How Can We Reduce Salt Pollution?

Changes in state law needed, but there are also simple solutions to reduce over-salting. Final story in series

One of a dozen snowplows from across Wisconsin honks in support as it passes demonstrators with signs supporting SB 52 on March 19, 2024 outside the State Capitol. Image from video courtesy Wisconsin Salt Wise.

In Wisconsin, chloride enters our waters from water softener discharges, runoff from agricultural fertilizers like potash (potassium chloride), industrial sources—and would you guess even brine from cheesemaking?

But by far the largest contributor in the Milwaukee area is road salt. Can we reduce its use?

A report by the Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission outlines a menu of policy options to help people, businesses, and communities reduce salt use and chloride impacts. Dr. David Strifling, director of Marquette University’s Water Law and Policy Initiative, authored the SEWRPC report with law students Ivy Becker and Margaux Serrano.

Dr. David Strifling, director of Marquette University’s Water Law and Policy Initiative, authored SEWRPC Technical Report 67 with law students Margaux Serrano and Ivy Becker (not pictured) to provide a menu of policy options to reduce salt impacts. Photo by Sarah Gail Luther.

Strifling, whose background is engineering, described his role as bridging the communication gap between scientists and policymakers. “We’ve known for a long, long time that chloride has these negative impacts in the environment,” he said, “but it’s been really difficult to come up with policies to address it.”

One policy on the menu involves de-icing practices on private property, where their research identified that protection from slip-and-fall liability is a common motivation for applying too much salt.

Addressing this concern is a proposed policy modeled after New Hampshire’s novel “Green Snow Pro” certification program which took effect in 2013. In the state whose motto is “Live Free or Die,” an appropriately non-regulatory policy limits liability for de-icing contractors and private property owners certified through a training program to optimize and record salt application amounts. The intent is to remove the incentive for over-application for those wary of lawsuits should a tenant or guest slip and fall on ice.

“New Hampshire is the gold standard when we look at these kind of reform bills, and this all starts from the premise that the biggest driver of over-application of salt is fear of legal liability for slip-and-fall cases,” Strifling said.

Strifling pointed to Liberty Mutual Insurance marketing materials explaining the certification to insureds that advertises that “NH Law Changes the Game” as evidence the policy, which has also withstood legal challenges, is working in New Hampshire.

In Wisconsin, the effort to enact a bill modeled on New Hampshire produced a unique alignment between Republican state legislators and environmental advocates. Democratic legislators initially signed on, but withdrew support in January 2024 after what they characterized as unfriendly amendments.

State Senator Andre Jacque (R-DePere), who serves as chair of the Great Lakes St. Lawrence Legislative Caucus and is active with the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators, led the bill. “Anytime you’re dealing with contaminants in our lakes and streams, things that get into our actual drinkable water—I mean, we really have freshwater as just a tremendous resource,” Jacque said. “And to the extent to which that has steadily been, I guess, corrupted by chlorides, that’s a major concern.”

Senate Bill 52 would have established a voluntary certification program administered by Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP) to enroll de-icing contractors in training and reporting that would track the amount of salt spread and—barring gross negligence—protect them from slip-and-fall liability claims.

“I just think that for a lot of folks, the fear of frivolous lawsuits is what leads to pressure to over-salt, which isn’t necessarily making anybody safer or yielding any better results, but it certainly does have an impact on the environment,” Jacque said.

Senate Minority Leader Dianne Hesselbein (D-Middleton) was originally a co-sponsor of what seemed a uniquely bipartisan bill in an otherwise polarized legislature. Her communications manager explained Hesselbein’s dissent after a January 2024 amendment tweaked the language. “Ultimately, SSA2 [the January 2024 amendment] makes the legislation less about salt reduction and the environment and instead enacts more unnecessary liability shields, which she could not support,” said Chandra Munroe in an email, pointing to two minor language changes.

The amended bill, which passed the Senate narrowly in January 2024 with Republican-only support, removed the word “solely” to describe the kinds of hazards caused by snow and ice from which certified contractors would be protected from liability. It also reinforced the voluntary nature of the program by adding language that unregistered contractors cannot have that fact or evidence related to the program used against them.

