Study Shows Poverty’s Impact on Kids

New UW study shows 20% of test scores deficit due to lags in early brain development.

Hannah Tunney, 2, holds a book while getting a check-up from nurse practitioner Francesca Vash at Group Health Cooperative health care center in Madison. GHC participates in the national Reach Out and Read program, which distributes books to children up to age 5 at each regular check-up. The program is designed to encourage families to develop good reading habits. Photo by Coburn Dukehart of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

Five-year-old Naja Tunney’s home is filled with books. Sometimes she will pull them from a bookshelf to read during meals. At bedtime, Naja reads to her 2-year-old sister, Hannah.“We have books anywhere you sit in the living room,” said their mother, Cheryl Tunney, who curls up with her girls on an oversized green chair to read stories.

Naja and Hannah are beneficiaries of Reach Out and Read, an early intervention literacy program that collaborates with medical care providers to provide free books when families come in for check-ups.

“I learn things that my brain will always know,” Naja said during an appointment at Group Health Cooperative’s Capitol Clinic in Madison.

Naja’s and Hannah’s brains are in critical phases of development, and they are being stimulated by a home environment that prioritizes education.

Naja Tunney, 5, reads a book at the Group Health Cooperative health care center in Madison while her sister, Hannah, 2, gets a check-up. GHC participates in the national Reach Out and Read program, which distributes distributes books to children up to age 5 at each regular check-up. The program is designed to encourage families to develop good reading habits. Photo by Coburn Dukehart of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

But children who do not have this same experience early in life — especially those growing up in poverty — could experience delayed brain development that significantly harms their educational progress, according to recent research by psychology professor Seth Pollak and economist Barbara Wolfe at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Their study is part of a growing body of socioeconomic brain research documenting what Joan Luby, a child psychiatry professor at Washington University in St. Louis, calls “poverty’s most insidious damage” — that poor children are up against their own biological development.

Along with graduate students Nicole Hair and Jamie Hanson, Pollak and Wolfe found that poverty can cause structural changes in areas of the brain associated with school readiness skills.

These parts of the brain are susceptible to circumstances often present in poor households, including stress, unstable housing, nutritional deficiencies, low academic stimulation and irregular access to health care.

To isolate the effects of poverty from other factors, the study included mostly children of educated mothers — 85 percent reported at least some college-level education and 22 percent had some graduate-level education. Families with factors that could negatively affect brain development, such as a risky pregnancy or a history of psychiatric problems, were excluded.

University of Wisconsin-Madison psychology professor Seth Pollak found that poverty can cause structural changes in areas of the brain associated with school readiness skills. Here, he speaks at a meeting of the Legislative Children’s Caucus in Madison in April. Photo by Coburn Dukehart of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

The study examined brain development of 389 mostly white young people ages 4 to 22 with educated mothers. Household income ranged from less than $5,000 to between $100,000 and $150,000. The fathers had similar educational backgrounds.

The findings suggest that while schools have been the focus of reforms aimed at closing Wisconsin’s long-standing racial and economic achievement gaps, efforts perhaps should start much earlier and be directed at raising income levels of poor children.

An estimated 28 percent of the state’s children live below 150 percent of the federal poverty level. Pollak found that income bracket — which for a family of four is $36,450 a year or less — was associated with diminished brain development and learning.

In a 2016 policy statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics calls the amount of child poverty in the United States “unacceptable and detrimental to the health and well-being of children.”

Legislators on both sides of the aisle in Wisconsin are beginning to agree that more needs to be done to help children.

