The Rise of a Partisan Supreme Court

It’s supposed to be non-partisan. How and why did this change?

![Wisconsin Supreme Court. Photo by Royalbroil (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://urbanmilwaukee.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Wisconsin_Supreme_Court.jpg)

Wisconsin Supreme Court. Photo by Royalbroil (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

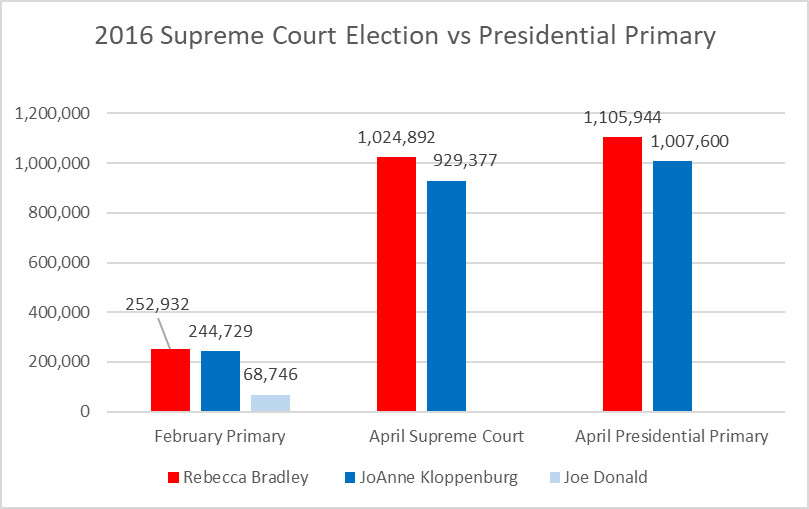

Recently, however, judicial elections—particularly for the state supreme court—have effectively become partisan elections. The graph below shows the vote in the 2016 judicial election.

Two conclusions seem obvious. First the large jump in turnout between the February primary and the April general election was generated by the simultaneous presidential primary. Second, a key reason JoAnne Kloppenburg lost is because turnout in the Democratic presidential primary was less than turnout in the simultaneous Republican primary. This spring’s election for Supreme Court is shaping up as more of the same, with the outcome likely based on turnout.

The Supreme Court race has become increasingly partisan since the Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce, long a non-partisan pro-business group that changed into a pro-Republican group, began spending millions to elect conservative candidates like Annette Ziegler (in 2007) and and Michael Gableman (2008).

I submit that the liberal/conservative or Republican/Democratic dichotomy that has arisen in judicial elections serves Wisconsin poorly. Much more relevant is whether a judge has a passionate desire for the truth.

The effort to shut down the John Doe investigation of coordination between the Scott Walker campaign and various ostensibly independent groups owes its success to the ability of the investigation’s opponents to convince several judges to accept a myth: that so-called “independent” groups are free to coordinate their efforts with candidates so long as they don’t explicitly endorse the candidate (or the defeat of the opponent).

This myth was exploded by a unanimous 3-judge panel of the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals, writing:

… the Supreme Court has stated repeatedly that, although the First Amendment protects truly independent expenditures for political speech, the government is entitled to regulate coordination between candidates’ campaigns and purportedly independent groups.

Later the panel added:

… No opinion issued by the Supreme Court, or by any court of appeals, establishes … that the First Amendment forbids regulation of coordination between campaign committees and issue advocacy groups …

“Issue advocacy” is a term often used to identify political communications that don’t explicitly endorse a candidate. Despite the innocuous-sounding name, it can be applied to communications that are highly partisan. (See this 2014 Data Wonk column for a more detailed discussion of the Supreme Court’s rulings related to coordination.)

Despite the lack of support in the US Supreme Court’s election funding decisions, the myth that the First Amendment forbids regulation of coordination between campaign committees and issue advocacy groups lives on. David Rivkin, the lead attorney for those intent on closing down the Doe investigation, had substantial success in convincing several judges that it represented an accurate interpretation of the US Constitution. The reasons for Rivkin’s success seem to have varied from judge to judge:

- A retired judge newly appointed to oversee the investigation, Gregory Peterson, appeared reluctant to make his own legal analysis. Instead his opinion referred to Rivkin’s brief as “particularly helpful.”

- The next judge to weigh in, now-deceased federal district Judge Rudolph Randa, appeared to have found the groups under investigation far more sympathetic than the investigators.

- The four members of the Wisconsin Supreme Court who ended the investigation by adopting Rivkin’s theory may have had a variety of motivations. At least two (Gableman and David Prosser) may have been personally at risk from the investigation, apparently having themselves coordinated with the same groups suspected of coordinating with the Walker campaign. All had benefitted from the spending of these groups.

