Can More Cities Become Tech Innovators?

Study suggests federal government invest in cities like Madison. Good idea?

A recent paper from the Brookings Institution and the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) worries that in recent years technology innovation has concentrated in a very small number of metropolitan areas. Entitled The Case for Growth Centers: How to Spread Tech Innovation Across America, the paper argues that the gap between regions has reached extreme levels in the U.S. innovation sector.

It reports that five metro areas—Boston, San Francisco, San Jose, Seattle, and San Diego—accounted for more than 90 percent of the nation’s innovation-sector growth during 2005 to 2017. While accounting for just 3 percent of the nation’s jobs, innovation industries generate 6 percent of the nation’s GDP, a quarter of its exports, and two-thirds of business R&D expenditures.

(ITIF, the co-author of the study, is less known than Brookings. It concentrates on issues relating to technology, entrepreneurship, and innovation. In recent years, one of Brookings initiatives is analyzing issues related to place: why do some places enjoy economic success while other are left behind.)

The report argues that the regional imbalance is not self-correcting: in the previous industrial economy, firms competed on cost; as costs rose with growth, they would look for lower cost areas. Instead of competing on costs, the innovation industries of the last 40 years largely compete on the richness of the local innovation ecosystem.

This growing divergence, the report argues, is bad for the many regions that have been left behind. “Many Americans reside far from the opportunities associated with the nation’s innovation centers, undercutting economic inclusion and raising social justice issues.”

It is bad for the “super star” cities, leading to a higher cost of living, particularly due to escalating housing costs and congestion.

It is also bad for the nation, as “the costs of excessive tech concentration have meant less overall innovation industry activity in the United States in part as companies increasingly move activity from high-cost U.S. tech hubs to medium-cost foreign hubs.”

The report argues that markets “alone won’t solve the problem; federally led, place-based interventions will be essential in ameliorating it.” Arguing that high tech firms are attracted to places with many other high tech firms so it is very hard for cities to break in, the report advocates a federal initiative to establish growth centers in the middle of the country.

In arguing for concentrating on a few places, the report points to Amazon’s recent decision on where to locate its second headquarters. It received 238 proposals, many hoping that winning Amazon’s favor would be transformative. Amazon narrowed the proposals to 20. Except for Columbus, Ohio, Indianapolis, Nashville, and Pittsburgh, “the 20 finalists were either existing self-sustaining hubs (e.g., Austin, Texas, Boston) or extremely large metro areas (e.g., Los Angeles and New York).” Amazon chose New York and Washington.

In other words, Amazon made the safe decision, selecting locations that least needed the proposed second headquarters. In the end, Amazon further reinforced the trend towards concentration.

The Brookings-ITIF report proposes that the nation act to counter regional divergence by creating eight to ten “growth centers.” This transformation would be fueled by a research and development funding surge. The authors estimate that the program would cost the federal government on the order of $100 billion over 10 years, which “is substantially less than the 10-year cost of U.S. fossil fuel subsidies.”

They then turn to the question of which metros might be chosen. They narrow down the list by eliminating metro areas with fewer than 500,000 residents. They also eliminate New York and Los Angeles– the country’s “two mega-regions”—along with Washington, D.C., described “as de facto superstars and factors in the nation’s imbalanced innovation map.” Other cities such as Raleigh, N.C., Boston, San Francisco, Seattle, Austin are “set aside because they are already self-sustaining superstars.”

Finally, they eliminated otherwise viable metro areas that lie within 100 miles of the center of an existing innovation center “because their further emergence won’t significantly improve the nation’s current entrenched spatial alignment. … For this reason, formidable and deserving metro areas such as Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Worcester, Mass. fall off the list.”

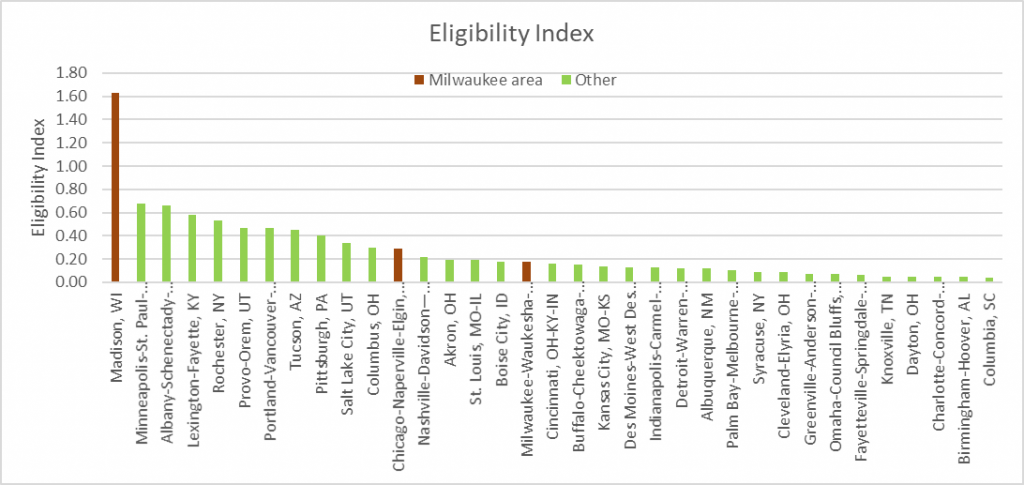

For the remaining metros, their regional innovation capacity is assessed using “an eligibility index” based on a weighted average of four numbers: the rate of STEM R&D spending by local universities, patent filings, the share of adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher, and the rate of STEM doctoral degrees granted by universities in the metro area.

