Milwaukee’s Green Schoolyards Gain National Attention

Seattle and other cities learning from Milwaukee's 'incredibly inspiring' work.

Visitors at Kluge Elementary consider the giant bioswale cut into the middle of an asphalt expanse as part of the Children & Nature Network annual conference, which drew participants from across the U.S. to tour three Milwaukee schoolyards. Photo by Michael Timm.

Milwaukee is quietly leading the nation with an innovative model changing what it means to grow up in a 21st-century American city.

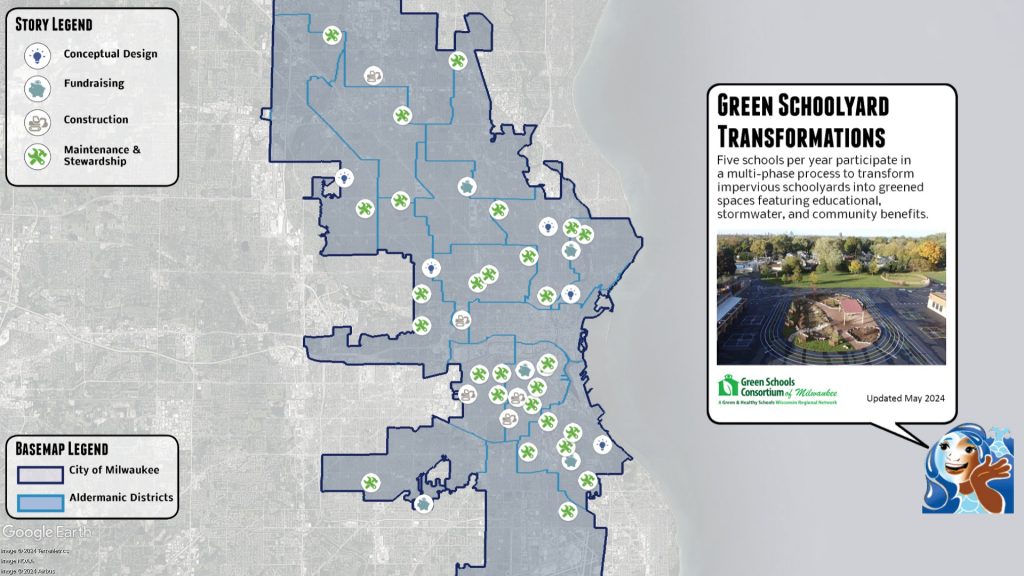

Since 2019, Wisconsin’s largest school district and its partners have transformed 26 schoolyards, replacing 17 acres of asphalt with educational green spaces that manage water where it falls and provide park-like community gathering spots in 14 of the city’s 15 aldermanic districts.

The area of asphalt removed so far is equivalent to the combined footprint of the Fiserv Forum, the Deer District, and the vacant lot where the Bradley Center once stood.

Thousands of students are impacted daily by rejuvenated surroundings, attracting public health researchers to quantify the benefits of these urban oases.

Five new schools are slated — and funded — to construct their “green and healthy” schoolyards during summer 2024. Another five schools are already raising funds for 2025, and five more are drawing up community-based conceptual designs for construction in 2026.

MPS schools involved in Green & Healthy Schoolyard redevelopment shown over a map of Milwaukee aldermanic districts. The schools are located in 14 of 15 districts. Icons show 4 phases: Conceptual Design, Fundraising, and Construction, which each span one year. Maintenance & Stewardship is ongoing afterwards. Image generated from Milwaukee Community Map. Image courtesy Reflo.

Every fall, over a dozen of the Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) apply to join the multi-year process currently with capacity to add five new schools per year.

With 41 of MPS’s 156 school properties (26%) now in a community-supported process touted as a local success, advocates are calling to find resources to double the pace from five schools per year to ten.

Milwaukee’s leadership attracted delegates from a dozen cities on May 28, 2024 as part of the Children & Nature Network’s annual conference, held this year in nearby Madison.

Over 40 guests toured three MPS schoolyards across the city — at the Clement Avenue, German Immersion, and Richard Kluge schools.

