Reggie Moore’s ‘Blueprint for Peace’

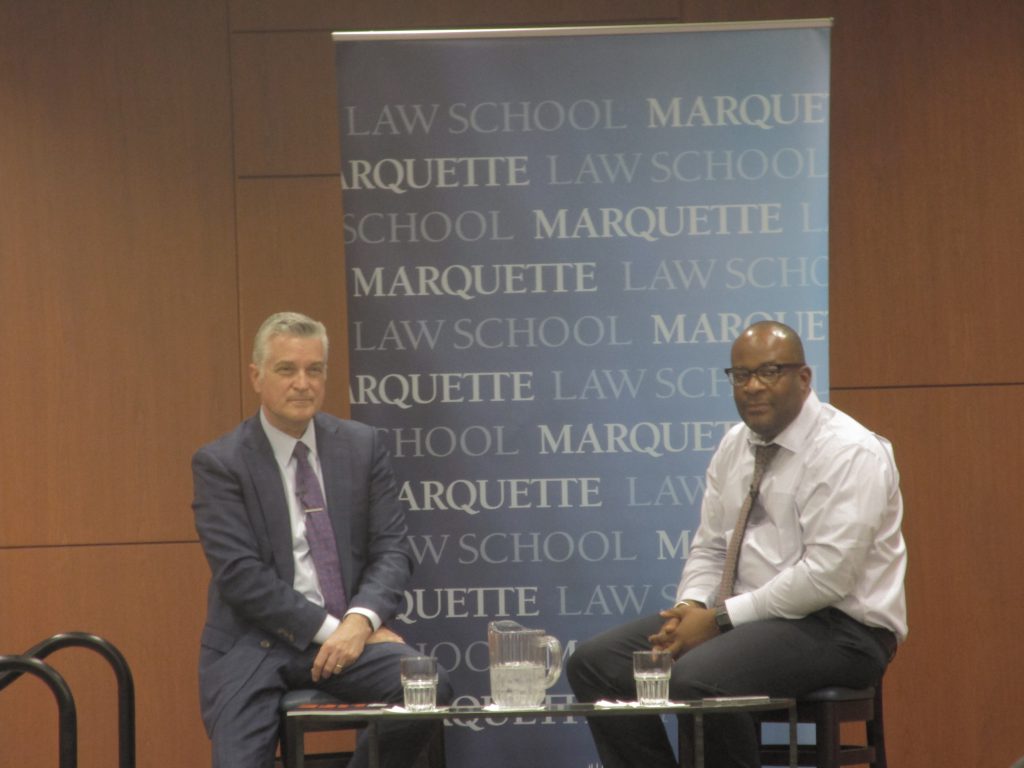

Head of Milwaukee’s Office of Violence Prevention talks trauma with journalist Mike Gousha.

When it comes to eradicating violence in Milwaukee, Reggie Moore, a local leader well versed on its detrimental impacts, has this to say: “I think there’s been progress, but we have a long way to go.”

The statement came seven hours after the Milwaukee Police Department Matthew Rittner became the third officer slain in the line of duty over the last eight months.

Moore, director of the Milwaukee Health Department’s Office of Violence Prevention, sat down with veteran journalist Mike Gousha Wednesday for the latter’s ongoing On the Issues series at Marquette Law School to discuss some of his efforts, including the multi-faceted Blueprint for Peace.

The conversation had been scheduled for weeks, but turned out to be timely as news began pouring out about what transpired on the city’s south side Wednesday.

Moore also settled into the role with first-hand experience, which he spoke of candidly Wednesday. One of his first brushes with violent behavior was at age 12, when he was held up at gunpoint.

“A child having a gun pointed in their face — it’s something you don’t forget,” Moore said.

In the years since, Moore began shepherding the Blueprint plan. It zeroes in on 10 neighborhoods and is wrapped around six goals.

But the overarching principle around Blueprint, Moore said, is remarkably simple: Violence is preventable.

Moore and other city officials have described Blueprint as Milwaukee’s first comprehensive violence prevention plan. Through partnerships and programs, the effort aims to reduce the number of shootings by first working to build a stronger, more resilient community.

“The pain that we hold inside — if it’s not transformed, it’s transferred,” Moore said. “We have to have places to heal.”

In addition to his leadership role in the Office of Violence Prevention, Moore more recently has been involved in a steering committee known as SWIM, which stands for Scaling Wellness in Milwaukee. Members in the collaborative have been working to address the impact of trauma in the city.

Moore said he is encouraged by SWIM, but prefaced the statement with this sentiment: “I think any initiative is as good as the momentum that is behind it.”

The concept of trauma was a recurring theme throughout the hour-long discussion. A trauma response initiative, for example, brings together the expertise of a cross-section of professionals in the community to work with families and children who have faced a traumatic event.

“It isn’t investigatory at all,” Moore said. “It is trying to address the impact.”

Comprehensive planning to deal with trauma, by Moore’s estimation, has been a long time in the making.

Gousha asked Moore to weigh in on the state of Sherman Park, which continues to heal two-and-a-half years after violence, unrest and arsons left visible scars within the neighborhood, shining a spotlight on some of the deeply rooted troubles blanketing Milwaukee.

Moore said he responded to Sherman Park the evening the unrest boiled over into the streets and witnessed, first-hand, the growing furor as afternoon gave way to evening on that historic day.

The situation started with bystanders wanting answers from law enforcement, Moore said, and verbal confrontations subsequently switched to physical acts.

“Everything pretty much escalated from that point,” Moore said. “It was a cumulative response, I think, to police accountability.”

The groundswell of support in the years since, including the unveiling of the Sherman Phoenix development, is a sign of the renewed optimism within that segment of the city.

“I think people are paying attention,” Moore said. “I think there’s been a level of momentum where folks are starting to stand up.”

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits, all detailed here.

I applaud the essential work Reggie Moore and the office of Violence Prevention is doing. However, I can’t help but think that focusing on the 10 neighborhoods can’t really address the full extent of the problem. Yes, there is a critical need to address the trauma and violence occurring on a daily basis in those neighborhoods. However, the violence in those 10 neighborhoods would not exist were it not for our racist housing, employment, urban renewal and judicial policies. The other neighborhoods, particularly those on the south side as well as white suburbs profited off the concentration of poor communities of color in these 10 overcrowded neighborhoods. It is long past time for the white residents of Milwaukee County to take personal responsibility for the conditions of the our neighbors in these 10 neighborhoods.