The Wisconsin Association for Justice, the trial lawyers’ lobby whose lobbyists include former Democratic Senate Majority Leader Joseph Strohl, registered 180 hours opposed to the bill in 2023, according to hours the group reported to the Wisconsin Ethics Commission. It recorded another 180 hours opposed to the companion bill in the Assembly, AB 61, meaning that almost a third of all the 2023 lobbying hours the group claimed were in opposition to the slip-and-fall liability limitation legislation.

For comparison, five other groups registered just 82 cumulative hours lobbying for the bill in 2023 (and 64 hours for its Assembly companion).

Allison Madison, program manager for the advocacy group Wisconsin Salt Wise, who registered herself as a lobbyist on behalf of the Capital Area Regional Planning Commission, was chief among the proponents, which also included the Lutheran Office for Public Policy in Wisconsin, Municipal Environmental Group – Wastewater Division, Wisconsin Civil Justice Council, Inc., and Wisconsin Insurance Alliance.

In February 2024, the Assembly tabled its own bill and advanced the version the Senate approved. On Good Friday, March 29, 2024, Democratic Governor Tony Evers vetoed the bill.

In his veto message, Evers objected to “creating such a broad immunity from liability” and “creating an unfunded mandate” for DATCP. The governor’s objection also claimed that “Under this bill, an unregistered commercial applicator could falsely claim the immunity provision in this bill, and that claim could not be rebutted, due to the fact that the relevant evidence is suppressed.”

“His veto message really misrepresents this bill and the way that it is functioning in New Hampshire,” Madison said. “I’m really disappointed and frustrated that he has been so swayed by the trial lawyers.”

The veto does not change the need for action, which is widely recognized at the state, regional, and local levels.

In fact, a March 2023 letter on the initial bill from Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Stormwater Section Manager Shannon Haydin relayed that 70% of respondents to an August 2022 WDNR survey of business owners and deicing applicators identified slip-and-fall liability as “a major concern leading to the overapplication of deicers.”

Despite the setback, Madison views the fact the bill even got heard in the Legislature as a major success. She invited a dozen de-icing contractors to circle the State Capitol honking their horns in a “snow plow rally” to support SB 52 on March 19, 2024. They came.

“I see this as a huge win for our freshwaters,” Madison said. “We need to do something. But I’m just over the moon that salt was discussed on the Senate floor… People argued about this particular solution—this particular strategy for addressing it—but no one was saying that it’s not a problem.”

A former chemistry teacher, Madison appreciates that more research can better understand complex negative effects of chloride pollution, but maintains we already know enough to act now on practices that can make a big difference.

Her group Salt Wise, a coalition supported by $150,000 in grants from the Fund for Lake Michigan in 2020 and 2021, and founded from a collaboration in Madison, Wis., has taken a statewide approach to educating the public and training winter maintenance personnel.

There’s currently no training required to spread salt, and too often salt is applied as though there are no implications to its use, Madison said. Training helps “just the basic understanding that while some salt is good, more salt isn’t always better and if we’re going to use this, we need to use it as efficiently as possible and not salt first. We need to shovel first or snowblow first or plow first and then you’re just using salt if needed and as needed.”

Calibrating equipment is also important to improve the efficiency of salt application and to quantify the amounts used, Madison said.

