National Press Discovers Rural Wisconsin

Their observations, and demographic data, tell a story Democrats need to hear.

Can Democrats turn around their loss of rural and small town voters in Wisconsin and neighboring states? Perhaps a start is recognizing the convergence between many of the challenges facing cities such as Milwaukee and those responding to Donald Trump’s promises.

In past elections, Wisconsin has drawn the attention of the national press because as a prime example of the “big sort”— with Democrats increasingly concentrated in big cities and Republicans in suburbs. Over time, Milwaukee and Madison have become steadily more Democratic, while Milwaukee’s suburbs, the “WOW counties” (Waukesha, Ozaukee, and Washington) more Republican.

This year Wisconsin drew attention for the opposite reason—political changes in the less polarized, less populated areas of the state, particularly in the North and West. As I noted in a previous column, a substantial number of people who voted for Barack Obama in 2012 switched to Trump last November. Without these swings in voting (and similar swings in Michigan and Pennsylvania), Hillary Clinton would be president.

Here is a tour of low-population Wisconsin, courtesy of the national press. Let’s start with Juneau County, home of the largest swing to Trump.

Juneau County and the Sand Counties

In Juneau County, home to Mauston, Trump’s margin increased by 17.2 percent compared to Mitt Romney’s four years earlier. Despite this, it seems to have missed national press attention. A look at the Juneau County Star-Times makes it clear the county shares challenges with Milwaukee. A February 3 article describes the Mauston school district’s struggle to deal with homelessness. There is also an editorial (reprinted from the Wisconsin State Journal) lamenting the loss of farms and farmers.

Juneau County is one of Wisconsin’s “sand counties.” The attention these counties have received from the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel has mainly concentrated on high-capacity pumping of ground water for growing potatoes and other crops. This pumping has led the Little Plover River in Portage County to run dry in some summers.

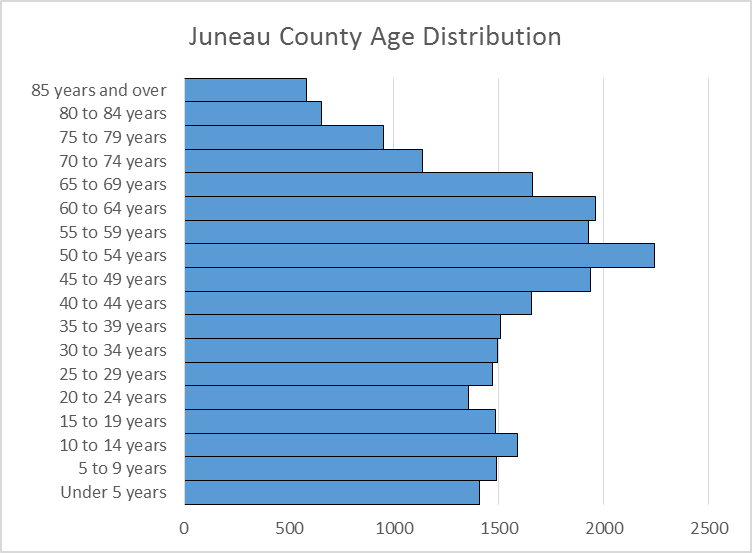

The graph shows the Juneau County age distribution:

This age distribution is typical of those for other counties with a swing to Trump, with two distinctive features. The population is considerably older than that of large city dwellers. The largest groups cluster between the late 40s to early 60s. Compare that distribution to Milwaukee’s, shown below.

A second feature is a gap in the early 20s. It is more prominent in other counties swinging to Trump. How much represents a permanent loss of young people looking for jobs elsewhere and how much due to a temporary move to attend college is unclear.

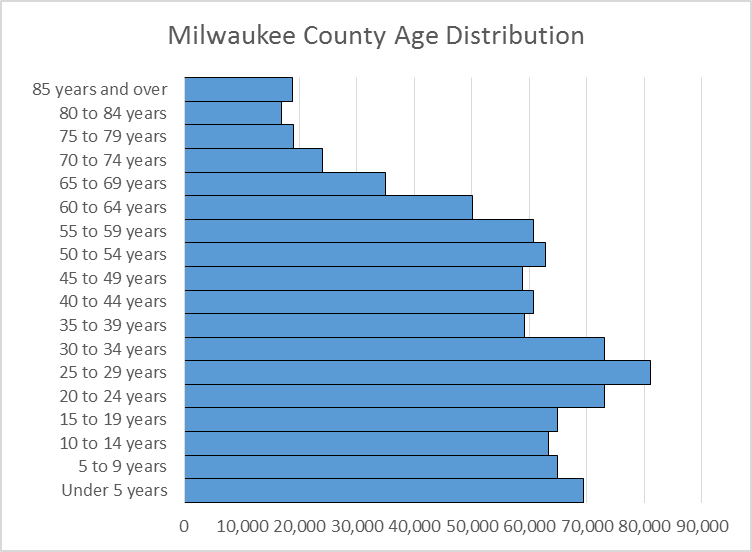

For contrast, here is the age distribution in Milwaukee County. The largest group are Millennials, not Baby Boomers.

