Jefferson Street Became Asphalt Showcase

Charles Pfister spent his own money to pave the street abutting his hotel in the new style.

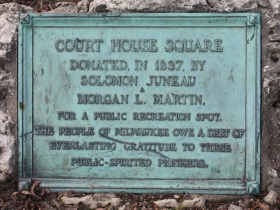

Jefferson Street was named for Thomas Jefferson, (1743-1826), the Revolutionary War patriot who drafted the Declaration of Independence and became the third President of the United States. Jefferson drew up the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which paved the way for Wisconsin to become a state in its own right, rather than an extension of an eastern state. Solomon Juneau and Morgan L. Martin named this street, which runs from E. Erie Street to E. Pleasant Street, in 1835.

Many of the early settlers to come to Milwaukee were from the eastern United States and known locally as Yankees. Some Irish were among the early settlers, and soon more Irish and many more Germans joined them. Immigrants from other nations and migrants from the southern United States followed. The children of some of those immigrants have left their mark on N. Jefferson Street.

One of those was Charles Pfister, who was born in Milwaukee in 1859, and was the son of German immigrant Guido Pfister, who came to Milwaukee in 1847 and was co-founder of the Pfister and Vogel Leather Company. In 1893 Charles built a successful luxury hotel on Jefferson Street that has retained its reputation to our time, the Pfister.

This was a decade after the Newhall House, once a first-rate hotel, but by then declining, was destroyed by fire in 1883. Officers of the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company, the owners of the site, determined that the city did not have enough premium class visitors to compete with the upscale Plankinton House hotel. Instead, they built the company’s headquarters on the Newhall House ruins at the northwest corner of Broadway and Michigan Street.

Charles Pfister thought differently, and built his new hotel just a few blocks from the Plankinton House. He also avoided one of the most contentious issues that plagued the city in the 1890s – to asphalt or not to asphalt. As the new material was introduced, property owners on virtually every street felt strongly about the issue, one way or another. Pfister bypassed the controversy by using his own money to asphalt the entire block in front of his hotel on N. Jefferson Street between Wisconsin and Mason Streets. It was the first street in the city to be paved with the new material and it was done so well that it was considered the prime example of how well asphalt could work.

In 1892, streets were named for both Pfister and Vogel as part of the development of the suburb of Cudahy. There is no longer a Pfister Avenue; it is now part of Mitchell International Airport. Vogel Avenue fared better; it was extended to the west and is now part of Milwaukee.

In 1887, an alderman proposed that Chicago Street in the Third Ward be renamed Keenan Street for Matthew Keenan. That idea died a quiet death.

William George Bruce (1865-1949), was the son of German immigrants. He was born in Milwaukee and was an avid supporter of the city. In particular, he was instrumental in the building of the Auditorium (now called the Milwaukee Theater) and its main hall was named for him. He advanced the city’s seaport interests by serving as the first president of the Harbor Commission and vice president of the St. Lawrence Seaway Council. He was an author, historian, and publisher.

Bruce is also responsible for the Immigrant Mother statue in Cathedral Square, just off N. Jefferson Street. He left $30,000 in his will to honor motherhood. The 1960 statue by Ivan Mestrovic was placed in Cathedral Square facing the doors of the church because Bruce was a devoted Catholic.

Park Street in Walker’s Point was renamed Bruce Street by ordinance in 1929. It was unusual for a street to be named for a living person during this era for fear the honoree might bring discredit to the name in the future. But Bruce brought only credit to himself and his city during his later years.

An unusual feature of the 1.5 mile long N. Jefferson Street is that four of its blocks are closed to vehicular traffic. They were vacated during the mid-to-late 1960s. The block between E. Clybourn Street and E. St. Paul Avenue includes a tunnel under the freeway for pedestrian use. The block between E. Kilbourn Avenue and E. State Street is now a Milwaukee School of Engineering mall used primarily by students. The next two blocks between E. State and E. Knapp Streets feature sidewalks in an almost park-like setting and were part of a neighborhood renewal project.

Carl Baehr, a Milwaukee native, is the author of Milwaukee Streets: The Stories Behind their Names, and articles on local history topics. He has done extensive historic research for his upcoming book, Dreams and Disasters: A History of the Irish in Milwaukee. Baehr, a professional genealogist and historical researcher, gives talks on these subjects and on researching Catholic sacramental records.

Along Jefferson Street

City Streets

-

Revised Milwaukee Streets Book Dishes the Dirt

Nov 3rd, 2025 by Michael Horne

Nov 3rd, 2025 by Michael Horne

-

The Curious History of Cathedral Square

Sep 7th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

Sep 7th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

-

Gordon Place is Rich with Milwaukee History

May 25th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

May 25th, 2021 by Carl Baehr