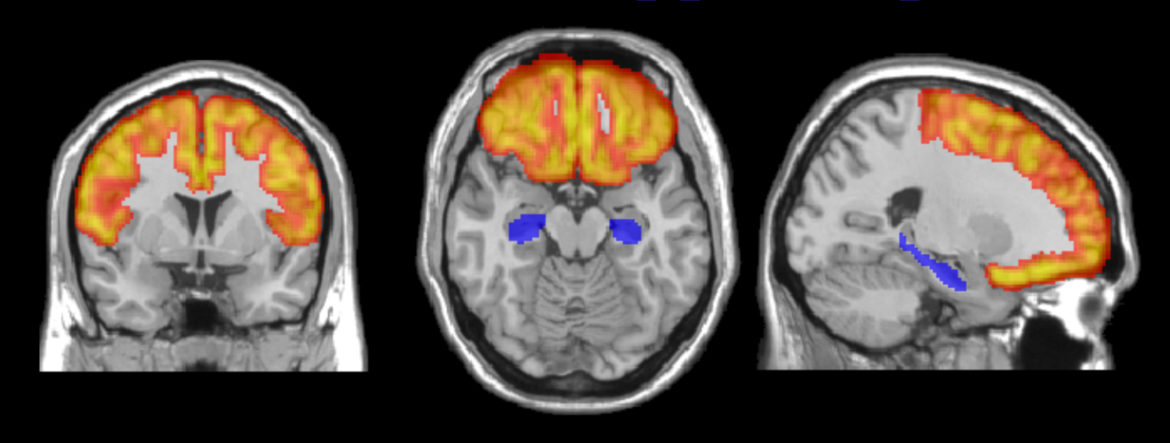

Pollak’s study found that as much as 20 percent of the gap in test scores of low-income children is explained by developmental lags in the frontal and temporal lobes — critical areas of the brain responsible for learning, including attention, emotion regulation, processing complex ideas, memory and comprehension. Children below 1.5 times the federal poverty level scored four to eight points lower on two standardized tests than children who were not poor.

This is an image of an adolescent brain from the study by psychology professor Seth Pollak and economist Barbara Wolfe at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The hippocampus is highlighted in blue, and the frontal lobe is highlighted in orange. Both regions are important for academic achievement, and Pollak and Wolfe and their collaborators have found both can be damaged by child poverty. Image courtesy of Jamie Hanson/Carolina Consortium on Human Development, Duke University.

These tests are the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence and the Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Achievement. On both tests, a composite score between 90 and 110 is considered average.

Researchers also found that children from these poor households have less gray matter — 3 to 4 percent below developmental norms for their sex and age. A larger gap of 7 to 10 percent was found in children living below the federal poverty level, $24,300 for a family of four.

“This is suggesting that there is something about a child’s early environment that is affecting the way their neural systems are working that undermine their ability to extract information and succeed in school,” said Pollak, who is also the director of UW-Madison’s Child Emotion Lab.

Other research has shown a connection between early childhood trauma and “toxic stress” on the ability of children to learn.

Gaps big in Wisconsin

Wisconsin has the largest disparity in the country between the performance of black and white students and the rate at which they graduate. The state also has the highest suspension rates for black high school students in the nation, the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism’s Children Left Behind series reported in December. Despite various local and state efforts, the pattern has not changed much over 20 years.

Wisconsin also has the second-largest poverty gap in the United States between blacks and whites, a disparity that has grown faster than the national average, according to a December report from the UW-Madison Applied Population Lab.

Pollak’s study shows poverty can have biological effects long before children enter the classroom, strengthening the case that efforts to close the achievement gap should begin prior to a child’s first day of school. Given the findings, it is “not really a surprise,” Pollak said, that children from low-income families are doing so poorly.

In 2013, in an earlier study, a team led by Wolfe and Pollak examined how family poverty can affect the rate of brain growth among young children.

They found that infants from lower-income families started life with a similar amount of gray matter to infants whose families were not poor. But by their toddler years, poor children had less total gray matter, they found.

Smaller volumes of brain tissue also were tied to greater behavioral problems in the preschool years, the 2013 study found. The effects of poverty on brain size were strongest among the most impoverished children.

This image shows different fiber bundles in the brain that could be affected by early social neglect. Changes in these pathways may mean information moves less effectively through the brain, resulting in possible problems with memory, attention, visual and spacial skills, planning, thinking and many other ‘higher-order’ executive functions that children need to do well in school. Image courtesy of Jamie Hanson/Carolina Consortium on Human Development, Duke University.

“As infants aged — and presumably had increased exposure to the effects of their environments — the differences in brain volume between poor children and those with greater resources widened,” according to the study.

These studies provide a biomedical explanation for why poor children tend to do worse in school.

“It is the delay of brain development that is accounting for the significant achievement test scores in children living in poverty,” Pollak said. “Now we know that that achievement gap in poverty is at least partially explained by slower brain growth attributed to poverty.”

The effects of poverty on the brain were concentrated among children from the poorest households, those below 150 percent of the federal poverty level. There was no difference between lower-middle-class children and those from affluent families.

“It’s not like we need to get everybody up to affluence,” Pollak said, “we just need to have kids not living in scarcity.”

Article Continues - Pages: 1 2

Children Left Behind

-

Teaching Poor Kids Where They Live

Feb 18th, 2016 by Abigail Becker

Feb 18th, 2016 by Abigail Becker

-

Wisconsin Going Backwards on Achievement Gap

Dec 21st, 2015 by Abigail Becker

Dec 21st, 2015 by Abigail Becker

-

State Has Worst Black-White Learning Gap

Dec 19th, 2015 by Abigail Becker

Dec 19th, 2015 by Abigail Becker