Do You Believe in Beavers?

Study finds return of beaver dams to Milwaukee watershed could add $3.3 billion worth of stormwater storage.

Conservation professionals from different entities and parts of the state worked together to build and document multiple BDAs at Briggs Wetland. They will revisit the site to observe changes over time and use what they learn to inform other projects appropriate for hands-on nature-based practices. Photo courtesy U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

In November 2020, as the country battled a global pandemic, a study on a quite different topic was quietly published online. The 162-page report by six researchers from UW-Milwaukee and two from Milwaukee Riverkeeper identified 14 sites in the Milwaukee River Basin that posed prime targets for restoring beaver habitat.

Why beavers?

Why Milwaukee?

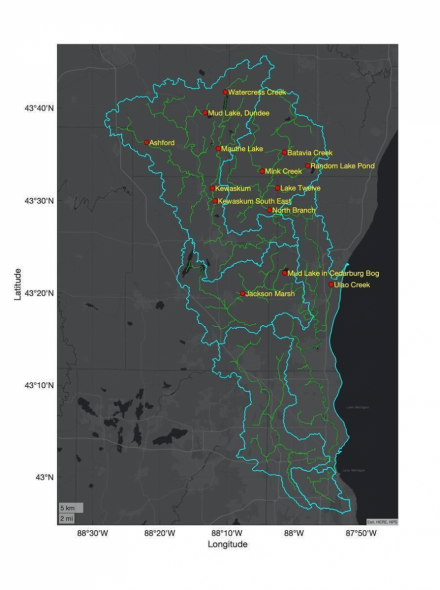

Figure 4.14 Locations of 14 recommended beaver restoration sites from page 84 of report. Source: MMSD Contract P-2890 “Project: Hydrological Impact of Beaver Habitat Restoration in the Milwaukee River Watershed,” November 2020.

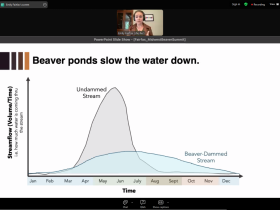

The potential benefits calculated were hydrological: 1.7 billion gallons of stormwater storage valued at $3.3 billion — almost twice the city’s annual budget. Stormwater is stored because beaver dams and the wetlands they “engineer” slow down and spread out water.

Modeling showed that reintroducing beaver wetlands upstream in the watershed — many on Milwaukee River tributaries in Ozaukee County — could reduce peak storm flows and remove 500 properties from the floodplain downstream in Milwaukee County.

For these benefits and others, the nonprofit Superior Bio-Conservancy — led by Bob Boucher, who also founded Milwaukee Riverkeeper — advocated a 900-square-mile “recovery zone” for beavers and other aquatic mammals in the Milwaukee River watershed.

We wondered about follow-up since 2020: Was anyone piloting beaver projects in the Milwaukee River Basin?

“This [2020 report] was funded by MMSD as a research project to identify possible downstream flood reductions by reintroducing beaver to the Milwaukee watershed,” wrote MMSD’s executive director Kevin Shafer in September 2024 in response to our inquiry. “Due to limited resources, MMSD has not implemented any recommendations at this time.”

Boucher pointed to the state’s policies as a barrier to beaver projects. Wisconsin sets no bag limits during winterlong beaver hunting and trapping seasons, requires neither permits nor limits to landowners removing beavers deemed a nuisance, and does not require individuals to report a beaver harvest.

In August 2023, Boucher’s group filed a lawsuit over Wisconsin’s beaver policy. They argued it was time to incorporate the latest science into the Environmental Assessment (EA) — last updated in 2013 — informing the state’s beaver management plan. The lawsuit included myriad references suggesting the many benefits beavers offer as “ecosystem engineers” and “keystone species” — slowing down flows, recharging groundwater, adding habitat for other species, and providing refuge for wildlife from wildfires.

The lawsuit was filed against the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for “Killing 28,141 Beavers, 1,091 River Otters, and Destroying 14,796 Beaver Dams in 10 Years Funded by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.”

The USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services, or APHIS, has a contract with WDNR to lethally manage the state’s beaver population with an estimated $500,000 annual cost.

Late in 2023, USDA announced it would review the EA for Wisconsin. An update may be available in November 2024, according to Dan Hirchert, USDA APHIS state director.

Meantime, momentum is building among so-called “beaver believers.” The self-applied term refers to a loosely affiliated network of environmental practitioners and advocates embracing beaver coexistence strategies.

On Aug. 28, 2024, 1,200 people logged onto Zoom for the second annual Midwest Beaver Summit, maxing out the event’s virtual capacity. Hosted by the Superior Bio-Conservancy and Illinois Beaver Alliance, it featured a range of speakers, with a keynote address by Dr. Emily Fairfax from the University of Minnesota.

In an interview, Fairfax called the 2020 MMSD report “really significant.”

She said beaver flood mitigation is understudied, but where it has been in the U.K. and Canada, “they’re finding absolutely incredible” reductions in flood waves by beaver ponds: “huge storms, hundred-year storms, hitting [beaver] complexes and barely breaching any of them.” Flood waves that do pass downstream are less powerful, she said.

Fairfax stressed the need for more research to support 21st-century beaver policy across the Midwest.

“There’s just very little data in [Wisconsin] on what beavers are doing, what they’re not doing, what their historical distribution was, what is their relationship to fish,” Fairfax said.

When it comes to managing Wisconsin’s cold water streams for trout, beavers elicit polarizing viewpoints.

“The big challenge and the hurdle there is just this idea that the fish folks believe beaver dams and beaver dam analogs are impediments to fish mobility and fish passage” and cause “potential thermal negative impacts to cold water fisheries,” said Clay Frazer, who leads the Madison-based environmental restoration firm Native Range Ecological.

