Has Wisconsin Become a Can’t Do State?

State’s still lagging economy points to problems with political leadership.

The Wisconsin economy continues to lag the US and most other Midwest states. Increasingly, this performance appears to relate to a state culture that worries far more about costs than on seizing opportunities.

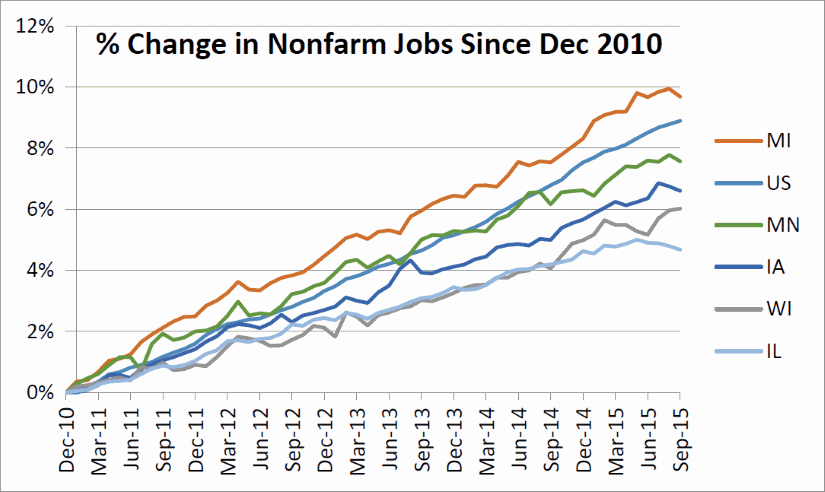

The graph below shows the percentage change in nonfarm jobs since December of 2010. Of the states bordering Wisconsin only Illinois—where political gridlock blocks any solution to the nation’s most badly-funded pension fund—has done worse.

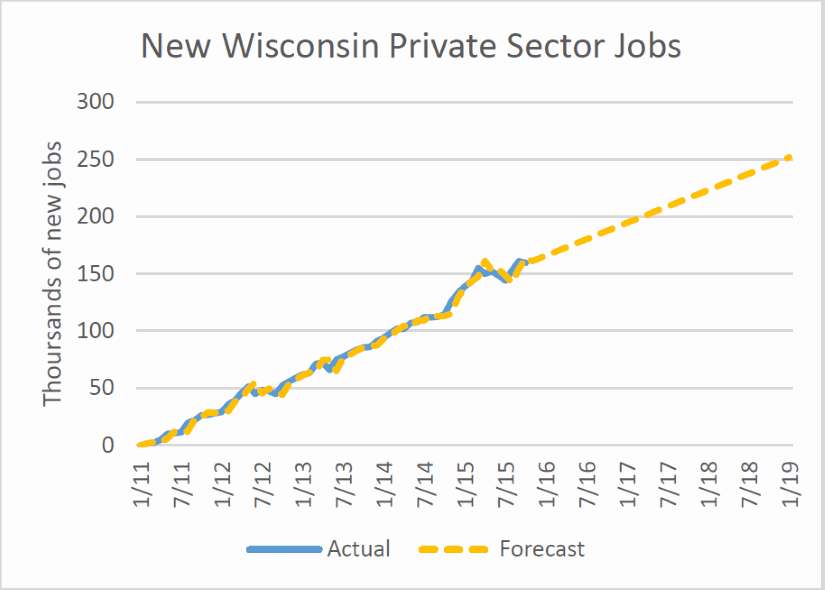

Another measure is the growth of private-sector jobs. The graph below shows the actual growth of private-sector jobs (in thousands) since December of 2010. It also includes a forecast (using the Holt method) to the beginning of 2019.

As a candidate in 2010, Scott Walker famously promised that, if he were elected, Wisconsin would add 250,000 new private-sector jobs by the end of his first term. Instead it appears that promise will require his full two terms to fulfill.

