Where Plankinton and Wells Meet

Two streets, two Milwaukee pioneers and a downtown square with a curious history.

Most of the people who came to Milwaukee in its early years of settlement were young. Daniel Wells, a Maine native, came to Milwaukee in 1835 when he was 27. He died here at the age of 93 after gaining wealth in a variety of endeavors almost too many to mention. He was an investor in banks, railroads, insurance, hotels, lumber, wool, and grain, and in other projects, including real estate. The Wells Building at 324 E. Wisconsin Ave. carries his name.

John Plankinton was only 24 when he arrived in the city in 1844. The wealth he accumulated during his lifetime was derived primarily from the meatpacking industry, but he too was involved in railroads, hotels, and real estate. He died in 1891 at age 71. The Plankinton Building at 161 W. Wisconsin Ave. is named for him.

Both street names are invariably invoked when describing the location of the triangle created by the intersections of N. Plankinton Avenue, W. Wells, and N. Second streets. A nineteenth century building occupied that triangle until 1919, when it was demolished. (A photo of the building can be seen here.) The City Land Commission urged the Common Council to buy the land as “a breathing spot” for passengers of the streetcars that traveled on the three streets adjacent to the triangle.

By “a breathing spot” the commission meant public restroom facilities for those who were transferring streetcars at that busy intersection. But the War Mothers had a different idea. They wanted a memorial for their sons who gave their lives as soldiers and sailors in the just-ended World War I. They called it the World War Memorial without giving it a number, unaware that there would be another World War two decades later.

Fifteen years later, in 1934, despite opposition by the Milwaukee Art Commission and some aldermen, the memorial was unveiled by two Gold Star Mothers, Mrs. Carl Wallber and Mrs. Bernhard Germershausen. The American Legion Band provided music with numerous patriotic groups in attendance at the ceremony. The memorial was a flagpole atop a base commemorating those who lost their lives serving in the conflict. The Park Board added water bubblers and benches to the triangle.

Two decades later the memorial was in bad shape. The top and the base were tarnished and the paint on the pole was peeling. One concerned citizen recommended sprucing up the memorial in the unnamed triangle that was described by its location at N. Plankinton Avenue and W. Wells Street.

The World War Monument was still there in 1968 when after business hours 14 men went into the Selective Service offices in the Germania Building (then known as the Brumder Building) across W. Wells Street from the triangle. They were Vietnam War protestors who would become known as the “Milwaukee 14.” The group carried about 10,000 draft records in burlap bags from the offices and placed them at the base of the flagpole monument, where they set them on fire. The anti-war protestors then sang and prayed while watching the fire and waiting to be arrested. (Photos of the event and the base of the World War Monument can be seen here).

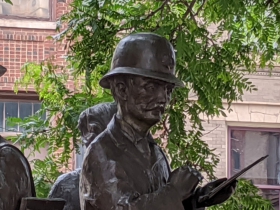

The triangle underwent a major overhaul in 1989. The World War Memorial was replaced with the Letter Carriers’ Monument that is there today. The nation’s letter carriers unionized in Milwaukee in 1889 in a building across N. Plankinton Avenue from the triangle. For the centennial celebration of the event, 4,000 letter carriers and their families descended on the city from all over the country. The four-day festivities included a parade, banquets and the unveiling of the new monument.

The six-foot statue on a four-foot base shows three letter carriers. One is depicted in the uniform prevalent at the time of unionization in 1889. Another, a Black man, is dressed in the garb from fifty years later in 1939. The third, a woman, is shown in the attire worn a century later in 1989. The sculptor was Elliot Offner.

In the last few years, both NEWaukee and the Milwaukee Downtown Business Improvement District, BID #21, have drawn attention to the shaded triangle. Public art, music, food, and games have made their appearance. Surveys of the opinions of the public were collected. Now their ideas have been incorporated in the space thanks to the BID. A century after “a breathing spot” at the triangle was initially proposed there will be one, but it will be for dogs, not humans; dog-friendly grass has been installed. Also, a low wall for people to sit on has been erected, a stone walkway has been laid, and plants have been put in. The enhancements are still in progress.

Maybe the most efficient name would include its location, something like the Plankinton and Wells Park or the Plankinton-Wells Square. No matter what it is called, the little triangle has played a notable role in Milwaukee’s history.

Photo Gallery

Carl Baehr is the author of Milwaukee Streets: The Stories Behind Their Names and From the Emerald Isle to the Cream City: A History of the Irish in Milwaukee.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

City Streets

-

The Curious History of Cathedral Square

Sep 7th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

Sep 7th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

-

Gordon Place is Rich with Milwaukee History

May 25th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

May 25th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

-

11 Short Streets With Curious Names

Nov 17th, 2020 by Carl Baehr

Nov 17th, 2020 by Carl Baehr