The green spaces were a striking contrast with traditional asphalt-and-chain-link schoolyards. Bioswales — vegetated depressions engineered to manage water — are cut into the ground in kidney-bean curves. Visitors browsed verdant native plants soaking up water and attracting bees and butterflies, observed children using nature-based play structures hewn from black locust logs, and gathered beneath shade structures to learn about MPS’s climate curricular alignments.

For many who had never visited Milwaukee, it was an excellent first impression.

Delegates from a dozen U.S. cities tour Kluge Elementary schoolyard on May 28, 2024 co-led by Justin Hegarty, executive director of the nonprofit Reflo, and Heather Dietzel, sustainability project manager for MPS. Photo by Michael Timm.

How has Milwaukee made the magic happen?

Beyond philanthropic support, two key factors are widely credited: the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD)’s investment in green stormwater infrastructure and the catalytic work of the Milwaukee nonprofit Reflo, which connects the school district to partners and resources to support long-term success.

MMSD has set the framework for collaboration and injects public dollars into the projects. But multiple observers said Milwaukee’s “secret sauce” is the nonprofit Reflo, a nine-person team led by environmental engineer Justin Hegarty.

Incorporated in 2013, the organization (pronounced “Re-flow”) evolved from building rainwater harvesting systems for urban agriculture to its emphasis on greening schoolyards.

Reflo has repeatedly won the MMSD-issued contract to support conceptual design projects for MPS, working hand in hand with individual school communities. In a phased process, Reflo then supports fundraising efforts and coordinates with contractors-and-facilities staff.

The nimble group also helps schools maintain their green infrastructure. Reflo works with MPS to host summer high school internships. Interns pull weeds, maintain trails, and learn about jobs that sustain these vital spaces.

Milwaukee’s work — and its emphasis on partnerships — offers lessons for cities across the country.

In 2021, the Children & Nature Network hosted a peer learning exchange with teams from 11 cities. Milwaukee’s team included MPS, Reflo, City of Milwaukee, and MMSD representatives.

“In many ways Milwaukee is where a lot of teams would like to be,” said Mikaela Randolph, then-green schoolyards technical consultant for the Children & Nature Network. “It’d be great [for other communities] to have a school selection process that feels open and transparent. It’d be great to have a healthy and green schools consortium that has a one-day conference on an annual basis. Because what those types of activities do is amplify that this work is really important.”

Cameron Steinback, program manager for Seattle-based nonprofit Earth Gen, whose work is similar to Reflo’s, toured Milwaukee as part of the 2021 peer learning exchange. He said Seattle is learning from Milwaukee how to take a comprehensive approach to ensure its outdoor environmental learning spaces prioritize community needs. He said Milwaukee should be proud of its “incredibly inspiring” work, saying its people “have done such an excellent job and they’re actually ahead of the curve.”

In 2022, voters in the City of Austin, Texas, approved a $2.4 billion bond to modernize 26 of its 130 schools over five years, said Colleen Garland, Austin’s outdoor learning specialist, including shade tree planting, green stormwater infrastructure, and outdoor learning spaces.

Garland’s colleague Yasmine Anderson, who coordinates Austin’s Cities Connecting Children to Nature program, said Austin is missing an entity like Reflo to help hold collaborations together and support long-term community stewardship. “We’re missing that piece,” she said. “We’re still at the evolution phase.”

Representatives from other cities noted other inspirations from Milwaukee’s model. The cohesion of Milwaukee’s partner relationships impressed Sprinavasa Brown, co-founder and executive director of ELSO, a nonprofit based in Portland, Ore. “I think that’s the key part,” she said.

Public use of Milwaukee’s schoolyards beyond school hours impressed Jac Kyle, who works with the Detroit Recreation Department. “I love the fact that these are open after hours — that increased access,” Kyle said.

Physical accessibility impressed Ingrid Kanics of Kanics Inclusive Design Services based in North Carolina, who toured Milwaukee’s green schoolyards in a wheelchair. “You can do nature play and accessibility,” Kanics said. “You just need to be really intentional about it.”