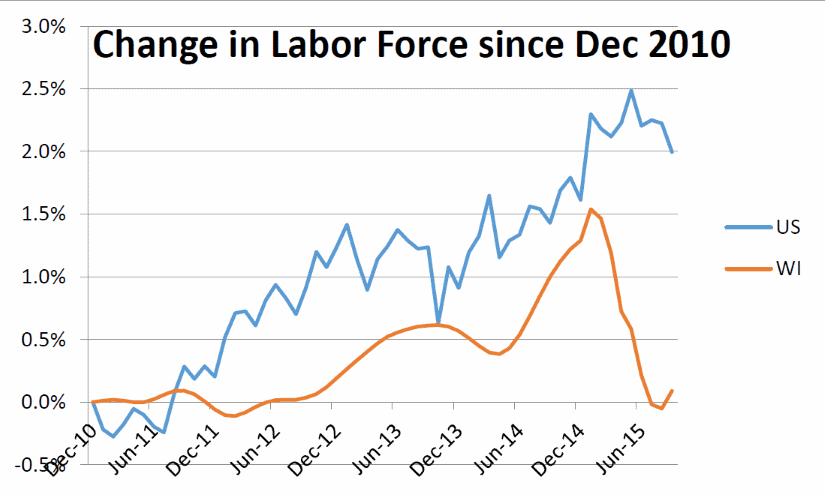

A shrinking labor force is also of concern. As part of its American Community Survey, the Census Bureau asks a sample of households whether they are currently employed or looking for work. If they are, the bureau counts them as part of the work force. To calculate the unemployment rate, it divides those looking for work by the work force.

The job numbers are calculated from a completely different survey in which a sample of employers is asked about the number of employees. While over time the two measures usually tell the same story—an improving economy adds jobs and drives down unemployment—on a monthly basis they often diverge simply due to sampling error. Usually a declining unemployment rate is good news.

Sometimes, however, it can reflect bad news: that the labor force is shrinking faster than employment. Recent data indicate that the Wisconsin labor force has taken a sharp dive. As a result the labor force is the same size it was in 2010, as shown below. The recent declines in the unemployment rate are largely due not to more jobs, but to a the shrinking labor force.

There are many possible explanations for this, including the retirement of baby boomers, more people staying home to care for their families, or more students. Generally, however, one would expect the labor force to grow along with a growing economy as “discouraged workers” reenter the job market. But that is not happening in Wisconsin. One possible explanation is that job hunters have decided the grass is greener in other states.

At any point in time, various reasons may account for why one state booms while another stagnates. Historically booms and busts have related to raw materials or transportation hubs. Increasingly, however, they have more to do with a region’s culture than geography.

Last summer our family spent a week in the eastern Kentucky coal country. The attraction was Appalachian music, not coal, but remnants of the coal business were all around: abandoned mines, abandoned coal conveyers, abandoned train tracks, even the hotel we stayed in was converted from a school for the children of coal miners. No coal was being mined in our valley—I was told there was none left—but nostalgia for coal and the well-paying, if dangerous, jobs it brought was all around.

