City’s Revenue Structure Is “Broken”

Milwaukee’s over-reliance on property tax, state aid threatens its future, study warns.

Over the long period that Henry Maier served as Milwaukee’s mayor, from 1960-1988, probably no issue was more important than state shared revenue to the city. Maier was relentless in lobbying legislators, famous even for attacking Democratic lawmakers from Milwaukee, and was chief founder of a special lobbying group, the Alliance of Cities, to push for more revenue to the bigger cities. (The group disbanded some years ago.)

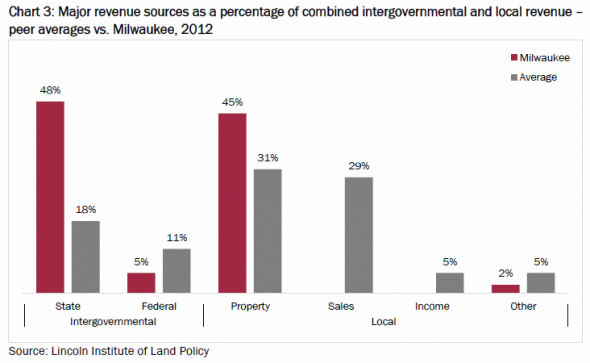

A new study by the nonpartisan Public Policy Forum (PPF) helps explain Maier’s obsession: his city was uniquely dependent on state aid compared to others nationally. In those days well more than half the city’s budget came from state shared revenue. Even today, after 20 years of declining state aid, the city still gets 48 percent of its revenue from this source, compared to just 18 percent for 38 peer cities analyzed in the study. “General state aid historically has been Milwaukee’s largest revenue source,” the new study notes.

Which is why its huge decline since the mid-1990s is a fiscal earthquake. “If Milwaukee’s intergovernmental revenue… had increased at the rate of inflation from 1995 to 2015,” the study notes, “then its revenue total would have been 58% higher ($415 million versus the $264 million it actually received).” In real dollars that’s a loss of $151 million — a huge hole for a city whose current budget for basic services is $834 million.

Milwaukee has no chance to replace this lost funding with local taxes, because it is uniquely constrained, compared to peer cities. “No other state in the Midwest has a local tax structure like Wisconsin’s that relies solely on the property tax,” the study notes. “Most other cities get about a third of their revenue from a local sales or income tax or both,” but Milwaukee gets nearly 90 percent of its local revenue from the property tax and is prevented by state law from levying other taxes. More recent state laws also constrains how much the city can increase the property tax.

As a result, the study notes, Milwaukee’s property tax increases made up for less than 20 percent of the huge decline in state funding since 1995.

The state’s straitjacket on city taxes, as I’ve written, goes back to when Wisconsin was the first to create an income tax, in 1911 (two years before a constitutional amendment created the federal income tax). State leaders feared “balkanization” of the state — cities competing with each other based on taxes — so the legislature instead promised to funnel back most of the state income tax to municipalities in the form of state shared revenue.

But that’s ancient history by now and state leaders in both parties no longer seem to care about it. There has been a bipartisan trend of lowering state shared revenue for more than two decades now and that has been killing the state’s biggest city and beneficiary of state aid.

A September 2016 follow-up study found that smart governance, including “successful efforts to dramatically reduce health care costs, stabilize pension contributions, and trim the active workforce” had allowed the city to forestall the fiscal cliff it faced, but did nothing about the long-term structural problem. “The City’s revenue structure – which has been imposed upon it by the State of Wisconsin – remains broken,” the PPF concluded.

Or as the group’s current study, released yesterday, warns: “There has never been a more urgent and better time for City and State leaders to consider whether a revenue structure established more than a century ago still is meeting the needs of Milwaukee citizens and taxpayers.” If not addressed, it notes, Milwaukee’s leaders will not be able “to invest appropriately in areas ranging from the Police workforce, to neighborhood revitalization, to replacement of the Milwaukee Water Works‘ lead service lines.”

The group’s latest analysis — of 38 peer cities — was done both to dramatize how uniquely constrained Milwaukee’s finances are, and to explore possible solutions that have worked in other cities.

While other cities use a wide range of approaches, they tend to have two things in common. First, the use of two or more major taxes rather than just the property tax “they can spread the cost of their expenditures across multiple forms of local taxation and, thereby, maintain lower property tax rates,” the PPF notes, adding that Milwaukee has the second highest “effective” property tax rate of any city analyzed by one national study.

Secondly, other cities adopt a tax that spreads the costs to tourists, workers from the suburbs and others who benefit from city services and amenities. “As cities increase in size, they become more cosmopolitan,” the study notes, “and host greater numbers of non-residents who are engaged in business, employment, tourism, entertainment, etc.” A local sales tax “enables local governments to recoup the costs of services provided to all users irrespective of their purpose for being in the city.”

Major revenue sources as a percentage of combined intergovernmental and local revenue – peer averages vs. Milwaukee, 2012.