Outdoor learning opportunities on display at Milwaukee’s German Immersion School impressed Sheldon Cox, director of career and technical education at Rochester City School District. “It gives me a different perception to expand learning beyond the four walls of the classroom,” Cox said.

Aerial view of German Immersion School in 2020, before Green & Healthy Schoolyard redevelopment. Photo courtesy Reflo | WCMP did not fund the drone photography.

Ninety miles to the south, Chicago is also greening schoolyards at a similar scale and pace, though Chicago’s population is almost five times Milwaukee’s.

Chicago has a different funding model, said Claire Marcy with Healthy Schools Campaign, who manages Chicago’s Space to Grow program in partnership with the regional nonprofit Openlands.

Marcy said dedicated capital funding flows from three partner agencies: Chicago Public Schools, the Department of Water Management, and the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District — under an EPA consent decree to build green stormwater infrastructure to help manage flood risk.

So far Chicago has upgraded 34 schoolyards, with three more in design in 2024. Looking ahead, Marcy said Chicago can count on a $48 million commitment from the three public agencies for its second phase.

Scrappy Milwaukee raised its own funds — with Reflo taking an active role in fundraising.

As of 2024, MMSD’s Green Solutions (with the City of Milwaukee Department of Public Works) and Green Infrastructure Partnership Project dollars accounted for 39% of total program costs, with 23% from federal grants, 22% from private foundations, 12% from school fundraisers/budgets, and 4% from state grants, according to Reflo.

Aerial view of German Immersion School after Green & Healthy Schoolyard construction completed in 2023. $1,700,318 was raised for the project; 63,437 sq. ft. of asphalt were removed; 238,151 gallons of stormwater per rain event are now captured. Photo courtesy Reflo | WCMP did not fund the drone photography.

Dollars from the Fund for Lake Michigan, a private foundation and long-term partner, accounted for about 2% overall, but helped provide funding flexibility and strategic partnership critical to success. “Private philanthropy helps us connect the dots and allows us to integrate STEAM curricular connections and build the more socially-connected improvements like the community gathering spaces, recreational facilities, and outdoor classrooms” Hegarty said. STEAM stands for science, technology, engineering, art, and math.

With neither mandate nor guarantee, MPS and its partners raised over $28 million from diverse sources.

“Each of our funding sources is identifying the things that are important to them,” said Heather Dietzel, MPS Facilities and Maintenance sustainability project manager. “So, what Justin and I and Reflo do is piece together everything so we can have a comprehensive program.”

In aging cities facing stormwater challenges, managing water motivates public partners. But the benefits of greener schoolyards extend beyond stormwater management.

Perceived benefits of outdoor learning at schools include enhanced mental health and wellbeing, a deeper connection to nature, physical and socio-emotional development, and physical health, according to over 550 respondents to a nationwide survey of schools conducted by Luke Parker, a doctoral student at University of Kansas.

Health researchers in Milwaukee are leading the way in helping quantify benefits — like improved physical and socioemotional health of young people — that could attract new partners motivated by health equity.

The Medical College of Wisconsin is one of the partners measuring the impact of greening schoolyards. Jean Bikomeye, a recent doctoral student doing such research, said Milwaukee has “decoded the code” for how to leverage partnerships at the intersection of climate resilience, environmental justice, and health equity. “I think the work in Milwaukee — it’s unique across the country,” said Bikomeye.

Reflo sponsors the eighth annual Green & Healthy Schools Conference on Wednesday, Aug. 21 at UW-Milwaukee, 2200 E. Kenwood Blvd., where guests can learn more.

Photos by Michael Timm

Writer Michael Timm, a Milwaukee Water Storyteller for the nonprofit Reflo, has done a series of environmental stories for Urban Milwaukee.

This project is funded by the Wisconsin Department of Administration, Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the terms and conditions of Wisconsin Coastal Management Program Grant Agreement No. AD239125-024.21. Funded by the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office for Coastal Management under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant # NA22NOS4190085

Fantastic!!