Opioid Crisis Hits City Hard

County’s huge increase isn’t just suburban whites, city and minority residents hurt, too.

The burial of Thomas “TJ” Rivas, one of 260 individuals to die of opioid overdoses in Milwaukee County in 2017, was posted on the MKE Heroin Diaries Facebook page. Screenshot from Facebook.

If the opioid epidemic is a suburban problem, someone forgot to tell Gidget DeLaTorre, 51. She’s lost two close friends to overdoses in the past 10 months and her son sits in prison, after his life spun out of control due to an opioid addiction. All of them grew up on Milwaukee’s South Side.

In August DeLaTorre attended the funeral of Kaela Bradley, a mother of three who spent her last days in a coma at St. Luke’s Hospital as doctors unsuccessfully attempted to save the four-month-old fetus she was carrying. Just a few days before she overdosed, DeLaTorre said, Bradley was sober as they spent the day cooking, laughing and talking about life.

“It (opioid addiction) can happen anywhere and it can be anybody. We’re not talking about homeless people or junkies on the streets. Kaela was a sweet, caring person who lit up the room,” DeLaTorre said.

Bradley was 31 years old when she took a fatal dose of fentanyl, an extremely potent synthetic opioid commonly sold as — or added to — heroin. Fentanyl can be 50 times more potent than heroin and users are often unaware they’re taking it, experts say. Bradley was one of 260 residents in Milwaukee County to die of an opioid overdose, more than 100 of which involved fentanyl, from Jan. 1 through Oct. 15 of this year, according to data from the Milwaukee County Medical Examiner’s Office.

Opioid overdoses account for 84 percent of the 309 drug-induced deaths recorded in the county during that time period. Seventeen individuals lost their lives during a one-week period in June, and 34 died as recently as September.

Bradley’s residence was listed on North Palmer Street, in the 53212 ZIP code that encompasses the Northeast Side, including Riverwest. Sixteen residents in 53212 have died from opioid overdoses so far in 2017. Twenty-four residents of the 53204 ZIP code area where Bradley grew up and spent much of her time died from opioids, and the adjoining 53215 ZIP code area lost 19 people. Those three neighborhoods, along with the 53209 Zip code, have the highest number of residents who died from overdoses and account for nearly 30 percent of opioid deaths in the county in 2017.

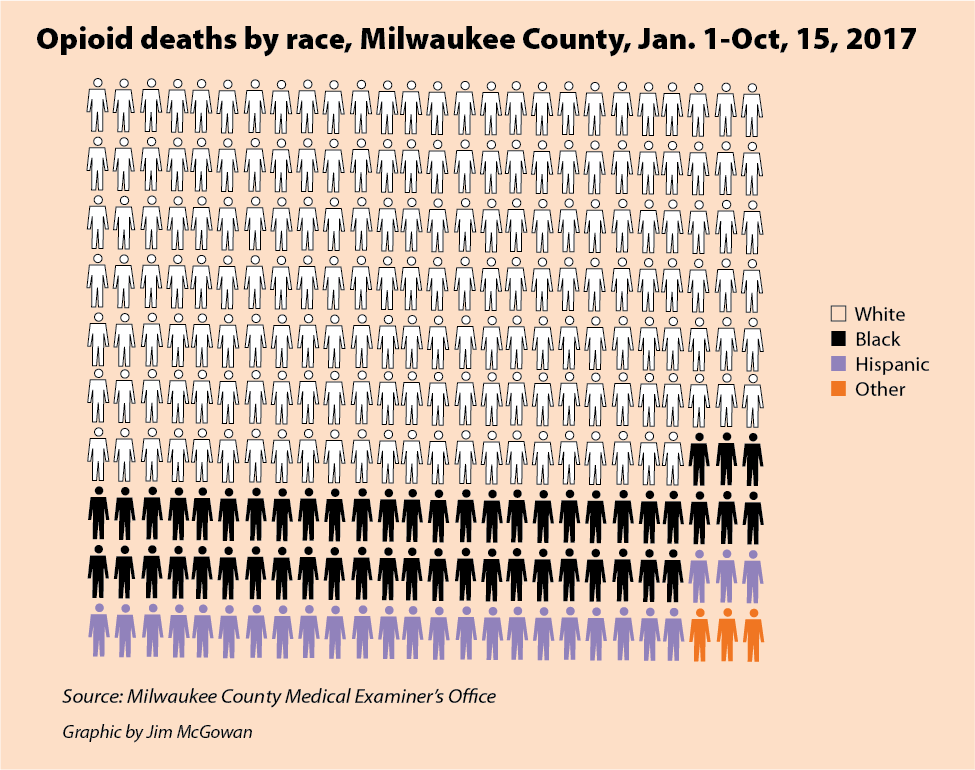

Sixty-eight percent of individuals who died were white, 20 percent were black and 10 percent were Hispanic (see graphic, below); 70 percent lived in the City of Milwaukee while the remainder resided in the suburbs or other cities.