A local sales tax is the most popular second tax for other cities: on average they get 29 percent of their revenue this way. “Cities with larger populations tend to draw more heavily on the sales tax and less upon the property tax,” the study notes.

But a city like Cleveland has a local income tax, and its officials estimate that 87 percent of it is paid by “people who work in the city but live outside of it,” the study notes. It has also become a way to weather declining state aid: “Cleveland’s mayor cited the City’s annual loss of state revenues as a primary justification for his proposal to increase the City’s income tax from 2 to 2.5%.”

Kansas City has a 1 percent tax on the city earnings of all residents and non-residents, as well as on business net profits. Pittsburgh has a payroll tax it charges all private employers in the city, a local service tax on every employee and a parking tax charged at all public and private parking lots and garages “to ensure that daily non-resident commuters pay for a share of the City services they use,” the study notes.

While the study notes the advantages and disadvantages of any added tax, it’s hard to imagine a city income tax getting approved: it “would be a difficult pill for Milwaukee to swallow given the State’s already high income tax rates,” the study notes.

By contrast, a local sales tax, even as high as 1.5 percent, would still leave Milwaukee with a tax lower than the median for its peer cities. And while a sales tax is regressive, the state exemption on groceries and prescription drugs helps alleviate the problem, while the tax is very effective at charging all users of city services and amenities.

The 2007-09 budget of Governor Jim Doyle would have allowed Milwaukee to levy a 0.5 percent sales tax under the state “Premier Resort Area Tax” statute (which currently allows selective areas, like Wisconsin Dells, to charge this tax). The tax “likely would apply only to a limited geographic area (the Doyle proposal covered a four-square-mile section in and around downtown),” the study notes, but “this approach could begin to move Milwaukee toward revenue diversification” and “begin to tap into Downtown Milwaukee’s impressive renaissance.”

Whether this reform or some other is the best approach, it’s crystal clear that something is needed because the revenue model for Milwaukee is broken and has been for many years, as three separate studies by the sober minded PPF analysts have now concluded. It’s time for the state legislature to recognize the problem and start working toward solutions, as other states have.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits, all detailed here.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

More about the Local Government Fiscal Crisis

- Mayor Johnson’s Budget Hikes Fees, Taxes In 2025, Maintains Services - Jeramey Jannene - Sep 24th, 2024

- New Milwaukee Sales Tax Collections Slow, But Comptroller Isn’t Panicking - Jeramey Jannene - Jun 28th, 2024

- Milwaukee’s Credit Rating Upgraded To A+ - Jeramey Jannene - May 13th, 2024

- City Hall: Sales Tax Helps Fire Department Add Paramedics, Fire Engine - Jeramey Jannene - Jan 8th, 2024

- New Study Analyzes Ways City, County Could Share Services, Save Money - Jeramey Jannene - Nov 17th, 2023

- New Third-Party Study Suggests How Milwaukee Could Save Millions - Jeramey Jannene - Nov 17th, 2023

- Murphy’s Law: How David Crowley Led on Sales Tax - Bruce Murphy - Aug 23rd, 2023

- MKE County: Supervisors Engage in the Great Sales Tax Debate - Graham Kilmer - Jul 28th, 2023

- MKE County: County Board Approves Sales Tax - Graham Kilmer - Jul 27th, 2023

- County Executive David Crowley Celebrates County Board Vote to Secure Fiscal Future and Preserve Critical Services for Most Vulnerable Residents - County Executive David Crowley - Jul 27th, 2023

Read more about Local Government Fiscal Crisis here

Murphy's Law

-

National Media Discovers Mayor Johnson

Jul 16th, 2024 by Bruce Murphy

Jul 16th, 2024 by Bruce Murphy

-

Milwaukee Arts Groups in Big Trouble

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Murphy

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Murphy

-

The Plague of Rising Health Care Costs

Jul 8th, 2024 by Bruce Murphy

Jul 8th, 2024 by Bruce Murphy

What about the reports put out by RightWisconsin regarding the conservative MacIver Institute claiming that Milwaukee’s debt service is way out of whack? Since it is a partisan piece, they fail to go into details about what exactly the city is borrowing for, but they do point out that from 2004-2015 the city is borrowing 3x’s annually (increasing from 90 to 285 million). They also claim the city is bringing in 1.26 billion dollars in revenue a year while expenses, excluding debt service, is 1.06 billion. So in theory, as they claim, the current revenue should be enough and then some.

I’d love to hear a counterpoint to that from those who are pushing the city revenue troubles story.

Is MacIver saying PPF is wrong? Are they responding to the new report? As you say you have to consider the source here. Or sources. One is nonpartisan and the other is rabidly partisan.

More Baloney: Only thing broken here is the white, liberal, male, racists that run Milwaulee and people like Murphy who are their apologists.

They cannot raise enough money cause they put it all into pensions, bennies, salaries for their buddies for votes.