Not every conservative judge bought into Rivkin’s theory. Judge Frank Easterbrook, who wrote the Court of Appeals decision rejecting the theory, was nominated by President Reagan and is widely regarded as conservative. The late Justice Patrick Crooks, who leaned conservative, wrote a blistering dissent, accusing his colleagues on the Wisconsin Supreme Court of “erroneously concluding that campaign committees do not have a duty under Wisconsin’s campaign-finance law … to report receipt of in-kind contributions in the form of coordinated spending on issue advocacy.”

The John Doe investigation will continue to echo in the future. It is a handy test for whether judicial candidates put a priority on the truth and can think for themselves. For example, Michael Screnock is running for the Wisconsin Supreme Court in this spring’s election. Screnock is clearly a conservative, having been arrested for blocking an abortion clinic and helping, as an attorney with Michael Best, to develop Wisconsin’s Republicans-favoring gerrymander. Yet he argues that, if elected, he can put aside his partisan preferences and rule based on law.

The Doe investigation offers a useful test of his assurance. When asked by the Journal Sentinel about the Doe investigation, he responded that the court found prosecutors could not investigate activities that that are not illegal. “Do I think that’s an accurate statement of the law? Yeah.” His willingness to repeat Rivkin’s myth does not bode well for his commitment to independently search out the truth.

Skeptics may argue that the effect of unlimited contributions is minimal. Campaigns for federal office have lived with these restrictions for years. To get around the restrictions, they establish an ostensibly-independent “Super PAC,” staffed by operatives who are close to the candidate, understand his or her thinking, and don’t need to consult with the official campaign. However, this arrangement is at best cumbersome and at worst fatal to the campaign. One theory about the quick demise of Walker’s 2016 presidential campaign is that by losing his former campaign manager to his Super PAC he lost his most trusted advisor.

Finally, shutting down the Doe investigation may turn out to be a test run to shutting down Robert Mueller’s investigation of Donald Trump’s ties to Russia. Rivkin was initially a Trump opponent but more recently has become a Trump enabler. He argued in the Washington Post that its unrealistic and unfair to make Trump use a blind trust. In the New York Times, Rivkin argued that the justice department and FBI should investigate Democrats.

A Times article about the possibility of Trump shutting down the investigation of Russian influence on the election quoted Rivkin:

As a policy matter, I would’ve said a few months ago that it was a bad idea. But with what’s going on in the Russia investigation, I am not sure that this is true anymore.

Recently Rivkin argued in the Wall Street Journal that Trump could issue a mass pardon to those caught up in the investigation:

A president cannot obstruct justice through the exercise of his constitutional and discretionary authority over executive-branch officials like Mr. Comey. If a president can be held to account for “obstruction of justice” by ending an investigation or firing a prosecutor or law-enforcement official — an authority the constitution vests in him as chief executive — then one of the presidency’s most formidable powers is transferred from an elected, accountable official to unelected, unaccountable bureaucrats and judges.

Once Wisconsin was known as the pioneer of reforms that made both the state and the nation more democratic. Nowadays Wisconsin’s influence on the national character seems almost the contrary.

Data Wonk

-

Why Absentee Ballot Drop Boxes Are Now Legal

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

The basic reason that the judiciary has become partisan is that making it so serves the interests of certain groups. These groups are best defined as reactionaries, whose goals are to reverse the two waves of social progress achieved in the last century. The first wave were the “social safety net” gains begun in the New Deal, and the second, the extension of basic rights and those other gains to groups that were excluded in the past (women and black, handicapped and lgbt people), via the Civil Rights Acts and related legislation. Of these racial animus was – and remains – the most potent force.

Reactionaries, a combination of corporations, rich people, racists and nativists, have played a very intelligent long game. The current reactionary era started with white backlash, and morphed into the most powerful political force in the country, finding ways to insert people like Scott Walker and now Donald Trump into office in what seems like the terminal phase.

Getting control of the courts was an integral part of the the overall plan, as the recent Supreme Court charade demonstrated. At some point, the legitimacy of the courts gets called into question, but by then, it may be, who cares, since nothing can be done. In an old television western, a corrupt judge asked Cheyenne Bodie if he was showing contempt for the court. Cheyenne replied, “No judge, I’m trying to hide it.” We may not be far away. The crooked judge still had the power to throw Cheyenne in jail.

Alfred North Whitehead, an expert on social progress and reaction, once said, “It is the first step in sociological wisdom, to recognize that the major advances in civilization are processes that all but wreck the societies in which they occur.” That used to feel like an exaggeration.

LMAO! When has the court not been partisan? Or is it only partisan when it goes against what you want? You politicals are comical.