That significant numbers of central city residents and minorities die of opioid overdoses is no surprise to Rafael Mercado, who helped create the Facebook page MKE Heroin Diaries after losing four cousins to opioids within a year. Mercado posted video of the burial of his cousin, Thomas “TJ” Rivas, on the MKE Heroin Diaries page as a tragic example of the damage that opioids cause, he said.

“We’re doing whatever we can to help people become more aware. We need to unite if we’re going to deal with this crisis and get people the help they need,” Mercado said.

The page also features news articles, personal stories and information about upcoming events, including trainings about Narcan, a prescription drug that reverses the effects of opioids. According to Rivas, for every death that has resulted from opioid abuse, another eight people were saved by Narcan.

The Facebook page also facilitates what Mercado calls “warm handovers,” in which opioid addicts are accompanied to a treatment facility.

“We don’t just drop them off at the door; we hold their hand and walk them through,” said Mercado, who also helps organize bi-weekly needle clean-ups, many of which occur on the South Side. Unfortunately, said Mercado, treatment options in the city are limited, as most rehabilitation centers are in the suburbs.

Few treatment options

There aren’t enough treatment facilities available in Milwaukee to deal with the enormity of the addiction crisis, said Sarah Pollack, communications manager at Meta House. Founded in 1963 primarily to treat alcoholism, Meta House is a drug and alcohol treatment facility for women located at 2625 N. Weil St. The program houses 35 women and 15 children in a former rectory located behind the main offices. It also has 25 off-site apartments for women, and provides outpatient services.

Still, the number of women Meta House serves, 80 percent of whom complete treatment and have successful recoveries, is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to addressing addiction among women in the city, according to Pollack. She said that 28,000 women are struggling with addiction in Milwaukee and only one in 10 are receiving treatment. Women have accounted for one-third of the opioid deaths in Milwaukee County so far in 2017 (see graphic, below). There has also been a stark increase in the number of women struggling with heroin or other opioid addictions in recent years, she said.

“It’s progressively gotten worse, and the stakes higher as we see increased loss of life in our community, Pollack said.

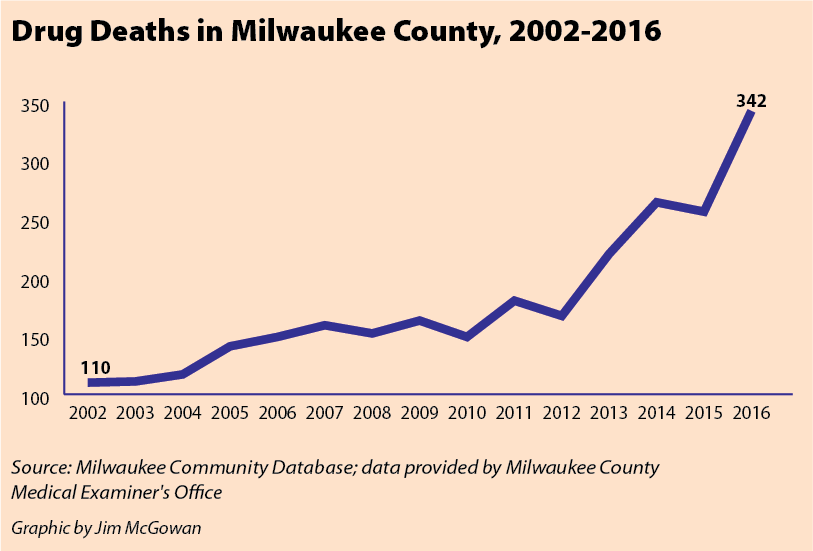

According to data provided by the Medical Examiner’s Office to the Milwaukee Community Database, the number of drug deaths in the county has increased from 110 in 2002 to 342 in 2016 (see graphic, below).

Most of the women who arrive at Meta House for treatment are survivors of past trauma, and are caught in a cycle of poverty, Pollack said. The two-generation treatment approach addresses addiction and additional challenges women face such as lack of childcare, housing or employment. Children of patients are offered counseling and other services meant to help them overcome trauma and understand how addiction functions, in hopes that they will avoid the disease down the road. But the biggest challenge is getting women to come through the doors, Pollack said.