Lousy managemetn, top ten worst in the country,y and top ten worst for crime. Worst fro schools whose employees are way overpaid for what they accomplish.

That is why everyone blew out to Waukesha to get away from these incompetents.

Walker fixed state after incompetent Lefties wrecked it, but he cannot fix this mess, too much debt, lousy managers, incompetent press and MPS.

we love Milwaukee, Norqusit was good Mayor, so was Maier, but Barrett is joke.

I am completely in favor of letting Milwaukee jack up any and all taxes it wants, to as high as it wants. Wheel taxes, sales taxes, soda taxes, have at it.

Vincent, they bring up a related but not contradictory point. If debt was in line with historical levels (based on their report) then in theory we wouldn’t even need to discuss revenue sources because we’d already have a sufficient level.

22% of San Francisco’s budget comes from the property tax.

San Fran’s property tax rate is also 1/3rd that of Milwaukee. Do we cut Milwaukee’s property tax rate when we decide to diversify revenue sources?

couple factual points here: yes, MacIver is partisan but the Public Policy Forum has always been non-partisan and has a long history as a watchdog on government budgeting, spending, etc. On the city’s pension and benefits, which WCD mentions, the city has been fiscally responsible as PPF study notes. When the county (under Ament) and state (under Thompson) both passed huge and unjustified pension sweeteners, the city (under Norquist) opposed any pension giveaway.

AG- Yes, in fact the PPF assumes cuts in Milwaukee property taxes and shared revenues in their scenarios, and the City still has the same amount of funding. So why won’t suburba-GOPs do it?

AG-I address the MacIver post in tomorrow’s Data Wonk column. They misinterpret the data on debt.

Bruce, does the pension board still expect 7.5 percent returns a year for its pension to its employees, best to my knowledge the city of Milwaukee is the only city of the top 30 that projects such rosy projections. Most cities aim for 6.0 percent returns at best.

Of course MacIver did. No surprise there.

AG, one reason the City’s outstanding debt might increase between 2004 and 2015 is refinancing due to reduced interest rates.

All bonds are either “callable” or “non-callable”. A callable bond is like a mortgage in that it can be paid off early if the borrower (the City) wants. A non-callable bond is more like a bank CD in that the City (or bank) cannot unilaterally decide to redeem early. Issuers, like the City, prefer the flexibility of callable bonds but that flexibility comes with a price—a higher interest rate. So many (most?) bonds, whether government or corporate, are non-callable.

While non-callable bonds cannot be paid off early, they can be re-financed: New bonds are issued (more money is borrowed) at the new lower interest rates. The new money is used to purchase enough US Treasury securities to pay off the old bonds as they come due.

So, on paper, you have increased your debt even though you really haven’t, and (after deducting the money coming from the Treasuries) your debt service has actually dropped.

If interest rates continue to fall, and if the new bonds were also non-callable, the city might refinance the new bonds, too, by issuing a third set of bonds (and buying still more Treasuries, and showing still more outstanding paper debt).

Jason, expecting a long-term 7.5% annual return isn’t out-of-line. The NYC pension fund uses a 7.0% figure and the state of NJ uses 7.65%. According to a mailing I just got from T. Rowe Price, the stock market has averaged an 11.7% annual return (and 8.6% after inflation) between 1928 and 2016.

In comment #8 above, Bruce Murphy wrote, the “state (under Thompson) both passed huge and unjustified pension sweeteners.”

I was an unexpected beneficiary of one of those pension sweeteners by the state. In the late 90s, Thompson and the legislature, passed a law to double the accumulated unused sick time upon retirement to encourage workers not to take fake sick time for Brewer’s openers or deer hunting. I didn’t abuse my sick time and I had 1200 hours worth of time when I retired in 2000. This was doubled to 2400 hours, enough to get me paid up health insurance for 4 years.

This wasn’t the only abuse of this system. Many, maybe even most, of the legislators never took a sick day. I believe they are given 13 days a year. Professors didn’t take sick days as long as they had colleague coverage, someone else to teach their class. I think the college administrators similarly abused the system.

Long term legislators will have cadillac health insurance from the State of Wisconsin for life, after they finally retire.

The state has been removing wealth from Milwaukee almost through its entire existence. Through sales and income tax and fees, billions have been taken. Milwaukee taxes and fees supported the state for most of its existence. The same with Federal taxes. Both have been a economic drain to cities like Milwaukee.

Milwaukee Metropolitan and Madison City and Dane County would do fine economically without the remainder of Wisconsin if it were allowed to retain all the tax monies that are removed on an annual basis.

Milwaukee’s problem is not money it is leadership. They have plenty of money. If they had more it would just go to bigger paychecks, bennies etc to the people they pay off to get elected.

MPS spend more than anyone fro worse result. A ” national “disgrace” according to Arne Duncan. One of the ten worst run cites in country, with more crime percapita then Chucgo.