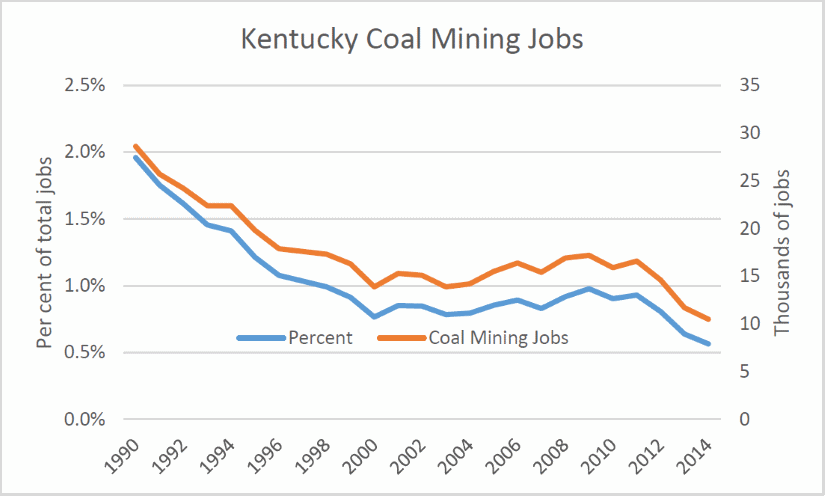

A news item reported that both candidates for governor had visited the coal industry association to pledge their fealty to the industry’s revival. “Coal Keeps the Lights On,” was the popular bumper sticker. And yet coal has steadily shrunk to become a tiny part of the Kentucky economy. As the next graph shows, coal employment in Kentucky since 1990 has dropped from 30,000 to about 10,000 jobs — now well less than 1 percent of the state’s jobs.

Much of the drop had nothing to do with the hated “war on coal” but came about because of new technology, including huge machines made in Milwaukee, and a shift from underground mines to strip mining and mountain top removal. More recently, the boom in gas from fracking reduced demand for coal. However, the obsession with coal makes it very hard for Kentuckians to think about what could replace it.

While the fixation with protecting coal may be short-sighted, at least in Kentucky it is understandable. Consider the reaction in Wisconsin to the EPA’s Clean Power Plan, which is expected to result in a major shift in electricity production from coal to other sources. Although we in Wisconsin mine no coal, the fierce opposition to the EPA’s plan in Wisconsin would make one think coal had been discovered under Waukesha.

Here is the MacIver Institute:

According to a joint report by the MacIver Institute and The Beacon Hill Institute at Suffolk University, the original Clean Power Plan proposal would cost Wisconsin $920 million in 2030, increased electricity prices by 19 percent and lowered disposable income in the state by nearly $2 billion. Now that the finalized rule requires a larger percentage of carbon emission reductions, these figures could be even higher for the Badger State.

Governor Walker sent a letter to the EPA quoting a Wisconsin Public Service Commission estimate that EPA’s preliminary plan would cost Wisconsin $3.3 to $13.4 billion. A joint letter went out signed by the Wisconsin DNR, the PSC, and the state Attorney General quoting the same figures. Finally, Wisconsin joined other states—including Kentucky–in Case 15-1363 in DC Circuit Court challenging the EPA’s right to issue the plan.

As I’ve written previously, even if past predictions of conservative opponents to the EPA proposal were taken at face value, the impact amounts to about one-third of one percent of the total U.S. economy and about two months of job growth for Wisconsin and the Midwest.

Wisconsin is only a small part of the total spending, and thus the total employment generated. Where will those jobs be? Will they be in China, or California? Certainly they will not be in Kentucky given the public attitudes there. And how likely is it that solar, wind, or other companies whose strategy is countering global warming will try to expand operations in Wisconsin?

This suggests a possible explanation for why Wisconsin has underperformed. We have become a “can’t do” state. We have become fixated on costs, including sunk costs, not opportunity. A number of recent actions—including turning down the federal rail grant, attempts to sabotage the Milwaukee street car, and refusing to expand Medicaid—suggest that Wisconsin should be numbered among the can’t do states, obsessed with cost rather than looking for opportunity.

