Waukesha Water Plan Leaves Bad Taste

Critics say Great Lakes diversion will feed urban sprawl, cause pollution and lead to more water grabs.

There’s never been a shortage of ideas on how to tap into the waters of the Great Lakes. The world’s largest source of fresh surface water — if spread evenly across the land, the Great Lakes would flood the entire continental U.S. under nine feet of water — these “inland seas” have been seen as a bottomless well for decades by thirsty politicians and clever entrepreneurs.

The latest is a plan by the city of Waukesha to divert million of gallons per day from Lake Michigan through Oak Creek’s water works, then return the same amount of treated wastewater to the lake through pipelines and the Root River, which empties into downtown Racine. A deep aquifer that supplies Waukesha with much of its drinking water has been contaminated with radium since the early 1990s, and, by a court order, must comply with EPA standards by June 2018.

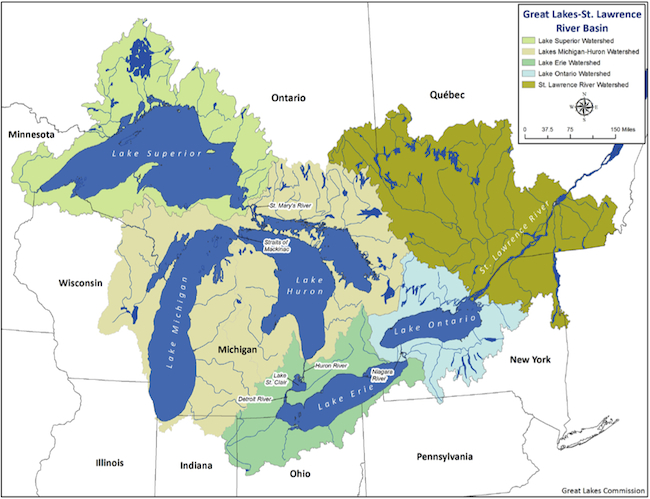

The Waukesha proposal is the first application of its kind under the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact, a 2008 binding agreement passed by Congress that gives the eight Great Lakes states and two Canadian provinces (Ontario and Quebec) authority to manage the Great Lakes basin. Representatives of the Great Lakes governors and Canadian premiers have been debating the merits of Waukesha’s request since it was submitted in January.

Waukesha’s plan is being watched closely across the region and beyond. While the compact restricts water diversions, it allows a few exceptions. Communities and counties that straddle the basin’s boundary line can apply for a diversion, and communities within a straddling county, such as the city of Waukesha, can also apply.

The compact identifies 68 straddling counties throughout the eight-state region. Future diversions would be especially feasible to straddling communities and counties where the boundary of the basin cuts close to water’s edge, principally in Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

Which worries opponents of the Waukesha plan.

“There is a history in the United States of self-determination and self-governance in the area of water rights” by the states that border the water bodies, says Molly Flanagan, vice president of policy at the Alliance for the Great Lakes. Dozens of interstate water compacts have been written to control water flow, floods and pollution. The Great Lakes compact, however, is the first binding agreement to manage the Great Lakes basin. “The Waukesha diversion could undercut that long history of governing water rights.”

As I reported last week in an article for theatlantic.com, revisions to the application have been prescribed by the review panel. But lingering questions remain about the application, which will be fine-tuned by the review panel again on Wednesday before it’s forwarded to the Great Lakes governors for a final vote in June. (Approval requires a unanimous vote by the governors; Canada’s representatives act as advisors and do not vote.)

In meetings I attended in Waukesha and Chicago, the governors’ panel raised questions about the amount of water requested by Waukesha, and the water supply area that would be served. Waukesha originally proposed pumping up to 10.1 million gallons per day by 2050 to an expanded water service area that included portions of the city of Pewaukee and the towns of Waukesha, Delafield and Genesee.

Critics saw supplying water to the outlying communities as a water grab that would lead to more urban sprawl. And last week, to the disappointment of Waukesha officials, the governors’ panel cut the amount to 8.2 million gallons per day and trimmed the water service area to basically include only the city of Waukesha.

Yet, even as the outlying parcels were stripped from the proposal, environmentalists questioned why the governors’ designees hadn’t scrutinized the return-flow of water more rigorously.