“Nothing about getting treatment is easy, but reaching out for help and facing your challenges head-on is a brave thing to do,” added Pollack, who cautioned against stereotypes often associated with drug users. Many of their addictions began quite innocently, she said, a result of legal prescription medication usage.

“I had one woman who was at a bonfire and was accidentally burned from head to toe. To manage the pain she was prescribed opioids and became addicted,” Pollack said.

The prescriptions run out, but addiction remains, forcing many to turn to the streets for prescription pills such as Vicodin, Percocet or Oxycodone, she said. Once the prescription pills become too expensive, people with addictions resort to buying $10 hits of heroin on the streets of Milwaukee, she added.

Focus on opioids

The growing epidemic has garnered increased attention nationwide, following President Donald Trump’s declaration on Oct. 26 that opioid addiction is a “public health emergency,” and his pledge of federal resources to combat the problem. Though the declaration was a “step forward,” wrote Wisconsin Sen. Tammy Baldwin and 18 other senators in an open letter to Trump, it only made available $57,000, “which fails to adequately address this epidemic.”

“More action must be taken in order to craft a timely and effective national strategy that will achieve long term solutions to this crisis. Specifically, we are concerned that your declaration does not yet include any additional funding resources for key programs and initiatives that will help our patients, providers, first responders and researchers who desperately need more assistance,” said the letter.

Since Trump’s announcement, the city, county and state have beefed up their efforts to address the opioid crisis. Last week the Milwaukee County Board of Supervisors voted 18-0 to allow county lawyers to hire outside counsel to take legal action against pharmaceutical manufacturers. The companies are contributing to opioid deaths and creating millions in unexpected costs for first responders, hospitals and law enforcement, among others, said County Supervisor Peggy West, adding that 80 percent of heroin users started on prescription painkillers.

West said the Medical Examiner’s office has seen such a large increase in opioid overdoses that the 2018 Milwaukee County budget includes funds for a $380,000 machine that speeds up toxicology processing.

“The loss of life has been so dramatic that it’s very difficult to find someone who doesn’t know someone who has died from an overdose,” West said.

Rafael Mercado holds a container of syringes collected during a recent needle clean-up on the South Side. Photo by Edgar Mendez.

The county’s 2018 budget also includes $1.1 million in funding to target the opioid crisis. Those efforts are a start, but not nearly enough, said West, who is pushing the county and state to think outside the box to stem the epidemic.

“We need to look at why people use drugs and try to assist them,” West said. She was the author of an amendment adopted Monday, which would create a workgroup to explore the creation of Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse (AODA) treatment pods at the County’s House of Corrections in Franklin.

Earlier this year, a City-County Heroin, Opioid and Cocaine task force was created in response to the crisis. The task force hosted two listening sessions in late October seeking public input as it crafts a comprehensive plan to fight opioid addiction. Ald Michael Murphy, a member of the task force, said coordination among different entities is crucial, as the city currently lacks financial resources to deal with the epidemic. Only $25,000 in funding to deal specifically with opioids was allocated this year, according to Murphy, who said he has personally helped raise more than $100,000 to combat the problem. He said the city will increase funding to $75,000 in 2018.

“It’s unfortunate, but not a lot of city resources are going into dealing with the opioid issue. There’s still this stigma of people viewing it as an individual problem and one where people can quit if they want,” Murphy said.

The loss of life has been most devastating, said Murphy, but the impact of opioid abuse can also be felt across the city through increased property crime, rolling drug houses, violence related to battles over drug turf and the economic loss from the people who died or are unable to work due to addiction.

“Then you think about the children who are suffering from abuse or neglect due to addictions and even the young people who are gaining access to opiates and dying,” Murphy said. Since 2002, 15 children age five and under have died from opioid overdoses. Three deaths occurred this year and nine since 2012.

According to Murphy, the task force’s short-term goal is a targeted social media campaign directed towards at-risk demographic groups. It also plans to work with the Medical College of Wisconsin to identify and implement best practices in reducing opioid addiction. The five-year goal, said Murphy, is to greatly reduce the number of addicts and deaths locally. The city is also considering whether to join the county in its effort to bring a lawsuit against pharmaceutical companies or even file a lawsuit of its own, he noted.

“The only silver lining in all of this is an increased public discourse and a changing attitude in addressing opioid addiction and the stigma attached to it,” which didn’t occur during the crack epidemic of the 1980s, acknowledged Murphy.

