Reservoir Ave. Was Font of City’s Water

And part of street, now named Glover, celebrates the freeing of famed fugitive slave.

When Solomon Juneau planned his new village of Milwaukee in 1835, there were only a handful of permanent residents in what would become known as Juneautown. Thirty years later the village, combined with the villages of Kilbourntown and Walker’s Point, had become a city of 70,000 people. The wells supplying water for drinking and cooking were inadequate for so many citizens. Some wells were infected with bacteria from the human waste that had seeped in, helping to spread diseases in the community. There was not enough water to put out the many fires common in an era of wooden buildings nearly touching one another on narrow lots. Some prime real estate was not being developed because wells could not satisfy the need for water.

To remedy the situation, a massive water works project was begun in 1871. In order to supply the city with water, a reservoir was needed atop a high point where gravity would draw water through pipes to supply homes and industry. The hill on North Avenue between Booth and Bremen Streets was chosen, on land that had been donated by Byron Kilbourn, the founder of Kilbourntown.

The project, with many miles of water pipes installed throughout the city, was completed in 1874 to rave reviews. It solved many problems. Residents and industry had a cleaner and more than adequate water supply. A professional fire department had recently replaced the volunteer force and it now had easily accessible water to fight fires. Mansions along the lake bluffs were constructed with the new water supply available for the owners’ needs.

The park-like area from the reservoir south to the bluffs above what is now Commerce Street was known as Kilbourn Park or Reservoir Park. A new street between Holton and Booth Streets along the bluff was created by developers and named Reservoir Avenue in 1875. It was extended southwesterly to Beers Street, which the city renamed Reservoir Avenue the same year. (Beers Street had nothing to do with breweries or taverns, it been named in 1837 for Cyrenius “Cyrus” Beers, a Chicago hardware merchant, alderman, and real estate speculator.)

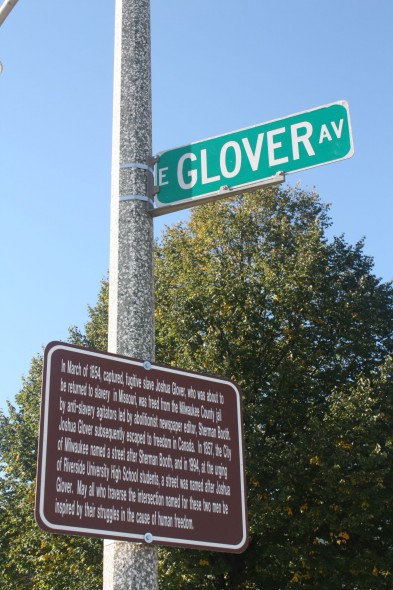

In 1994, a Riverside High School history teacher, Chuck Cooney, and his class were studying the rescue of Joshua Glover. Glover had escaped from his life as a slave in Missouri in 1854. He made his way to Racine, where he was captured by a United States marshal and brought to the jail in Milwaukee’s Cathedral Square to await his return to his former life, as required by the Fugitive Slave Law.

Sherman Booth, a newspaper editor, and thousands of other Milwaukeeans were enraged at the idea that Glover should be forced back into a life of slavery. They marched to the jail, freed Glover and sent him on his way aboard the underground railroad to freedom in Canada. Booth was arrested and charged with breaking the Fugitive Slave Law. For the next seven years, Booth was in and out of court as the Supreme Courts of Wisconsin and the United States argued about the legality of the law. In 1861, an action by President James Buchanan freed Booth.

The students in Cooney’s class thought that Glover should be honored with a street name and they targeted the original section of Reservoir Avenue, between Holton and Booth Streets. Booth Street had been named for Sherman Booth by developer Otis B. Hopkins in 1857 and it seemed appropriate that a street named for Glover should intersect with it.

So the students encouraged residents on the street to sign a petition to rename it. The majority on the homeowners signed and that part of Reservoir Avenue was renamed Glover Avenue. The rest of Reservoir Avenue, which ran west to N. 14th Street and east to Garfield Avenue, retained its name.

As technology changed, the reservoir became unnecessary. It was filled in and the 35-acre Kilbourn Reservoir Park, a historical site, was created. The city-owned park includes recreational activities like sledding, baseball, basketball, and a tot-lot. It is landscaped with native plants.

South of North Avenue, the grounds include a soccer field, urban gardens and Kadish Park, named for Alice Bertschy Kadish, a Milwaukee school teacher and philanthropist. The park amphitheater and terraced landscaping were donated by the Selig, Joseph, and Folz families. The COA Youth and Family centers schedule the free Skyline Music series presented on Tuesday evenings during the summer as well as another popular series, Shakespeare in the Park.

Views from the former reservoir offer a spectacular panorama of the downtown and east side skylines. In 1875 the Milwaukee Sentinel exclaimed “it is beautiful property, and near the mills, tanneries and round house.” It is even more beautiful today since condominiums and apartments have replaced the mills, tanneries and railroad roundhouse and the smoke and unpleasant odors that they produced.

Reservoir Avenue

Carl Baehr, a Milwaukee native, is the author of Milwaukee Streets: The Stories Behind their Names, and articles on local history topics. He has done extensive historic research for his upcoming book, Dreams and Disasters: A History of the Irish in Milwaukee. Baehr, a professional genealogist and historical researcher, gives talks on these subjects and on researching Catholic sacramental records.

City Streets

-

Revised Milwaukee Streets Book Dishes the Dirt

Nov 3rd, 2025 by Michael Horne

Nov 3rd, 2025 by Michael Horne

-

The Curious History of Cathedral Square

Sep 7th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

Sep 7th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

-

Gordon Place is Rich with Milwaukee History

May 25th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

May 25th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

Carl –

Great article. But, I need some help as one geographical reference throws me.

“The rest of Reservoir Avenue, which ran west to N. 14th Street and east to Garfield Avenue, retained its name.”

Reservoir and Garfield are parallel. Shouldn’t the above sentence read “east to Holton Street”?

A Doug who lived his back in the day adolescent years on Booth and North next door to His Honor.

Thanks, Doug. The two streets are parallel until Reservoir intersects with Buffum then it veers to the northeast and terminates at Garfield just before Humboldt.

Carl,

Fine article, it was good to see the Glover Street name change project still of interest. Congratulations on you upcoming book about the Irish in Milwaukee. You might be interested in a piece I wrote about the Irish in Milwaukee for the Encyclopedia of the Irish in America published by the University of Notre Dame Press, 1999, pages 609-611. We are living in California now, but are always happy to hear what’s happening in Milwaukee. Let us know when your book is published. It is a must read for me! Chuck

Best park in the city! Hurray Riverwest!

Sadly, Holton’s role in the Glover rescue is often overlooked. It is no coincidence that Holton and Booth run next to each other. Holton funded Booth’s journalism, and served as treasurer of the committee to defend Booth in court. That, and much more of the abolition movement was due to Holton. He was barely 40 when the street was named in honor of his accomplishments. My hero, Edward Dwight Holton.

Mr. Michael Horne, You are correct, it is no coincidence that Holton and Booth Streets run next to each other. Developer Otis B. Hopkins named them both in 1857. Since Holton is your hero, I invite you to be a guest writer for the City Streets column and write an article on Holton Street. What do you say?