Teaching Poor Kids Where They Live

Learning centers in subsidized housing target low-income and black achievement gaps.

‘Home away from home’

Ien Roder-Guzman, 24, describes the learning center in the apartment complex where he lived as a “home away from home”: “They kept me grounded and kept my head focused on future stuff.”

Roder-Guzman grew up at the Packer Townhouses on Madison’s North Side and began going to the community learning center when he was 5. Despite moving around Madison and attending several schools, Roder-Guzman kept coming back to the learning center — even when he was not living in the neighborhood. He now works at the learning center three days a week.

“Just family. The family feeling, you know?” he said, explaining why he kept returning to Packer. “I came here feeling at home, pretty much.”

Roder-Guzman graduated from Madison College in December with a two-year liberal arts degree that will help him transfer to a University of Wisconsin System school. He is also considering joining the military. He said the learning center became a “main support system” for him while in school.

“You keep coming back here, and it’s like they’re going to help you no matter what,” Roder-Guzman said.

Ien Roder-Guzman, 24, hugs his dad Scott Roder after Madison College’s graduation ceremony in December. Photo by Coburn Dukehart of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

Anecdotal evidence for learning centers

Data on Porco’s learning centers are limited. But what is available indicates students who are participating in the on-site educational programs are succeeding, said Charles Taylor, an education professor at Madison’s Edgewood College.

Taylor gathered data from students in Porco’s housing units and compared them to Madison and Milwaukee students overall. Although the sample size of 68 students was small, Taylor found that students living in the stable, low-income housing complexes exceeded their peers in each city.

As of October, Taylor and Margaret Porco, an assistant to her father Carmen, estimated the grade-point average of current and graduated scholars in the Madison properties who participated in the learning centers averaged 3.2 and scholars in Milwaukee averaged 3.3 on a scale of 4. Figures for comparable students were not available, but Taylor said he is convinced the learning centers are making a difference.

“This is something that I believe is worth celebrating and duplicating,” Taylor said.

The adjoined Greentree and Teutonia apartment complexes are two of six low-income properties run by Carmen Porco, an executive in Housing Ministries of American Baptists, across Milwaukee and Madison. The learning center on site provides educational opportunities, social services and even jobs for some residents. Photo by Abigail Becker of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

Taylor and Margaret Porco also found students living in the housing complexes graduate at higher rates than the district average for all students. From 2010-14, 97 percent of students in the study at the Madison properties graduated, and 100 percent of students in the study at the Milwaukee properties graduated, Taylor found. The four-year graduation rate for all students in the Madison district is 79 percent and Milwaukee’s is 61 percent.

Taylor said he did not compare graduation rates by race or ethnicity between schools and housing units. However, he said it was “clear from every source” that black students living in the complexes graduated at higher rates than their peers in Madison and Milwaukee.

The same trend was true for Latino and Hmong students, Taylor said.

Eric Grodsky, an education researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said Porco’s work on Madison’s North Side “sounds amazing,” but without a more rigorous study of the program, it is hard to know the extent of the centers’ effectiveness.

“With a strong evaluation I think their work could benefit hundreds if not thousands of kids,” Grodsky said. “Without that evaluation, it’s a lot harder to get other entities to commit the sorts of resources necessary to do what they have done.”

Scholarships key to college success

Since 2006, the properties in Madison and Milwaukee have given out about $668,000 in scholarship money to more than 115 individuals. Residents pursuing undergraduate or master’s degrees said the scholarship and rent-assisted housing were critical to completing their degrees.

Wanda Melton, 33, who has a 12-year-old daughter, is a school counselor at Northwest Catholic School in Milwaukee. She completed her bachelor’s degree in psychology at Upper Iowa University in 2010 and earned her master’s degree in school counseling at Mount Mary University in 2014 while she was a resident of Greentree-Teutonia.

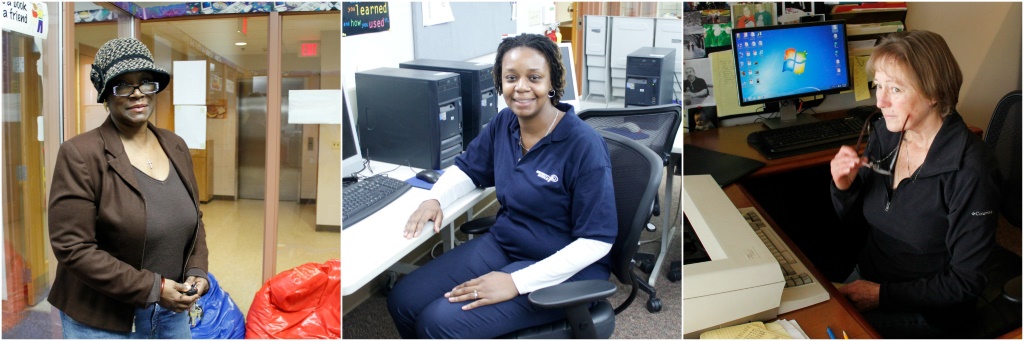

From left, Greentree-Teutonia program director Vicki Davidson, standing in the reading room, describes herself as a “beast for education. Former Greentree-Teutonia resident Wanda Melton, a school counselor at Northwest Catholic School in Milwaukee, says the stabilized rent at the apartment complex helped her complete her college degree. Jean Knuth, manager of Greentree-Teutonia, said before the learning center was built on site, the apartment complex was “just a housing business.” Photos by Abigail Becker of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

While she was completing her counseling degree, Melton said she was required to complete an internship and had to take an unpaid leave of absence from her job. The scholarship and the rental assistance helped her pay the bills.

“I definitely was able to lean on the scholarships,” Melton said.

Jean Knuth, Greentree-Teutonia’s housing manager, said the learning center has turned the complex into a community that meets many needs. There is child care, tutoring for students and a computer lab with resources for job searching and resume writing.

“We can’t fix everybody and we can’t fix all of their children, but we can do something,” Greentree-Teutonia program director Vicki Davidson said. “All they have to do is let us know what they need.”

Children Left Behind

-

Study Shows Poverty’s Impact on Kids

Jul 9th, 2016 by Abigail Becker

Jul 9th, 2016 by Abigail Becker

-

Wisconsin Going Backwards on Achievement Gap

Dec 21st, 2015 by Abigail Becker

Dec 21st, 2015 by Abigail Becker

-

State Has Worst Black-White Learning Gap

Dec 19th, 2015 by Abigail Becker

Dec 19th, 2015 by Abigail Becker

Wow, fabulous! This system is achieving real results for our nations children. The Housing Ministries of American Baptist in Wisconsin needs a more visible campaign for fund raising.