Does the Estabrook Dam Cause Flooding?

Supporters of removing dam say it would reduce flooding, but their data is suspect.

Existing Flood Mitigation Efforts and Plans for Areas Subject to Flooding

As previously noted, a study completed by SEWRPC in 2006-10 evaluated alternative flood land management plans for the main stem of the Milwaukee River in the 13.2-mile-long reach from the Milwaukee-Ozaukee county line downstream to the upstream limit of the Milwaukee Harbor estuary at the location of the former North Avenue dam. The analysis by SEWRPC was primarily intended to evaluate alternative plans to mitigate flood damages at 393 buildings located within the 100-year floodplain of the Milwaukee River in the Cities of Glendale and Milwaukee and the Villages of Brown Deer and River Hills. Although perhaps 75 percent of structures that were the focus for the SEWRPC study are located within the section of the Milwaukee River that is part of the Estabrook Dam impoundment, there is no mention of the dam in the study, or its potential contributing role to flooding. Presumably, either the dam was viewed at that time as being irrelevant to overall flood mitigation planning for this portion of the Milwaukee River, or this was an oversight in the planning effort.

The SEWRPC study evaluated three general alternatives for mitigating flooding in this area: (1) acquisition, demolition, and removal of all homes and buildings from the flood plain (capital cost: $107.6 million); (2) selective acquisition and demolition of buildings and flood proofing (capital cost: $38.2 million); and (3) construction of a levee in combination with selective acquisition and demolition of buildings and flood proofing (capital cost: $61.2 million). Glendale officials objected strenuously to Alternative 1, which would have destroyed by their estimate about 8 percent of the city’s single family residences and 5 percent of its total tax levy. Alternative 2 was recommended, with 98.7 percent of project costs to occur within Glendale. Components of the plan included acquisition and demolition of 70 structures (at an estimated total cost of $19.5 million and average cost of $278,500 per structure), raising the elevation of 176 structures at least two feet above the level of the 100-year flood (at a total cost of $15.8 million and average cost of $89,800 per structure), and flood proofing of the remaining 138 structures at an average cost of $17,000 per structure.

Although Glendale concurred with the recommendation (including removal of 19 of the most flood-prone homes within the Sunny Point Peninsula area), the city’s support was conditional on the program being voluntary, fully funded, and giving greater consideration to flood proofing or raising the elevation of structures as an alternative to demolition in areas outside of the Sunny Point Peninsula. I was unable to confirm the current status of the flood mitigation program, other than that some homes within the floodplain have been purchased and others raised above the modeled flood elevations. Although details do not appear to be readily available, a key takeaway appears to be that a flood mitigation program is already in progress to address all homes and businesses within the vicinity of the impoundment that are currently mapped as being subject to a 1 percent probability of flooding.

The relative lack of reported damage from a 200-year flood event is notable indeed given that at least 71 structures in Glendale are modeled to be within the 10 percent probability of flooding — at risk of damage from a far smaller 10-year flood event. Based on the analysis performed by SEWRPC in 2014 for the Estabrook Dam, flood levels modeled for a 100-year event are from 2.90 to 4.95 feet higher than those for a 10-year event for the section of the River between Silver Spring Dr. and Bender Road. Thus the 71 structures within the 10-year flood area should have been inundated by at least 3 to 5 feet of water during the 200-year flood event of 1997.

Based on the very limited damage reported from the 1997 flood, there appears to a discrepancy between actual flood levels during a major flood and those predicted by the SEWRPC model, which leads to additional questions regarding its ability to accurately predict the impacts if any from the Estabrook Dam.

In conclusion, studies performed by SEWRPC suggest that in an area north of Silver Spring Dr. and south of Bender Rd., removal of the Estabrook Dam would result in reductions of between 0.32 to 0.03 feet in the modeled 100-year flood elevations. If the modeling is correct, the dam’s removal results could result in an undetermined (although likely small percentage) of homes being removed from the official 100-year flood boundaries (and thereby relieved of associated flood insurance requirements). My guess is that fewer than 10 homes might be affected. The lack of specifics on the number of homes impacted appears to have led to significant misunderstanding by some property owners as well as public officials regarding the impact of dam removal on reducing flood levels.

Furthermore, the modeled flood impacts may be exaggerated versus the actual flood impacts, given a 200-year frequency flood event in 1997 reportedly resulting in $405,000 in combined flood damages/expenses in Glendale – an amount that is only about 3 percent of the damages predicted in the 2010 SEWRPC study for a lesser 100-year flood event. Therefore, the actual flood reduction benefits from removal of the dam could be substantially lower than the already limited impacts predicted by modeling.