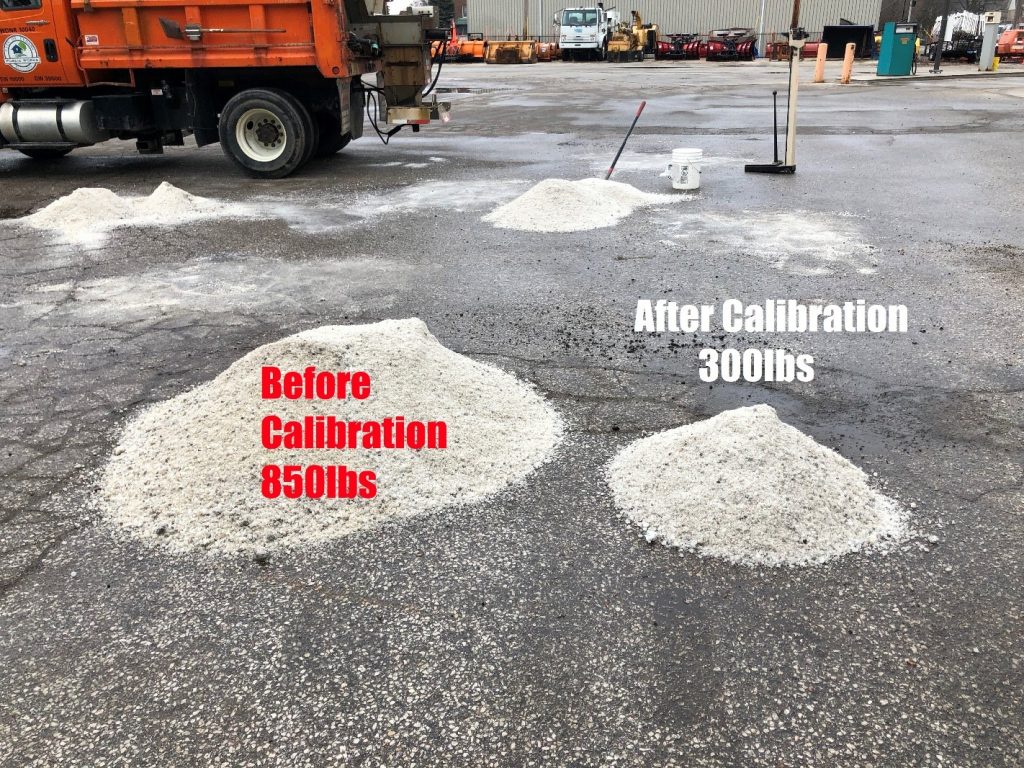

Calibrating its salt truck reduced the amount of salt this Cudahy DPW truck dispensed by over half. Before/after annotations were submitted. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Salt Wise.

“The rates that communities are using now are like 200 pounds per lane-mile, sometimes a hundred pounds per lane-mile when it’s pre-wetted with brine,” Madison said. “It used to be 500, 600—City of Milwaukee put down 800 pounds per lane-mile. Probably some operators even more than that. I think they’re trying to get people dialed down to 400 or below at this point. But the only way you really know what you’re putting down is if you have calibrated your equipment.”

And default equipment settings may be wrong. “You may think you’re putting down 400 but you’re putting down 800,” Madison said, because equipment isn’t dialed in for precision applications.

Madison pointed to the City of Cudahy, whose DPW in fall 2023 manually recalibrated a brand-new salt truck from factory settings that had been dumping out twice as much salt as the gauge indicated. Before and after photos shared are striking.

The fix cost nothing and saves tax dollars, but it required a DPW taking action to measure salt dispensed rather than trust the gauge.

These low-hanging-fruit solutions are critical now, Madison said, and untrained private contractors may not even be thinking about calibration when pouring salt into a hopper.

“They [Cudahy DPW] are working hard to be salt-wise,” Madison said. “That is where we need people to be… People are reducing their salt use by 30% to 50%—sometimes even more than that—it’s unreal. That 30-50% is sometimes just calibrating. And pre-wetting.”

The application of wet salt brine onto road surfaces reduces the salt needed to de-ice pavement and increases its effectiveness. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Salt Wise.

Municipal DPWs are starting to shift salt practices, including “pre-wetting” salt to help it stick to roads and brine spray before winter storms to help prevent ice from forming.

The City of Milwaukee is among municipalities adding salt brine to their de-icing portfolio. “All of our trucks are capable of pre-wetting the salt with brine,” said DPW’s Tiffany Shepherd in an email. “We have 25 salt trucks that also have anti-icing capabilities and five tankers for anti-icing.”

Salt Wise is also leveraging Wisconsin policy leadership to build a broader conversation and coalition around smarter de-icing among regional partners. Madison is working with the national Snow Ice Management Association (SIMA).

