Marcus Center at a Crossroads

Are upgrades to the Marcus Center and changes to the Kiley grove necessary?

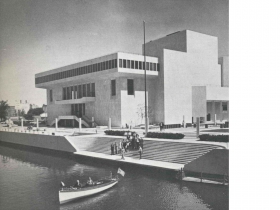

The Marcus Center for the Performing Arts in 1969. Image provided to Historic Preservation Commission by Jim Shields.

The Marcus Center for the Performing Arts has had a whirlwind 12 months. In June one of its anchor tenants, the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, broke ground on its own music hall, formalizing a plan to vacate the center. Partially in response, the organization unveiled a redevelopment plan for the campus in December focused on long-term sustainability. Included in those plans are a new west lobby, a large donor lounge, reconfigured seating arrangement in Uihlein Hall, translucent glass for the east facade and a reconfiguration of the grounds.

But those plans were put on hold in February, when a temporary historic designation for the campus was approved. Landscape architect Jennifer Current and architect Mark Debrauske submitted the nomination, and Current’s testimony at the February hearing centered around the grove of 36 horse chestnut trees on the building’s south side. A hearing on permanent designation is scheduled for April 1st.

The 3.65-acre complex at 929 N. Water St. originally opened in 1969. Designed by architect Harry Weese, the grounds include a landscaping plan from famed landscape architect Dan Kiley.

But the Marcus Center, contends it’s a matter of when, not if, the grove must go. “Everyone here is convinced the trees are at the end of their life,” says project architect Jim Shields of HGA during an interview with the Marcus Center management team and architect. A Marcus Center-commissioned report from Hoppe Tree Service notes that four of the trees are likely to “fail” (or fall over) in the coming year. According to the Marcus Center, another five trees are also near the end of their lives.

“These are living trees, they’re not going to last forever,” says Marcus Center vice president of sales and marketing Heidi Lofy. “These groves don’t last forever. I think there is some sense in the community that this one would,” says Shields. Lofy contends that the grove would eventually fail from the moment it was planted. “How they crack and how they come apart is just the kind of tree they are,” says Lofy.

The Marcus Center says new, mature trees can’t be added because of how close the trees are to one another. The root structures of the existing trees have become intertwined, and new trees would struggle to get light. Unlike parks like Frederick Law Olmsted‘s Lake Park where trees can be replaced over time, Shields notes that the loss of a single tree in a Kiley work can quickly cause the whole thing to fail.

The non-profit, led by president Paul Mathews, envisions removing the grove and replacing it with 18 mature honey locust trees and a central lawn. The new trees, which have smaller leaves and would allow more light through, would be placed in the footprints of the two outer rows of the existing grove according to Shields. The architect even has the specific trees picked out at Johnson’s Nursery in Menomonee Falls.

Lofy says the Marcus Center would reclaim the chestnut wood for use either within the center or elsewhere in the community.

The Marcus Center has other issues with the grove beyond the health of the trees. Mathews notes that the grove, which sits below grade, doesn’t comply with the American with Disabilities Act. “We can’t treat people in wheelchairs as second class citizens,” says Mathews. Shields stresses that the choice of gravel is a further impediment to accessibility.

The new grounds, which Mathews takes care to point out aren’t a revenue generator for the center, would allow the entire space to be used in a unified fashion. The sound booth at the rear of the Peck Pavilion would be relocated, allowing the new lawn to have a direct sightline to the outdoor stage. New fountains would replace the existing one along N. Water St., and are envisioned to allow visitors to touch them. An outdoor cafe is planned at the building’s southwest corner along the river and near the pavilion.

Mathews says that more than 100 events, all free, are held on the grounds every year. Shields believes adding new lights and movable furniture, a principle endorsed by urban theorist William H. Whyte, will encourage more usage of the grounds even when there is no event.

But reconfiguring the grounds isn’t the only thing the Marcus Center has planned.

Mathews sees the whole plan as the logical next step. “This place has been evolving since the day it opened,” he says. The redevelopment plan is designed to improve the center’s connection to the community, both by programming and physical appearance. “From the outside the building can be very foreboding,” says Mathews.