Finally, the impact of dam removal on current plans by MMSD to address all structures in this area subject to a 100-year flood has also not been detailed. Presumably, the small group of homeowners that might be freed from federal flood insurance requirements as a consequence of removal of the dam might see the same or better result from the MMSD project, including a higher level of protection from an actual flood event, as well as localized flooding unrelated to the Milwaukee River or Lincoln Creek.

The flood of July 22, 2010 is worth reviewing in this context. Thousands of homes in the Milwaukee area were flooded on this date, including hundreds of homes in the area surrounding Lincoln Creek. But the flooding in neighborhoods bordering Lincoln Creek was reportedly not caused by overflow of the creek banks but instead by localized flooding of streets. Residents who were freed from flood insurance requirements as a result of the $110 million Lincoln Creek flood mitigation project completed only eight years earlier suffered devastating losses from flooding, with some homes a total loss and subject to demolition. Glendale experienced significant flood damage, but most appears to have been associated not with overflow of the Milwaukee River, but with localized flooding such as that which resulted in a $12.9 M property insurance claim by Nicolet High School.

The recent hydraulic modeling performed in support of the EA for the Estabrook Dam presented an opportunity for an important community dialogue to take place regarding flood issues in Glendale, including the assumptions and limitations associated with the hydraulic modeling, the flood risks posed by the Milwaukee River versus flooding of streets or from sewer backups, and the status of flood mitigation efforts in progress. Unfortunately, this opportunity has not been taken advantage of, and the debate regarding the dam appears to have decreased rather than increased public understanding regarding the flood issues in this area.

Confusion related to models is reportedly a common issue in dam removal/repair decisions, as noted by William Steele during his keynote address at The Heinz Center’s Dam Removal Research Workshop October 23–24, 2002, as published in Dam Removal Research: Study and Prospects:

“The major challenge for the scientific community is to protect against the misuse of models by its members or by decision makers. Transparency and effective communication about the assumptions and uncertainties that may be embedded in the models are both difficult and important. Often, the language of modeling is extremely obscure to the lay public, and thus caveats that seem clear to the scientific community are completely lost in the din of public debate. Modeling becomes a tool of misinformation as much as a tool of useful information.”