Sawyer and Polk Counties

Both of these two North Woods counties had swings to Trump of 10 percent. The Washington Post’s David Weigel, in an article titled Rural Americans felt abandoned by Democrats in 2016, so they abandoned them back. Can the party fix it?, wrote about efforts by Democrats to turn things around in an area long represented by Democratic Congressman David Obey, but now dominated by Republicans. The article’s title is taken from a quote by a Democratic state representative who lost his seat: “And in the 2016 election, rural America abandoned Democrats, because they felt like Democrats had abandoned them.”

Kewaunee County

Kewaunee County, with a swing to Trump of 11.9 percent, breaks the rule that the swings occurred mainly in the North and West. It was the subject of several articles in the Journal Sentinel, describing pollution from concentrated dairy forms. The most recent example was titled One-third of wells in Kewaunee County unsafe for drinking water.

Sauk County

A swing to Trump of 9.5 percent resulted in a virtually tied vote in Sauk County, home to Reedsburg and Baraboo. It also resulted in a New York Times article: In Divided Wisconsin County, Packers Talk is O.K., but No Politics, describing the strains of such a polarized county, with each side blaming the other.

Crawford County:

Crawford County, with a 13 percent swing to Trump, generated the national story that does the most to dig out the reasons for Trump’s ability to pick up Obama voters. An article by Associated Press’s Claire Galofaro entitled In a pro-Trump Wisconsin county, voters await a promised economic revival explores why so many counties along the Mississippi River switched to Trump.

It starts:

She tugged 13 envelopes from a cabinet above the stove, each one labeled with a different debt: the house payment, the student loans, the vacuum cleaner she bought on credit.

Lydia Holt and her husband tuck money into these envelopes with each paycheck to whittle away at what they owe. They both earn about $10 an hour and, with two kids, there are usually some they can’t fill. She did the math; at this rate, they’ll be paying these same bills for 87 years.

It describes others in Prairie du Chien who are just getting by:

Among them is a woman who works for $10.50 an hour in a sewing factory, who still admires Obama, bristles at Trump’s bluster, but can’t afford health insurance. And the dairy farmer who thinks Trump is a jerk — “somebody needs to get some Gorilla Glue and glue his lips shut” — but has watched his profits plummet and was willing to take the risk.

According to Galofaro

There are plenty of jobs in retail or on factory floors, but it’s hard to find one that pays more than $12 an hour. Ambitious young people leave and don’t come back. Rural schools are dwindling, and with them a sense of pride and purpose.

Of the articles about the swing to Trump in small-town and rural Wisconsin, Galofaro’s offers the most in-depth examination of the concerns driving the swing. Keeping in mind the caveat that anecdote is not data, her article suggests that, at least in Crawford County, the underlying problem is not so much a lack of jobs. Instead, people with jobs are feeling that low pay keeps them from ever getting ahead.

The 2016 election shows that these voters are in play. At some point, Trump will need to demonstrate that his policies will help them. While it is very early in his administration, his cabinet picks don’t reflect a priority for the concerns of people in Crawford County and the other low-population Wisconsin counties. If anything, the priority of those chosen for the Trump administration is keeping pay low.

This represents an opportunity for Democrats. I suggest that an effective response should include the following:

- A substantial expansion of the earned income tax credit and the minimum wage

- Prioritize differentiation strategies rather than a low-cost strategy

- Protect the environment; avoid the temptation to attract businesses by shortchanging the environment

- Expand the Obamacare subsidies so that rates are not dependent on the health of the pool

- And, of course, make sure there are jobs for anyone wanting to work

I plan to explore these policies in a future column. If well designed, they can benefit both Crawford and Milwaukee counties.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Interesting article. What is a differentiation strategy, and how is it an alternative to a low-cost strategy? Come to think of it, what do you mean by a low-cost strategy? Honest question – just need more info to understand.

4 of the 5 policies listed were promoted by Democrats throughout the 2016 campaign, but it appears that rural WI voters didn’t hear them. Could these voters have failed to hear messages in their interests due to despair over a stagnant economy in rural WI, or were the voices of the Dems drowned out by the seemingly intentionally confusing messages of the hard right?