A main entrance along N. Water St., covered in what Shields refers to as “limousine glass,” is part of this problem. Shields said regardless of the time of day, it’s tough to see what’s going on inside. The redevelopment plan includes swapping it for a translucent glass. “They didn’t have this 25 years ago,” said Shields.

That same new glass will be used on the south side where the new donor’s lounge will protrude from the building. The lounge, similar to private clubs found in new arenas, is designed to grow the center’s revenue. The columns, central to Weese’s original design of the building, will be maintained within the lounge. The columns on other sides of the building have been largely erased by multiple alterations.

The non-profit has a 99-year lease with Milwaukee County to operate and maintain the facility, and Mathews says it’s the only county-owned building that doesn’t have any deferred maintenance. He notes this allows the plan to focus on improving the capabilities of the building, instead of simply trying to keep it functional.

One of those enhancements is reconfiguring the seating in Uihlein Hall. The theater currently seats 2,305, but approximately 110 seats will be lost as additional aisles are added. The new aisles will improve the accessibility of the otherwise long seating rows as well as providing more seating for those with wheelchairs and other mobility devices. The rigging around the stage will also be improved, with the permanent orchestra shell removed, allowing for traveling shows to use more of the stage.

The building’s west facade, which serves as the entrance to the Wilson Theater, will be revamped. An exterior staircase will be wrapped with a new curved, glass lobby, intended to create a more welcoming experience for theatergoers. The roof of the lobby will serve as an ADA-accessible outdoor deck with river views for the Bradley Pavilion, replacing a small deck there today. Along the river a floating dock and ramp are planned, designed to provide accessibility, including to the ever-changing river, compared to the current concrete stairs.

An outdoor space in the middle of the building, the Fitch Memorial Garden, will be covered. The change is designed to create a space that can be more reliably rented out.

Digital signage will replace the banners that can be found both inside and outside the building. Mathews says it’s a change that will save staff time (and money) and allow the organization to feature more of its tenants. A massive projection system is planned for a portion of the building’s south facade, better showcasing productions by the Florentine Opera, Black Arts MKE, First Stage, Milwaukee Ballet and Milwaukee Youth Symphony Orchestra or Broadway shows that happen inside.

“Whether the symphony is leaving or not, these are changes we would make,” says Mathews. “None of the non-profits pay what it actually costs to rent the space,” says Lofy. The changes will allow the center to grow its earned revenue, which currently accounts for 85 percent of its operating budget, while financial support from Milwaukee County declines.

Looming Preservation Battle

The timing and nature of the plans is all subject to the complex’s potential designation as a historic building. It’s been granted temporary historic designation, effectively a 180-day injunction. A hearing on its permanent designation is scheduled for April 1st.

If the Historic Preservation Commission approves a permanent designation, the center could appeal the decision to the Common Council. The council, unlike the commission, is able to consider economic factors in its argument. Mathews told Urban Milwaukee that should the campus be permanently designated, his organization would appeal the decision to the council.

Asked if the original renderings, in which the 18 new trees are hard to see, played a role in the public outrage over the elimination of the trees, Shields said, “I’m sure that’s part of it.” A new rendering depecits the mature trees Shields has selected.

Shields also believes that former Milwaukee Journal Sentinel art and architecture critic Mary Louise Schumacher left out a detail to strengthen an argument for saving the Kiley landscaping. “I think she intentionally didn’t tell her readers that there were to be 18 trees planted,” says Shields. Her December piece doesn’t mention the replacement trees, but a later January piece notes that 18 trees are planned. Schumacher announced in late January her position was a casualty of Gannett’s continued downsizing.

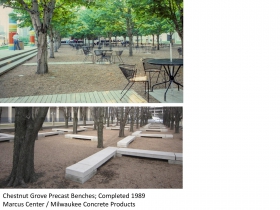

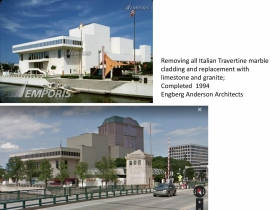

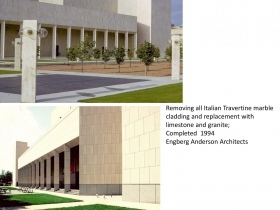

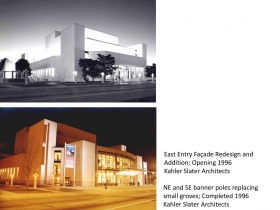

The architect, who previously served on the Historic Preservation Commission, will make his case that the building isn’t historic because its integrity has been compromised. Buildings can be designated historic for 10 reasons according to the city’s ordinance, but first they must pass an integrity threshold: “‘Historic, architectural and cultural significance’ means the attributes of a district, site or structure that possess integrity of location, design, settings, materials, workmanship and association which consider the following.” Shields, as he did during the hearing on the temporary designation, will cite the numerous alterations made to the building, including recladding it in limestone, replacing the front lobby and repeatedly altering the grounds.