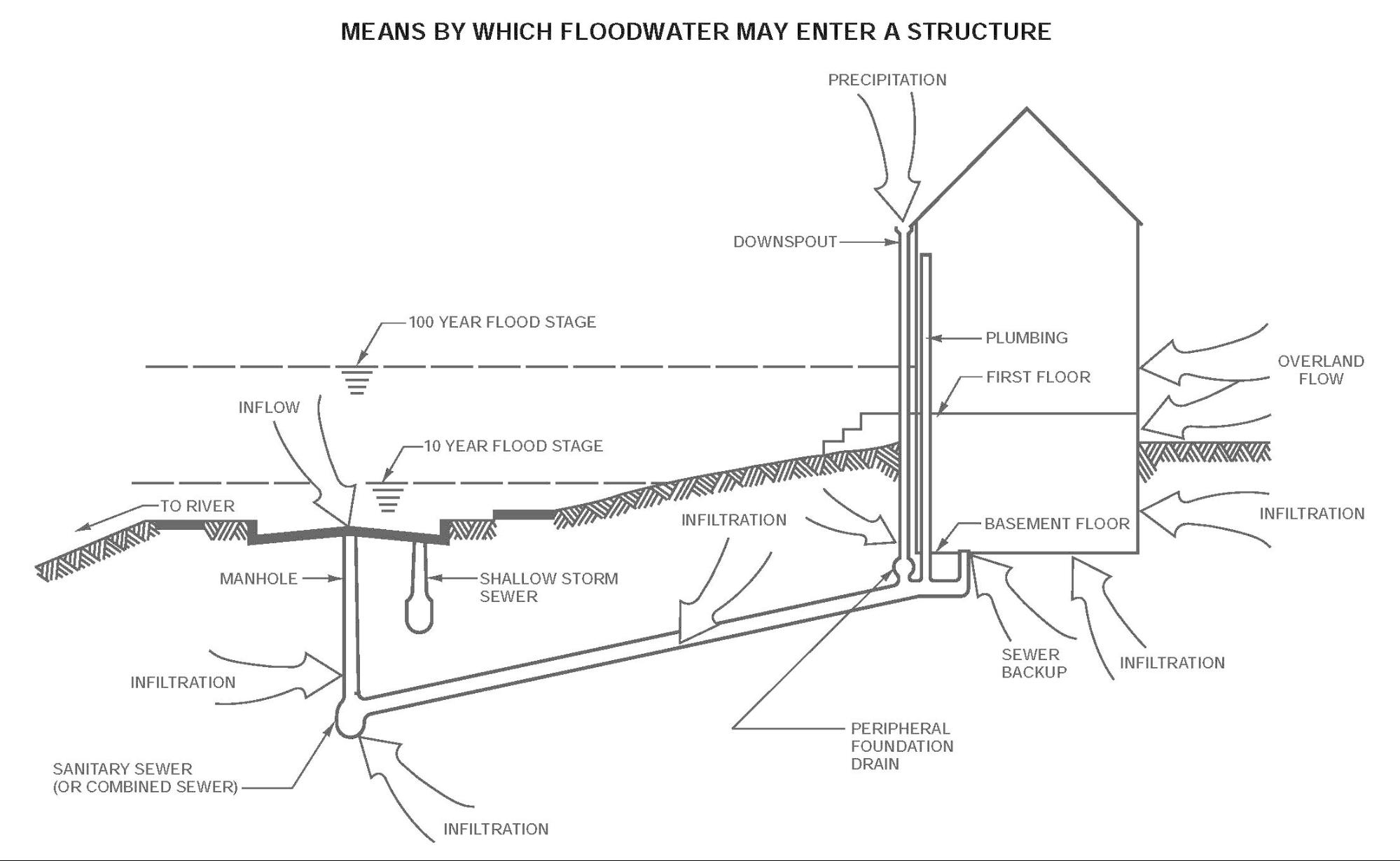

Drawing from SEWRPC (2010) illustrating the many means by which floodwaters can enter homes, including overflow of rivers, overland flow, infiltration from elevated groundwater levels, and sewer backups.

As the diagram above demonstrates, flooding of homes can occur from many causes. It’s entirely possible the removal of the Estrabrook Dam will have little impact on flooding. There is still time for the community to fully discuss this issue and choose the best and most cost-effective way to prevent flooding.

Coming next: Environmental and environmental justice issues raised by the dam’s removal.

David Holmes is an environmental scientist and urban revitalization consultant pursuing a Doctorate in Freshwater Sciences at the UW-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Science.

Article Continues - Pages: 1 2

A Freshwater Controversy

-

The Path Forward for Estabrook Dam

Feb 10th, 2016 by David Holmes

Feb 10th, 2016 by David Holmes

-

Estabrook Dam’s Environmental Impact

![Photograph of fish passing through the fish passage at the Mequon-Thiensville Dam. As of June 2015, a total of 35-species of fish have been recorded by a “fishcam” in the act of swimming past the dam [http://www.co.ozaukee.wi.us/1248/Fishway-Camera]).](https://urbanmilwaukee.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/image03-185x122.jpg) Jan 17th, 2016 by David Holmes

Jan 17th, 2016 by David Holmes

-

Repairing Estabrook Dam Will Cost Less

Dec 23rd, 2015 by David Holmes

Dec 23rd, 2015 by David Holmes

Why the controversy since the dam is always open anyway? The doors are never in the down/closed position so why not save all the money and just leave it alone?

Richard, that’s a good point… let it crumble into a new natural landform and it’ll be the cheapest by far. Probably a little artistic too.

We are grateful for the work of David Holmes and people like him at Urban Milwaukee. While other news outlets were reluctant for financial reasons, or afraid, too stupid or too lazy to check the facts and provide the truth, David Holmes and Urban Milwaukee are doing the hard and courageous thing. They are bringing us the whole story, both sides of it.

If the Estabrook Dam is removed, it would be the single most costly mistake Milwaukee County would make this decade. I believe the information in these David Holmes articles validate the messages I and my colleagues in the Milwaukee River Preservation Association have been saying for years. Milwaukee County Parks, at the direction of the county executive have been providing misinformation for the purpose of swaying public opinion toward dam removal. I believe they are determined to take the only boatable lake in the county away from the people of Milwaukee County. These decisions were made based on intentionally exaggerated figures. Plans were quietly made and implementation begun as thoroughly as possible without public input. Parks, DNR, and BLM steadfastly denied any facts that contradicted their goal of dam removal. Explanations were made so complicated and contradictory that most people were confused. The BLM even claimed ownership of part of the dam until irrefutable evidence proved them wrong and they backed-off in embarrassment. When public opinion was required by law, the Parks Department used every available technicality to make their reports appear as if the public supported dam removal, regardless of the overwhelming majority of responses supporting dam repair. When that didn’t work, Parks ran a second online survey and when that didn’t agree with their agenda, tried the same cherry picking tactics when reporting to the county parks committee. The Parks Department and DNR bureaucrats must already know that misinformation and crooked political maneuvers would be their only means to achieve dam removal because water law, economics and water science do not support their claims. Until David Holmes checked the facts, even he seemed convinced by the media and the “environmental community” that this dam was bad for the environment. To their credit, Milwaukee County Board of Supervisors lead by Chairman Lipscomb, were familiar with this kind of media and special interest pressure and supported their constituents. The board consistently approved dam repair. They budgeted and funded the necessary money in 2010, but bureaucrats who serve at the pleasure of the county executive hoped for a reversal and have managed to delay dam repair for more than 6 years since then. Bureaucrats continued to find technicalities for delay or reasons to make the county board vote over and over again.

Repair opponents lead by the Riverkeeper kept pressure on elected officials to remove the dam. Milwaukee and Shorewood passed resolutions supporting dam removal because of Riverkeeper pressure without even checking facts or opposing viewpoints with dam repair proponents. Even though most of the lake is in Glendale, City of Glendale mayor and common council were instructed by their legal counsel to not get involved. Glendale’s aldermen as well as the city attorney told me that municipalities were afraid of being drawn into costly lawsuits with the Riverkeeper and could not get involved. I believe donations to the Riverkeeper fund lawsuits against our county that cost tax dollars and support a bully with a bad agenda.

If Estabrook Dam is removed, it will require another Flood Insurance Study. That would include a new hydraulic study and elevation mapping for the portion of the Milwaukee River Watershed that falls inside Milwaukee County. This is an expensive process and most communities can only afford to pay for a flood study every 10 years or more. The National Flood Insurance program (FEMA) will not remove any homeowner from a Flood Hazard Map until there is data that supports flood risk from a 100 year event has been reduced for a homeowner. And only FEMA has the authority to accept or reject requests for map revision.

As David Holmes has suggested only a few homes may be removed from a flood map. But a new expensive Flood Study would be required by FEMA and no guarantee any homes would be removed from a flood hazard map. This information can be found in the FEMA website under Letter of Map Revision (LOMR).

I was previously swayed by various reports that dam removal made sense. I am glad that David Holmes has provided rigorous research and reporting that calls for reconsidering that approach.

Unfortunately, we live in a time where everything is reduced to sound bites and opinions or information the length of tweets. And media stories are often just composites of a few facts, some of which are merely recycled over and over.

Now that more data is out there I hope this issue will be analyzed in even greater depth by those with expertise. I fear it has become more of a political issue than a scientific or even economic one.

I know there are cases where removal of dams has made sense and been beneficial. However, the articles in this series question whether that is the case with Estabrook. I wonder if David Holmes might address that in a future article (or perhaps he has in this series and I missed it). That type of contrast might help to further clarify what perhaps are unique or at least exceptional aspects of this particular case.

The whole premise of this article is ridiculous. Let us think about it for a second. Why would the Estabrook dam prevent flooding up-stream of its location?

It wouldn’t!

A dam evens out the flow of water on the downstream side of the river. If the author of this article was really interested in preventing flooding in Glendale, wouldn’t a dam further up river that limits the water flowing down, wouldn’t that be the “solution” for dam happy people?

The Estabrook dam would limit the water from leaving, causing flooding upstream while saving areas downstream from flooding. This may have been necessary years ago but the river bank downstream of the Estabrook dam is now impervious to flooding until it reaches Lake Michigan.

So Tim, to sum up what you’re saying: You didn’t read the article.

This is a great series of articles.

One option that was dismissed in a single sentence in the last article was replacing the gates with a rock ramp (effectively a fish passage). This is exactly how the Theinsville dam is built.

As mentioned in the comments above the gates are permanently open, so a rock ramp would hardly change any flow at all.

I have to say until reading these articles I thought removing the dam meant removing the gates – big difference!

David I would really appreciate your opinions on replacing the gates with a fish passage, or rock ramp.

Thanks

AG, if you want to have a new dam built, why don’t you pay for it?

Just as tree roots can enter water lines and slow the flow and back up the delivery of water, the shallow areas of the river above the dam that have been exposed are overgrown with Cottonwood trees, Dogwood, Willow, Purple loosestrife and more, which will noticeably slow flood waters, back them up and cause the river to overflow it’s banks above the clogging constrictions. Just that simple. When the Estabrook dam was in operation it prevented those trees and thick shrubs from gaining any foothold on the river bed. Flood waters use to race by the house. Now the river is pulled on and slowed by tens of thousands of branches.

Tim, don’t be mad at me because you didn’t read the article…

But as a taxpayer, I would be paying to replace it. I’m ok with that.