The following graph shows the 35 metros with scores greater than zero, “reflecting above average strengths in innovation and workforce development, and thus potential for growth center status.”

Three local metros are on this list: Madison (ranked first) Chicago (12th) and Milwaukee (17th). In fact, a Journal Sentinel article was headlined, “’We need 10 more Madisons’ to foster tech growth in the heartland, Brookings and ITIF report says.”

The report describes these metros as “potentially transformative growth centers dispersed across the nation … in 19 states (and) in multiple regions, especially in the Great Lakes, Upper South, and Intermountain West, and they exist often at far remove from the coastal superstars. Rather than being concentrated, they are quite widely distributed, suggesting the nation contains much more untapped potential in the innovation economy, in many more places, than is often presumed. … Numerous metropolitan areas in most regions have the potential to become one of America’s next dynamic innovation centers.”

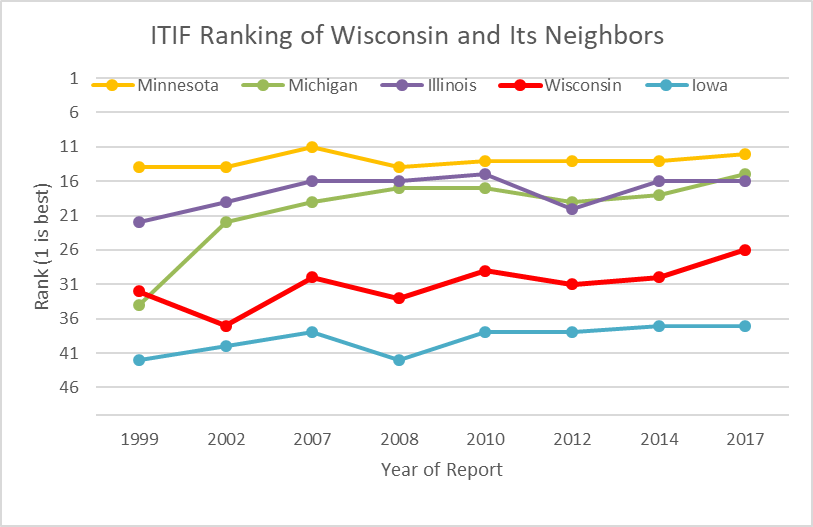

Inadvertently perhaps, the difficulty of transforming to the New Economy is reflected in the State New Economy Index, also published by the ITIF. The index uses 25 indicators in five different categories: Knowledge Jobs, Globalization, Economic Dynamism, The Digital economy, and Innovation Capacity. The chart below shows the rankings over the years for Wisconsin and its neighbors.

The indicators are based on data and include employment of IT professionals outside the IT industry, the educational attainment of the workforce, immigration of knowledge workers, the export orientation of manufacturing and services, business churn (start-ups and failures), IPOs, information technology in health care and state government, the number of scientists and engineers in the workforce, patents, and movement toward a clean energy economy.

The relative stability of the states’ rankings reflects the fact that it is very challenging for a state to improve its position. Since 1999, Mississippi, followed by West Virginia, has ranked at the bottom and Massachusetts at the top. Attempting to change these presents something of a chicken and egg problem.

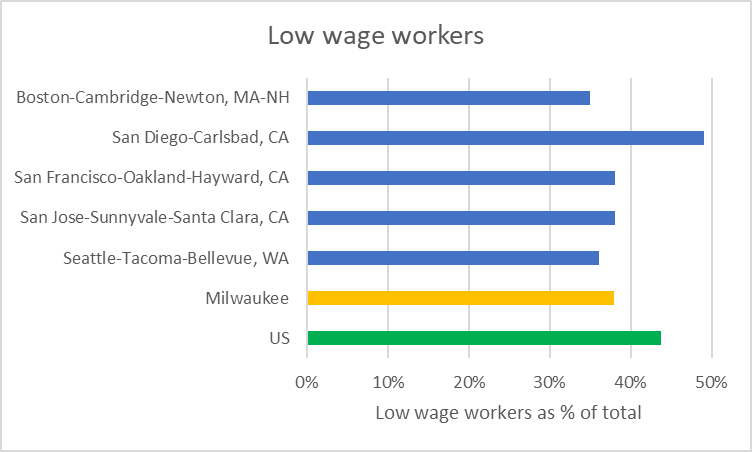

It is worth noting that moving towards the new economy is not a panacea for other problems. Consider the problem, addressed in last week’s Data Wonk column: that of low-wage workers who work full time but are still economically stressed. The next chart plots the percentage of low-wage workers in the five top technology growth metros (San Francisco, Seattle, San Jose, Boston, and San Diego), as well as Milwaukee and the nation. The percent of low-wage workers is not much higher in Milwaukee than for high-tech hot-beds like San Francisco or Seattle.

The report from Brookings and ITIF suggests that “rather than on saving the most distressed cities and towns across the vast totality of America’s economy,” we concentrate on an intense effort to expand the new economy to eight or ten metros with the greatest potential. This recommendation, however, presents a potential political challenge. Compared to the most distressed cities and towns in American, the 35 metro areas the report singles out for help are doing relatively well. Perhaps a national strategy to help both groups of cites and towns — the distressed and those with innovative potential — is needed.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson