I Served As a Pandemic Poll Worker

We would all be paid! I felt the economy rebounding under my feet.

This past March, amid the growing pandemic, I came to a decision that in-person voting was absurd. Mail-in voting is the norm in liberal states like Washington and Oregon as well as the deep red state of Utah, with no problems reported. Why conduct an election in the 21st century the way Caesar Augustus ran a census two millennia earlier? I had just filled out my U.S. Census form from home. Why not do the same to vote?

On March 26th, I had already cast my ballot by mail, and was on the list to do so for all upcoming elections in 2020. But that day, Milwaukee County Clerk George L. Christenson and other officials urged voters to claim they were “indefinitely confined” to their residence due to COVID-19, and to request that absentee ballots be sent to them for all upcoming elections — no photo ID required.

The idea that my enforced isolation could provide a loophole to allow me to vote remotely until the end of my life without making an annual application to do so appealed to me. I never wanted to vote in person again. I wondered how such a request would play in Ozaukee County, where I am indefinitely confined.

I wrote to Carolyn Fochs, the clerk of the City of Mequon, to request the change, which she readily granted. Looking for a story angle, I asked her “does the city have enough workers for the polls on election day?” The shortage of poll workers statewide was much in the news at the time.

“At this time, I believe so,” Fochs wrote, adding, “Are you willing to work if we need you?”

I wasn’t expecting that.

Out of an abundance of civic duty, I answered, “yes,” figuring the call would never come.

A Call to Duty

The next day the call came.

My assistance would be required at Range Line School on election day. “We’ll see about that,” I thought to myself. “No way this election will take place at the polls.”

The afternoon before the election, I heard from Al Turner, the chief election official for Mequon Wards 19, 20 and 21. He told me to be at my post at 6:30 a.m. on Tuesday, if the election were to be held. For now it was off, which suited him and the other election workers just fine, he said. “Good. Let’s hope it stays that way.” I said. Just thirteen hours before the polls were to open, however, the election was back on, and I was to have a front row seat as an official functionary of what the New York Times would call “an electoral system stretched to the breaking point … a dangerous spectacle that forced voters to choose between participating in an important election and protecting their health.”

It was not just the voters who risked their health, but the poll workers as well. At 66 years of age, I am an automatic member of the high-risk population for this disease. But I had passed a health checkup just weeks before, and I had no symptoms. Frankly, I was eager to get out of the house. I had not been through the doors of Range Line School since June 1967, when I walked out with my 8th grade diploma. Yet here I was, a potential martyr on the front lines of democracy. Public health officials tell us we should know in a few days if the in-person election led to a spike in infections. During these bleak days, I have something to look forward to.

More Polling Places than the City of Milwaukee

The City of Mequon had 8 discrete polling places in seven locations to serve its 17,550 registered voters on election day. The City of Milwaukee, with 296,589 registered voters, had only five “Voting Centers” in operation, down from the typical 180. This disparity further heightened the absurdity of the situation.

Election Day Dawns

It was still dark when election day dawned for me. I bicycled past a deserted country club to my old grade school, now known as the Range Line Recreational Center. The polling place for District 8 (Wards 19-21) was in its Conference Room, which was added to the building decades after I had graduated. Any sentimental attraction to the location went right out the window, from which I could see the skeletons of dead trees killed during the recent Emerald Ash Borer pandemic. The dense stands were upwards of 30 years old, sown from wind borne seeds decades after I graduated from 8th grade. I pondered mass extinctions, and if I was to become part of one. Now, off to work!

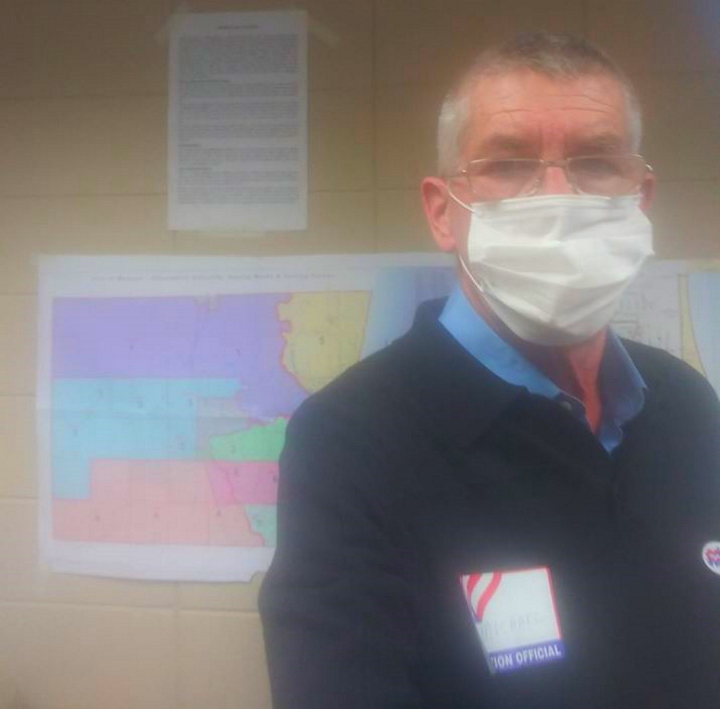

Following the oathing, I affixed a sticker to my sweater to inform all and sundry that “Michael” was an Election Official. This was not the only wardrobe enhancement provided at taxpayer expense. I was also outfitted with blue surgical gloves and instructions to wear them and an accompanying face mask at all times. I was then told that I would be performing a variety of tasks over the course of a 15-hour shift. I was first assigned to the registration table, where first-time voters could sign up to exercise their franchise. The tabletop was filled with instructions, and examples of approved forms of identification. There was also a list of local felons ineligible to vote that must be checked against for new registrants. Among those listed, I noted, was a woman born in 1925. She never showed up, nor did anybody else while I sat there for a half hour or so.

At the entrance was a table for the “greeter,” who was to welcome voters, to check if they were in the right place, and to instruct them to apply hand sanitizer before they approached the next table, at which they were to be provided with a numbered slip bearing their name. Masking tape strips, six feet apart, were applied to the carpeted floor. There were three of them, and that’s all that were to be needed that day for crowd separation, it was to turn out. Beyond the registration table a husband and wife sat with the poll books. It was their job to check the prospective voter’s registration and identification before the voter signed the book. There was another table for being issued the ballot, and beyond that lie the voting booths. Finally, the ballots were to be fed into the counting machine, located at the end of the circuit. Ordinarily, they would be tallied by evening’s end, but a ruling by two supreme courts (state and federal) delayed the release of the results until Monday, April 13th, adding an anticlimax to the multiple dramas proceeding this election day.

The Absentee Ballots Arrive

When the doors opened for voting at 7 a.m., there was a brief flurry of no more than a half-dozen or so early birds. Shortly thereafter, a pair of burly men wearing Mequon Auxiliary Police uniforms deposited a number of sealed boxes containing some 700 absentee ballots, arranged alphabetically, and numbered accordingly. These far outnumbered the 419 total ballots cast in the previous election by the 2,107 registered voters of Wards 19-21, City of Mequon. More were to come in the afternoon’s mail, numbering in the aggregate over 1,000 of the 1,199 ultimately to be cast. All of the absentee ballots were to be fed into the Dominion Voting Systems machine over the course of the day in batches of 10. This job, like many others at the polling place, was to rotate among staffers during the course of the day. One would read the name of the voter aloud, while another would feed the ballot into the machine, all under the watchful eye of a veteran worker. This was to take place throughout the day, interrupted only by actual voters, who fed their ballots into the machines themselves, and who were given precedence. The ballots could be inserted up or down, front or back, which introduced a bit of variety into the mundane activity. An electronic screen would record the number of votes cast, and issue a “beep” when it was ready to digest another. Occasionally a ballot would be rejected for a technicality. Usually it was a case of a voter signifying a presidential party preference, yet failing to also cast a vote for a specific candidate for that office, while the remainder of the ballot was filled out. The inspector pushed a button overriding the machine’s objection, and the vote count went on, as did the day.

Transferred to “Greeter” Role

After a number of hours alternating duties of slicing open envelopes and passing them to another to remove the ballots, and then feeding them one at a time in batches of ten into the machine whilst reading the names aloud, I was given the role of “Greeter.” Although Mequon had eight polling places, two of them were in this building; all the rest were single-district locations. Wards 13-15 voted in the gymnasium of the old school. When electors arrived, I was to ask their street address, which I would check against a file to see if they were in the right place. If they were from Wards 13-15, as was occasionally the case, I was to direct them to the gym. Ordinarily this would involve simply sending them down the hall, but that was closed off, so they had to head outside to a different entrance. I have a good head for addresses, and a fine sense of Mequon geography, so this was fun for me.

There was a slight surge of activity around the noon hour, and there was to be another after 5 p.m. Perhaps these were at-home workers who plot their day according to regular business hours. A few were likely “essential workers,” such as a City of Milwaukee policeman who came to cast his ballot, and a few others bearing uniforms of the mechanical trades. One early-morning masked-and-gloved couple wore black armbands. The husband also wore a sign expressing dismay that the in-person election had not been postponed for the sake of public health. His wife was garbed in a surgical gown, much as was Robin Vos as he worked a drive-thru voting operation in Rochester. The difference was that she was an actual M.D., as you could tell from her name, embroidered on her gown. Throughout the day a dozen or so people brought in ballots they had received in the mail, and were going to mail in by April 13th. But the rules famously changed overnight to April 8th, and they took the time to deliver their absentee ballots to the polling place. I wondered how many others did not. Many voters took the time to thank the election workers for their efforts, which was touching and deeply appreciated. I heard no complaints of absentee ballots requested, yet not received, as had bedeviled voters in Milwaukee and elsewhere in the state.