Waukesha says its return-flow discharge will improve stream flow and quality to the Root River, with stricter permit limits than existing discharges to the river.

If the diversion is approved and more straddling communities and counties seek diversions, “the end result is not so much an immediate impact on water levels in the Great Lakes, but the return-flow impacts to the lakes — bringing in entirely new sources of pollutants from totally outside the basin,” says Peter McAvoy, a Milwaukee water attorney. “You’re talking about wastewater from a community of 70,000 people, from residential, industrial, commercial sources, and bringing it into the Great Lakes basin from the Mississippi River basin. That is new, that is precedent setting.”

The precedent could weaken the compact, say opponents, opening the door for water-thirsty states in the West and South to make a case before Congress that, because the compact is a federal law, water diversions beyond the basin would be in the national interest.

As one opponent puts it, “States outside of the Great Lakes region will say ‘You guys really aren’t serious about protecting the Great Lakes. You’re all about fueling growth outside the Great Lakes basin, and therefore you ought to allow us to have some of that water, since our needs are so much greater.’”

Racine Mayor John Dickert told me officials in two Arizona communities have already contacted him regarding the possibility of building a Keystone-like pipeline from Lake Michigan to the desert. And there have been no revisions in the Waukesha proposal that would prohibit other Waukesha County communities from applying for diversions. Brookfield and Pewaukee, for example, also have radium in their water supplies.

Further muddying the proposal is the deep political divide between Milwaukee County, dominated by the majority-minority city of Milwaukee, where record unemployment besets the African American workforce – and its polar opposite, Waukesha County, conservative, affluent and racially segregated. (African Americans make up 2 percent of Waukesha County’s population.)

Waukesha officials say the intent of the diversion is to build a new water supply, and insist that an expanded service area would, in the long run, justify the $207 million cost to build pipelines and pumping stations, as demand rises in outlying areas.

Some critics, however, say an underlying aim is to fuel development in Waukesha County, shore up its suburban base, and keep it economically exclusive and politically conservative.

Political comparisons can be made to the Detroit metro area, where race and class has had an impact on water supply systems and costs, says Nicholas Schroeck, director of the Transnational Environmental Law Clinic at Wayne State University.

“Where I sit here in Detroit, we have a very similar history,” he says. “The Detroit wastewater and sewerage district grew to be this very massive water supply and wastewater treatment system that went all the way up to Flint, Michigan, and all the way over to Ann Arbor. The city of Detroit had agreed over the years to expand water to all these customer communities, which all are predominantly white, affluent communities, and the city of Detroit is a majority-minority city with a lot of very poor residents. Over time that led to all sorts of conflicts.”

Disputes arose about how Detroit set water rates, and allegations of partisanship and malfeasance were made. “That led ultimately to the situation in Flint, where now we have this water crisis,” Schroeck says, “because Flint and Genesee County wanted to get off the city water system and create its own water supply, getting water from Lake Huron. But what precipitated that was this mistrust and lack of regional policymaking for water in Michigan. With so much money involved, right or wrong, people will often use water, which we all need, as a political cudgel to try and get what they want.”

As the affluent suburbs of Detroit got on the city’s water system, urban sprawl erupted. “We’ve had crazy growth in suburban communities, and that led to the depopulation of the city of Detroit,” says Schroeck. “A lot of that sounds like what’s happened in the greater Milwaukee area.”

Returning an equal amount of water to the basin is mandated by the compact. Yet, say opponents, exceptions like the Waukesha application could lead the compact down a slippery slope.

“If an application that fails to address the requirements of the compact in so many ways is approved, that to me would amount to a precedent that essentially all straddling counties around the Great Lakes are sort of automatically approved for full development,” says Dennis Grzezinski, an environmental attorney in Milwaukee. “I’m not sure the compact means much if that’s the case.”

Kurt Chandler, the past editor of Milwaukee Magazine, is a former newspaper reporter, magazine writer, and the author of several books. He lives in Wauwatosa.

Kurt: it is so good to see your by-line again. After reading your article I started pondering the opening scene i

Space Odyssey 2001..remember those hairy chaps gathered around “their” watering hole, protecting themselves against thirsty invaders? Have we come full circle?