Clay Frazer poses with Daniel Fuhs during the installation of a pond leveler for a private land owner in Columbia County, Wis. in October 2023. Photo courtesy of Clay Frazer.

Those inferences are based on one WDNR fisheries study published in 2002, which has been widely criticized by beaver believers who point to newer research that suggests more complex relationships.

WDNR is currently amid a new statewide study, started in July 2018 and running through June 2026, to gather updated data on how beavers influence cold water stream habitat and trout populations in Wisconsin.

According to WDNR’s principal researcher Dr. Matthew Mitro, the study spans 48 trout streams across the state, 23 where beaver control was removed (with beavers building dams on 18), paired with 24 control streams (18 of those without beaver dams).

Data were not yet publicly available.

In response to emailed questions, a WDNR spokesperson summarized the state’s current policy: “Trout stream protection takes precedent over protection of beaver on high-quality trout streams. Reduced beaver population has occurred. Maintenance of a stable beaver population is desired.”

For many beaver believers, current state policy is detrimental and the new WDNR study does not go far enough.

“It’s not a bad study, it’s just a very myopic study,” said Courtney Dean, PSM Conservation Biology graduate student at UW-Stout speaking at the August 2024 summit. “And the concern is that this limited-scope study is going to be informing beaver policy for the next 10, 20, 50 years here in the state.”

While beavers are provoking policy conflict, they are also inspiring local cooperation — and providing a reminder that beaver and trout, two species that co-evolved for millennia, can coexist.

In September 2024, a few dozen conservation professionals gathered to participate in a “beaver dam analog” workshop just outside Beloit, Wis.

Organized by Mike Engel, a Madison-based biologist with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the collaborative learning exercise followed over a year of prep work and trust-building.

At the Briggs Wetland, a 24-acre site owned and managed by nonprofit The Prairie Enthusiasts, it’s just a short muddy hike to the East Branch of the Raccoon River, where beavers have already built dams on a stream recognized for its native brook trout.

Briggs Wetland was historically a sedge meadow. Later, ditches were dug to drain artesian springs to dry out the spongy land for cattle grazing. Engel thought this made the site ideal: To improve the ecology, they could modify the ditch that feeds the river, but without using heavy machinery that could disrupt the wetland.

October 2024 construction photos of Jim Hoffman BDAs in Alma Center, Wis. similar to those more common to the Western and Eastern United States. BDAs are less common to Wisconsin but Native Range Ecological is among those with recent installations. Frazer hopes that projects like these can help streamline the WDNR permitting process. Photo courtesy of Clay Frazer.

Building “beaver dam analogs” or “BDAs” takes a lesson from “nature’s engineers”: teams of humans pounded wooden posts into banks and weaved willow stakes across in an effort to slow flow, trap sediment, and encourage water to enter the ground.

“Even though we’re in a rural area, the same principle applies,” Engel said. “We don’t necessarily want that spring water going immediately to the trout stream. What we’d like for it to do is saturate the ground and slowly trickle and be filtered in before it gets to the trout stream.”

In September, Engel’s assembled teams built multiple BDAs and will return to observe how the site responds over time. The hands-on learning opportunity was intended to provide natural resource managers with BDA familiarity and model how to engage youth and the public in nature-inspired land stewardship.

BDAs like those at Briggs Wetland and “flow devices” such as “pond levelers” — structures placed in streams to allow beavers to build dams but keep water flowing to avoid damaging human infrastructure — are fairly simple structures, but complicated to permit.

Better known in other states, Wisconsin’s permitting process has slowed their adoption in this state.

BDAs and flow devices require monitoring and maintenance, said Frazer, the environmental restoration professional, but are relatively inexpensive to build and deploy. However, the time and money it takes to navigate a lengthy permitting process discourages many property owners.

Frazer is working on several Wisconsin projects with motivated property owners and WDNR to streamline the permitting process.

In what beaver believers call “ecological amnesia,” we often forget that Milwaukee’s very existence owes itself to the fur trade — fur extracted from a teeming population of beavers, which hundreds of years ago were far more enmeshed with the story of our waters.

Beavers remain prevalent throughout the state, though population estimates are uncertain. To gain a current snapshot of the Milwaukee River Basin, Reflo invited Dr. Fairfax to use the methodology her lab has used to document beaver dams in other regions. Reviewing aerial images available through Google Earth, she identified 19 probable beaver dams in the Milwaukee River Basin — including two Ozaukee County clusters in areas that the 2020 report recommended would make good beaver wetlands.

It seems beavers agree with Milwaukee’s hydrological modelers. They have colonized prime semi-aquatic real estate on their own.

Boucher, whose nonprofit is based from his River Hills home, believes the entire Great Lakes region needs “a critical pivot” in beaver policy — especially in the face of climate change.

“If we want to protect our water, protect our wildlife, and protect ourselves,” Boucher said, “the cheapest, fastest solution that we can do to this country’s waterways is to embrace — and actually incentivize, especially on rural lands and wetlands — having millions more beavers.”

Slides from the Midwest Beaver Summit

Photos from Ducks Unlimited

Photos from U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

Writer Michael Timm is a Milwaukee Water Storyteller for the nonprofit Reflo.

This project is funded by the Wisconsin Department of Administration, Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the terms and conditions of Wisconsin Coastal Management Program Grant Agreement No. AD239125-024.21. Funded by the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office for Coastal Management under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant # NA22NOS4190085

To paraphrase the Cowardly Lion from The Wizard of Oz:

“I do believe in beavers. I do, I do, I do, I do.”

Please keep us informed of any progress in the development of these “beaver-inhanced” wetlands. It is working so well

in some areas. If we can get over the “trapping only” mentality, we can use this practical and doable solution in our efforts to

combat the effects of climate change.