major reason WRS was able to climb back to the 100% funded level so quickly after the 2008-2009 meltdown.

The State Retirement system is an example of a well thought out government program that benefits hundreds of thousands of Wisconsin retirees. If this program needed to be established in today’s political environment, Republicans would be screaming “socialism” and would claim that somehow would be a violation of individual rights.

Mr. Nicolini doesn’t comment often, but when he does, I pay attention. He knows what he’s talking about.

His point about the WRS is a case in point. Thank you, Mark.