I thought it would be nice to issue “I Voted” stickers to the voters, but due to social distancing policies, I was informed that this was not to be done. A roll of the stickers remained at the foot of the voting machine, undisturbed and undistributed. This election was sucking all of the fun out of voting. Why, in the past that sticker would be worth a free election day drink in any number of taverns around town. It has been a long time since taverns were closed on election day.

A Few Glitches

Toward ballot #500 or so, the Dominion voting machine started getting balky, rejecting perfectly good ballots, and being particularly fussy about accepting them in any event. We would feed them in again, upside down, or backwards until they took. I developed a technique that involved crossing my fingers, usually to little avail. Things were slowing down, yet the machine eventually accepted the ballots. The machine’s optics were being strained by the inevitable lint and dust introduced into the workings by the intense activity. A special sheet was inserted to clean the lenses, and the machine was then more accepting of the ballots it was fed.

Around 5 p.m., Mequon Mayor John Wirth showed up, bearing a half-dozen boxes of pizza from Zarletti‘s, open for delivery. Around that time I got a message from my neighbor Oliver Hunt, the owner of the Hidden Kitchen in Milwaukee, asking me how things were going. I told him I was concerned that I wouldn’t get out of the place before the beer store closed at 9 p.m. I did not realize when I signed up that my official position did not end when the polls closed at 8 p.m., but was to extend into a period of mandatory overtime.

Missing Ballots!

At 8 p.m. promptly the polls were closed, there being no potential voters in line, unlike in Milwaukee, where voting was to continue for hours in some locations. The Chief announced the conclusion by crying, “Hear Ye! Hear Ye! Hear Ye! The Polls are now Closed!” An oath-taking and a “Hear Ye!” all in the same day.

I was prepared to immediately bolt for the door, but was informed that my services were still required for the physical count of the ballots. The machine was opened, revealing over a thousand paper ballots in its hold, scattered in all directions as they had fallen. These were to be sorted in piles of 25, and then passed on to another to be recounted, and then tabulated. This was done, the count was announced, and we were informed that we were two ballots short. The piles were recounted, and then recounted again, with the same results: Two ballots short. One election official, an ATM technician by trade, suggested the voting machine be reopened to check for the missing ballots. This was done, but no ballots were evident. Would we ever get out of here? Then the official got down on the floor, reached his arms into the workings of the machine, and pulled out the two missing ballots.

I was given the instruction to open the door to admit a visitor calling on official business, I did so, and kept on going, as urged by a fellow worker, who thanked me for my help. My day was done. My night was just begun when I returned home to find some Lakefront beers awaiting my return, thanks to my neighbor.

“This is what the complete collapse of a state’s political system looks like,” said Politico about this election. I am proud to say I played a role in the disaster.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

More about the Coronavirus Pandemic

- Governors Tony Evers, JB Pritzker, Tim Walz, and Gretchen Whitmer Issue a Joint Statement Concerning Reports that Donald Trump Gave Russian Dictator Putin American COVID-19 Supplies - Gov. Tony Evers - Oct 11th, 2024

- MHD Release: Milwaukee Health Department Launches COVID-19 Wastewater Testing Dashboard - City of Milwaukee Health Department - Jan 23rd, 2024

- Milwaukee County Announces New Policies Related to COVID-19 Pandemic - County Executive David Crowley - May 9th, 2023

- DHS Details End of Emergency COVID-19 Response - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Apr 26th, 2023

- Milwaukee Health Department Announces Upcoming Changes to COVID-19 Services - City of Milwaukee Health Department - Mar 17th, 2023

- Fitzgerald Applauds Passage of COVID-19 Origin Act - U.S. Rep. Scott Fitzgerald - Mar 10th, 2023

- DHS Expands Free COVID-19 Testing Program - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Feb 10th, 2023

- MKE County: COVID-19 Hospitalizations Rising - Graham Kilmer - Jan 16th, 2023

- Not Enough Getting Bivalent Booster Shots, State Health Officials Warn - Gaby Vinick - Dec 26th, 2022

- Nearly All Wisconsinites Age 6 Months and Older Now Eligible for Updated COVID-19 Vaccine - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Dec 15th, 2022

Read more about Coronavirus Pandemic here

Plenty of Horne

-

Villa Terrace Will Host 100 Events For 100th Anniversary, Charts Vision For Future

Apr 6th, 2024 by Michael Horne

Apr 6th, 2024 by Michael Horne

-

Notables Attend City Birthday Party

Jan 27th, 2024 by Michael Horne

Jan 27th, 2024 by Michael Horne

-

Will There Be a City Attorney Race?

Nov 21st, 2023 by Michael Horne

Nov 21st, 2023 by Michael Horne

This is why we support UrbanMilwaukee! Reporters willing to risk missing out the closing of the beer store to serve their country in a democratic election during a pandemic.

Kudos to you Michael, and all those who voted, especially the brave souls who voted in person.

Great article Michael, keep on biking and oh by the way, thank you for your service to the citizens of Wisconsin.