But before Shields gets to make the case that the building isn’t historic in its current state, the Marcus Center staff will come before the commission to secure approval to remove four of the trees. The hearing will be held at 3 p.m. on March 4th.

Until the situation is resolved, the grove is surrounded by an ominous fence. The fence has been up since February 21st. Mathews says it came as a result of the final arborist report received February 13th and a discussion with the firm’s insurance agent. Lofy says the group hopes to avoid what happened in New York City’s much busier Bryant Park where a falling tree limb injured five people.

Whatever happens, the Marcus Center project is bound to test the limits of the city’s historic preservation ordinance. As Shields himself notes, this is a truly unique case.

Renderings

Shields’ Presentation on Building’s Compromised Integrity

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits, all detailed here.

More about the Marcus Center redevelopment

- Eyes on Milwaukee: Marcus Center Unveils New Grounds - Jeramey Jannene - Nov 14th, 2022

- Eyes on Milwaukee: Marcus Center Starts Construction On Former Chestnut Grove - Jeramey Jannene - May 31st, 2022

- Plats and Parcels: Marcus Center Begins Redevelopment - Jeramey Jannene - Sep 20th, 2020

- Eyes on Milwaukee: Council Says Marcus Center Not Historic - Jeramey Jannene - May 7th, 2019

- Eyes on Milwaukee: Committee Says Marcus Center Isn’t Historic - Jeramey Jannene - Apr 30th, 2019

- Marcus Center Trees Removed Before Permit Issued - Jeramey Jannene - Apr 9th, 2019

- Eyes on Milwaukee: Marcus Center, Kiley Grove Deemed Historic - Jeramey Jannene - Apr 1st, 2019

- Murphy’s Law: Kiley’s Chestnut Grove Provokes Hot Debate - Bruce Murphy - Mar 7th, 2019

- Eyes on Milwaukee: Marcus Center Decision Delayed A Month - Jeramey Jannene - Mar 5th, 2019

- Eyes on Milwaukee: Marcus Center at a Crossroads - Jeramey Jannene - Mar 4th, 2019

Read more about Marcus Center redevelopment here

Eyes on Milwaukee

-

Church, Cupid Partner On Affordable Housing

Dec 4th, 2023 by Jeramey Jannene

Dec 4th, 2023 by Jeramey Jannene

-

Downtown Building Sells For Nearly Twice Its Assessed Value

Nov 12th, 2023 by Jeramey Jannene

Nov 12th, 2023 by Jeramey Jannene

-

Immigration Office Moving To 310W Building

Oct 25th, 2023 by Jeramey Jannene

Oct 25th, 2023 by Jeramey Jannene

” honey locust trees “. Unfortunately, we live on a street that was planted with these despicable trees when the elms that succumbed to disease had to be replaced.

Instead of large, easy to manage leaves, honey locusts have millions of minuscule leaves and irritating stems that infiltrate every crack, space and opening that exists. When wet, they attach to shoes as if they are mating and as a result are distributed inside homes and vehicles with infuriating success.

Just say “no” to honey locusts.

Marcus has no deferred maintenance partly due to the continued funding of capital projects done by Milwaukee County largely due to the sales tax collection by the county which in the old days was intended to pay the capital costs of long term borrowing–this was a good policy and allowed the county to pay for use of a facility over the long term use instead of one time, all at once financing. The Abele administration has changed this policy away from long-term bonding in favor of cash financing. This will put a burden on Marcus (along with other Cultural and Park facilities) to pay out of revenue since there is no ability for property taxes or reduced shared revenue from the state to pick up this cost. This is another example of Milwaukee County paying for regional assets.