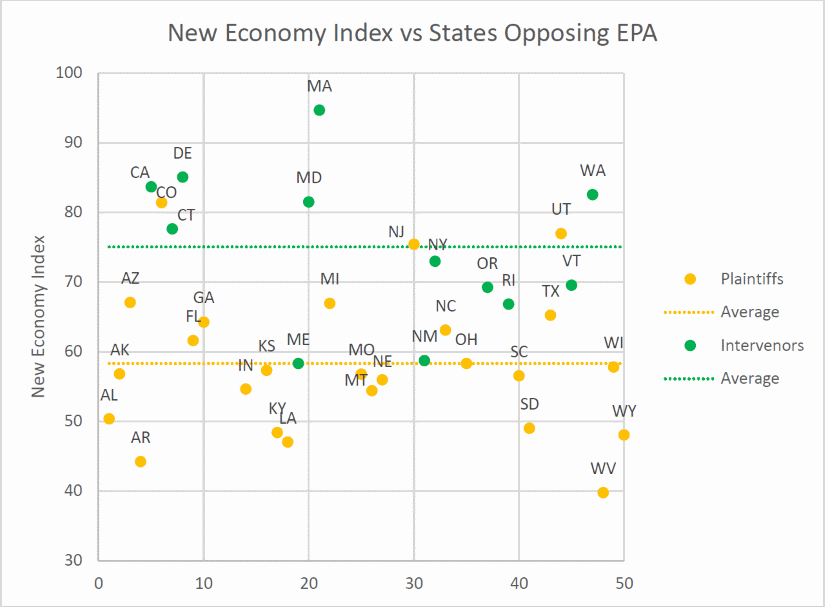

A quick and dirty way to identify the other states focusing on cost rather than opportunity is offered by the lawsuit challenging the Clean Power Plan. Those joining the lawsuit are shown in yellow in the next graph. The states intervening to oppose to the lawsuit against the initial draft of the regulations are shown in green.

The vertical scale shows each state’s rating on the New Economy Index put out by the International Technology & Information Foundation. The index “uses 25 indicators to measure the extent to which state economies are knowledge-based, globalized, entrepreneurial, IT-driven and innovation-based.”

There is a definite correlation between whether a state joined or opposed the lawsuit and how it rates on the New Economy Index (for the statistically inclined the p-value is 0.00026). None of the states opposing the lawsuit has a New Economy score below the average score (shown as a dotted orange line) for the plaintiff states. Conversely, only three states joining the lawsuit exceed the average New Economy score for states supporting the EPA rule. The highest scoring of these—Colorado—is an interesting case. Under that state’s law, its attorney general was able to join the lawsuit even though it was opposed by the governor, whose comments stand in sharp contrast to what comes out of Wisconsin:

We do not support this lawsuit…Clean air and protecting public health should be everyone’s top priority. …This lawsuit will create uncertainty for the state and undermine stakeholders’ ability to plan for and invest in cost-effective compliance strategies…We believe that Colorado can achieve the clean air goals set by the EPA, at little or no increased cost to our residents.

I suspect that the two groups of states — those joining and opposing the lawsuits — have very different cultures. For example, those joining the suit are likely to worry more about costs than about seizing opportunity. Those states also find it much easier to dismiss the findings of science, in this case climate science. And those states are more likely to be left behind as others find alternative energy solutions.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Your last paragraph nails it, Bruce. Wisconsin’s economic policy is run by old-money oligarchs who want nothing more than to protect their position, and grab more market share and profit at the expense of everybody else. Innovation or attracting talented innovaTORS is not part of that equation. Just lobbying and more grabs from money and power.

Gee, you wonder why this state is doing so badly for job growth in the Age of Fitzwalkerstan?

If a person is worried about how well the economy is going to be in the next 100 years or so, then working to reduce global warming should be high on their to-do list. Our economy is already feeling the impact of climate change and it’s only going to get worse. by the year, 2100, it will reduce the GDP by about 25%! Those in less moderate climates will be more greatly effected. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-10-21/climate-change-slams-global-economy-in-new-study-from-stanford-and-berkeley

err… affected. effect / affect. whatever.

Possible new state slogan: “Wisconsin: We’re still better than Illinois.” Also, a question. When we talk about “new jobs created” by Gov. Walker or anyone else, do we subtract jobs lost (e.g., Oscar Meyer)?

Thanks, Data Wonk, for keeping it real.

Mark,

Yes. The change in jobs is a net figure, so that if 1000 jobs were added and 1000 lost, there would be no change.