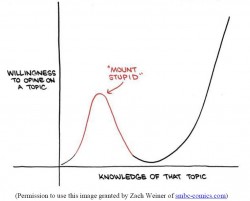

Mount Stupid

How an “expert” learned some lessons about black culture and good food.

I’ve stood atop Mount Stupid many times, but my most profound encounter with it was about eight years ago. I was two years into my time at the helm of a new nonprofit organization, hell bent on improving fresh fruit and vegetable access and reducing obesity in Milwaukee’s north side neighborhoods – the kind of place that many from outside the community call a “food desert.”

I’d received a grant to run healthy cooking demonstrations at a food bank in my agency’s predominantly African American neighborhood. I was dicing some onions to prepare for the demonstration. It was springtime, and so the onions had been in storage for months and were especially concentrated and pungent that day. A woman who was standing in line to get her food basket took one look at my tear-streaked face and told me, “You’re doing it wrong.”

I handed her the knife and stepped back. She took a whole onion and deftly halved it lengthwise. Then she took the tough outer layer and peeled to back towards the root end, taking care not to tear it off. “Use the skin as your handle,” she said, “so that you won’t cut yourself if your knife is dull, and you will use the whole onion, and since your hand is out of the way you can chop faster and you won’t cry so much.” The rest of the feedback from the food bank clients was positive but still disconcerting, ranging from “I would add more garlic” or “if you put in some other spices you would need less salt.”

The next morning an uncomfortable question started bouncing around in my head: “Just who is helping whom?” I began my descent down the other side of Mount Stupid. As someone who was trying to present himself as an authority on food deserts, it was an uncomfortable place to be. I realized that my solution was aimed at a stereotype and that my show-and-tell agenda had no space for a conversation.

Even now, forty years later, this historic link between early Milwaukee restaurants and the African American community has created the most food-opinionated culture that I’ve ever encountered. Being called a good cook is a point of pride. One time I asked a lady for a recipe and she gave it to me, begrudgingly and slowly, as if she was doling out hundred dollar bills. But when I made it at home it didn’t taste the same and I told her so the next time I saw her. She replied, with a sly smile: “That’s ‘cause I left out the secret ingredient, and if I tell you I’ll have to kill you.” Last year I met a grandmother who told me that she was planning to give her recipe collection to just one of her three children because she’d determined that the other two lacked the culinary talent.

As I learned the neighborhood histories and aspirations that I’d missed the first time around, I began to see people, not stereotypes. I saw people who were painfully aware of all the doctoral dissertations that had been minted off of the neighborhood’s struggles. The folks were tired of being poked, focus grouped, studied, and labeled as problems. They were tired of the knuckleheads who make up 1% of the population making 100% of the news coming out of the neighborhood.

Just as most White Fish Bay residents don’t like it when outsiders take an un-nuanced approach by calling their city a collection of racists, many north side Milwaukeeans don’t take kindly to the “Food Desert” label either. It’s a judgmental and one-dimensional term that implies a barren landscape where nothing will grow. It’s a word that does not invite further investigation. It implies the need for a solution that is imposed on people and not with people.

Like a lot of Midwestern cities, Milwaukee has its problems when it comes to food. But I also see potential. In future columns I will write more about some of the healthy foodies that I’ve gotten to know.

Urban Foodie Question of the Week:

A reader responded to last week’s query about banana-and-mayo sandwiches by telling me that her Milwaukee family eats peanut butter and pickle sandwiches. Really? What kinds of pickles? Kosher dills? Gherkins? Someone please tell me before I try this myself.

Urban Foodie

-

The Junk Food Debate

May 14th, 2013 by Young Kim

May 14th, 2013 by Young Kim

-

Tips for Twenty-Somethings

Mar 15th, 2013 by Young Kim

Mar 15th, 2013 by Young Kim

-

Why Hmong-Grown Produce is Different?

Dec 5th, 2012 by Young Kim

Dec 5th, 2012 by Young Kim

I mean to contribute to the foodie question of the week. Growing up I would eat white bread sandwiches with sliced (dill) pickles, creamy peanut butter, and lays potato chips. I’ve had cream cheese ones instead of peanut butter, but I recall peanut butter being much better. I also recall eating peanut butter and bologna sandwiches. I stopped eating all three around the age of 10 or so. That wasn’t the typical sandwich for me, just something to eat during the summer or weekends sometimes.

My father mentions eating cheese and jelly sandwiches when he was growing up. I’m sure that tasted as bad as it sounds, but he didn’t seem to think that he or any of his siblings took issue with said sandwich.

I just had a pickled daikon sandwich for lunch. The pickled daikon is Korean, actually. Just put them between buttered slices of bread and hope they don’t fall out when you bite into it.

I’m Milwaukee born and raised and can’t say that I’ve had either the banana and mayo or the peanut butter and pickle sandwiches. Instead, I grew up eating banana-Miracle Whip-peanut butter sandwiches. My dad would pack our school lunches on the days we chose to forego the hot lunch, and this was one of our favorites. I don’t know where this came from, but the Great Depression claim intrigued me since many of the favorite foods that come from my dad’s side of the family are born out of my grandparent’s depression-era mindset coupled with the fact that they had six kids to feed. Cheap, economical food that went a long way was the rule. I’ll have to ask Dad his thoughts on the origin.

I occasionally make this sandwich for myself now, and it’s as delish as I remember from my childhood. The Miracle Whip is key, since it’s got the tanginess that sets it apart from mayo and complements the sweetness of the banana and peanut butter just perfectly. It’s moisture also keeps the sandwich from being too dry and chewy. I like to use wheat or whole grain bread for additional flavor.

The only way I have found to cut onions so my eyes do not tear up is to use a scuba diving mask and snorkel. It looks very strange indeed, but I seem very sensitive to cutting onions and I never cut onions without a mask and snorkel.

no other culinary technique is as effective in preventing the tears that arise from cutting onions.

Get over feeling silly and put on the diving mask and snorkel.

no other technique is as effective

and I learned the trick from a french chef.

@Paul – Try a holding a piece of stale bread in your mouth. The underside catches all of the onion fumes. – Young