Sarah Pollack, communications manager at Meta House, stands next to a board filled with slogans for women in treatment. Photo by Edgar Mendez.

“I wasn’t around for that debate, but certainly the discourse and discussion has changed dramatically since this epidemic hits mainly the white person,” he added. Still, he said, the loss of life due to drugs is dramatically higher than ever before and deaths cut across all races.

The state is also getting into the act, recently announcing the renewal of a federal grant of $7.6 million for 2018, to be used to boost opioid prevention, treatment and recovery efforts. Plans for the federal funds, according to a statement from Gov. Scott Walker, include expanding access to opioid-disorder treatment; hiring and training recovery coaches; and creating at least three new opioid treatment centers in the hardest-hit areas of the state. The state is also providing additional resources in its biennial budget for county child welfare services, which have had a significant increase in caseloads due to the opioid crisis, according to the 2016 state report, “Combating Opioid Abuse.”

Walker, who recently announced that he will seek a third term as governor, also signed a bill last week that allows law enforcement officials to charge those who manufacture and sell variations of fentanyl. Those variations, commonly referred to as “fentanyl analogs,” hadn’t previously been listed as illegal substances, and are being created legally in labs, according to experts. Assembly Bill 335 makes possessing, dealing or manufacturing all variations of fentanyl a felony.

All these efforts are too late for Kaela Bradley, the 259 others who’ve died of opioid overdoses this year in Milwaukee County and the hundreds before them. Bradley’s Facebook page is now a memorial, filled with posts from friends and photos, including many of her with her children and one in which she’s proudly holding the medallion she received for reaching the 60-day mark of sobriety.

In the “About Me” section of her Facebook page, Bradley wrote, “A great mother fighting and recovering the disease of addiction and I’m not ashamed to admit it. I am putting my life and my family back together. I will suceed (sic).”

And though Bradley lost her battle with addiction, DeLaTorre said she doesn’t want that to be what she is remembered for. “She was a mother, a daughter, and a great friend. Kaela was a beautiful person.”

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on eighteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.

More about the Opioid Crisis

- Attorney General Kaul Announces Consent Judgment with Kroger Over Opioid Crisis - Wisconsin Department of Justice - Mar 21st, 2025

- Baldwin Votes to Strengthen Penalties, Step Up Enforcement Around Deadly Fentanyl - U.S. Sen. Tammy Baldwin - Mar 17th, 2025

- Wisconsin Communities Get Millions From Opioid Settlement as Deaths Decline - Evan Casey - Mar 1st, 2025

- MKE County: County Creates Easy Public Access To Overdose Data - Graham Kilmer - Feb 18th, 2025

- Milwaukee County Executive David Crowley and the Office of Emergency Management Launch New Overdose Dashboard - County Executive David Crowley - Feb 18th, 2025

- Fitzgerald Advances Legislation to Fight Opioid Epidemic - U.S. Rep. Scott Fitzgerald - Feb 6th, 2025

- Milwaukee Is Losing a Generation of Black Men To Drug Crisis - Edgar Mendez and Devin Blake - Jan 31st, 2025

- Milwaukee County’s Overdose Deaths Declined For Second Straight Year - Evan Casey - Jan 27th, 2025

- MKE County: United Community Center Awarded Drug Company Money For Addiction Treatment - Graham Kilmer - Jan 12th, 2025

- DHS Provides Update on Distribution of Latest Opioid Settlement Funds - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Jan 9th, 2025

Read more about Opioid Crisis here

Political Contributions Tracker

Displaying political contributions between people mentioned in this story. Learn more.

Ok–I live in 53204 and see syringes on the ground. What am I supposed to do with them? We tell children to find an adult–I am an adult–and I am unclear here. There are no red box//hazardous/medical waste trash containers ANYWHERE in 53204 that I am aware of. Just placing an open (uncapped) needle into a trash can then endangers the trash collectors. Then you have to worry about fentanyl–and you have to wear gloves to even pick up the needles. When I see a needle in MY hood, what am I supposed to do? I am NOT carrying it back to my house to mix in with my trash.

Republican red states like Wississippi have failing economies with few to no good jobs as well as huge opioid epidemics but democratic blue states all have booming economies, legal cannabis and thus far fewer opioid overdose deaths. Same goes for all the drunkards in Wississippi.

I just wanted to preemptively respond to drunk pill popping hypocrite Wisconsin faux Conservative Digest before he gets his undies all up in a bunch. No hemp or cannabis is not heroin nor does it kill maim or destroy like your rot gut liquor and poison opioids do. Go troll somewhere else.