“Because of the work with this bill, they’re paying more attention to Wisconsin and we’re looking at putting together the first Midwest Salt Symposium, similar to the program they do in New Hampshire,” she said. “It’s likely going to be in Waukesha in September [2024] and working to bring private contractors together and talk about best practices and talk about the business side of things. But they have pitched out the idea of bringing in the state climatologists to talk about climate change and how that might be impacting their businesses.”

How could warmer, wetter Wisconsin winters influence our relationship to salt?

The endurance of black and white trapezoidal pyramids rising from Port Milwaukee salt pads could represent one bellwether to watch over the next decade, as current Port leases for salt vendors contain renewal options extending into the 2030s and beyond.

A July 2023 Martin Associates report on the economic value of Great Lakes shipping based on 2022 data among 41 ports placed salt (9.7 million metric tons) sixth in terms of cargo types moved after iron ore/bulk (39.8 million metric tons), stone/aggregate (31.7 million metric tons), grain (16.5 million metric tons), coal (11.7 million metric tons), other liquid bulk (10.2 million metric tons).

But based on available data, for Port Milwaukee, salt figures first.

And Census Bureau Customs commodities tallies for salt consistently place Milwaukee among the top 10 importers of salt nationwide.

A recent Sea Grant report detailing the reduction of Great Lakes ice cover over the past two decades carries dual implications. Reduced ice cover makes for a longer shipping season, allowing for more vessel calls. But warmer winters on land could also correspond with more efficient de-icing practices to reduce the regional demand for road salt. That could alter the economic calculus when the Board of Harbor Commissioners and Milwaukee Common Council consider future Port lease terms.

Salt constitutes roughly a third of all cargoes by weight moving through Port Milwaukee, salt storage parcels occupy about 12% percent of current Port land, and salt transport via truck means employment and intensive use of local transportation infrastructure, so the implications of shifting our relationship could be significant.

If imagining alternatives to Port Milwaukee’s salt piles seems too speculative, consider how far we’ve come in less than a century.

The SEWRPC report points out how changing policies and societal values after World War II led to our current relationship with salt. The “bare pavement” policy of road managers today emerged in the 1960s and was not always the public standard. Tire chains are now rarely used and Wisconsin restricted the use of snow tires in the 1970s.

“What we’ve seen over those decades is a shift in cultural expectations,” Marquette’s Strifling said. “People now expect to be able to drive 65 miles an hour on the freeway an hour after a blizzard or in some cases even during a blizzard. And it’s just not realistic, if we’re going to do anything about this problem. You got to slow down, got to accept some inconvenience in some of these cases. And people just don’t have that awareness, I don’t think. And that’s part of what makes Salt Wise and programs like that so important. Again, my driveway was a sheet of ice this [January 2024] morning and I’m certainly not suggesting that we should stop salting roads. I don’t want to drive on icy roads any more than the next person does. But there’s a limit… When you’re walking around and you’re crunching [salt] under your boots, that’s too much.”

Photo Gallery by Wisconsin Salt Wise

This is the third story in a series by Michael Timm, a Milwaukee Water Storyteller for the nonprofit Reflo, who did our earlier series on reintroducing the sturgeon into the Milwaukee River. He holds a 2013 master’s degree in freshwater science from UW-Milwaukee. He previously wrote and edited for the Bay View Compass newspaper.

This project is funded by the Wisconsin Department of Administration, Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the terms and conditions of Wisconsin Coastal Management Program Grant Agreement No. AD239125-024.21. Funded by the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office for Coastal Management under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant # NA22NOS4190085

For those curious to learn more, a link to the SEWRPC chloride impact reports, including TR 67, can be found here: https://www.sewrpc.org/SEWRPC/Environment/ChlorideImpactStudy.htm

I agree with much of what this article has to say. I dont envision salt use going away anytime soon but in the short term we can at least calibrate the equipment better. More efficient use and training should be a priority but liability shields will have to be put in place to protect both contractors and businesses from lawsuits. Sad to see that it looks like Evers sold us out to the trial lawyers again, what a hypocrite.