Thanks for the article. I continue to enjoy reading about this issue: a conservative region like Waukesha whining for a handout after squandering their natural resource. Are the other Waukesha County resources like Pine Lake, Pewaukee Lake, Okauchee Lake, Oconomowoc Lake tainted? I haven’t read that, but use by those communities hasn’t been halted.

And the Arizona scenario referenced in the article? Another case of conservative entitlement communities leaning on others for natural resources that don’t belong there. Let’s end this handout mentality.

@Gary

Remember, this is the *City* of Waukesha, not the county. The city has zero control over neighboring municipalities. The reduced area in essence solidifies the city’s boundaries by way of water service area (other than the town islands already encompassed in the city).

What a lot of folks forget when they look at the service area, is the state sets the service areas, so when the request was submitted, the city was looking at that service area as part of the long term plan, even if the city doesn’t serve it now. The state DNR would likely have kicked it right back to the city during their review (before it had gone to the Great Lakes Council) for not abiding by state law.

Now the interesting step will be how or if state law as it stands can allow the city to have these new service area boundries, or if the legislature will have to scramble to change it.

For the Racine Mayor to talk about building a pipeline to Arizone is hilarious. The compact specifically bans such a thing, so it’s a non-starter for anyone – Waukesha, Racine, Milwaukee, Detroit, etc. If he’s really concerned about it, maybe we should start asking Chicago about their river flow…

Couldn’t care less about the political/urban vs suburban fight here…my concern is for Racine. It’s already the arm pit of Wisconsin and now Waukesha wants to use it for its discharge? Of course the proponents are going to say everything will be ok. But in reality this will probably mess up the Root River’s ecosystem which 100’s of people have been trying to bring back and also make North Beach less attractive. Even if the water is clean, who mentally would want to swim in Waukesha discharge?

Casey, most cities in Wisconsin discharge their treated wastewater to rivers. Where else are they going to discharge to? So yeah, people swimming in Lake Waubesa and Lake Kegonsa south of Madison are swimming in Madison’s treated discharge water. The arguments for how the Root River’s flow will be improved by the discharge is here: http://www.waukesha-water.com/faqH7.html

Southeastern Wisconsin itself is barely within the Lake Michigan watershed.

While I have some sympathy for the folks in Waukesha, there is no way I would give them the exemption to draw from L. Michigan without some strong conditions.

The conditions might include but not be limited to passing local and state laws mandating severe water conservation measures. Base them on the pretty successful California model. Make that work for 5 years and them maybe we talk. Also, the ‘clean’ water being returned needs further scrutiny since the lake doesn’t need any more crap being spewed into it.

Just to add, I have friends who live in Las Vegas and when they moved there 13 yrs ago there was a great deal of talk among many people that the solution to their water problems would be to run a pipeline from the great lakes. I burst into laughter, but it is no joke. The southwest is in dire straits and the lack of water is a pretty pressing concern.

WaukAnon (post 3), while an Arizona water pipeline is banned by the Compact, the Compact can be changed by an act of Congress, and Arizona and the other “dry” states (including California) outvote the Great Lakes region.

If the Waukesha diversion is approved, the floodgates open to new diversion requests.

Karen, good points and both are actually implemented or will be implemented. Waukesha has had a very successful conservation campaign for several years and will continue to see improvements in that area. Second, it appears they are putting additional conditions on monitoring the water quality of the root river to make sure the water quality is acceptable.

The argument that some people make about this diversion opening up diversions to counties that don’t straddle the basin are very far fetched. Whether this passes or not, you’d need an act of congress to change the compact. Nothing changes that.

What I find interesting is that the Regional Body considering Waukesha’s application have essentially made the changes that the City of Milwaukee wanted so that the application would meet the requirements of The Compact.

Great reporting, Kurt!

Karen, I think Las Vegas has wised up since then. They reportedly revamped their whole approach and are now among the most conscientious and innovative about water conservation and recirculation in the country. They’ve redone most of their water systems or made new ones water-wise. Some other desert states have also changed in big ways.

Water challenges will continue to plague many communities around the world. People will be watching this outcome closely.

Tom D-

That the compact can be changed by an act of Congress will not be impacted by whether the Waukesha diversion is allowed or not. It is possible and always will be so.

If by “floodgates” one means that it’s possible another water-tainted community will spend years and millions in study to maybe, just maybe win approval after 12 years .. then yes. That might just happen again.