Government Policies Tough on Working Poor

Many work for fast food chains and are hurt by Badger Care changes.

With Labor Day approaching, it’s a good time to reflect on all the families in Wisconsin who are struggling to work their way out of poverty. Unfortunately, many of them are held back by public policy choices made at the state and federal level, as well as changes in the workplace. These obstacles include a stagnant minimum wage, inadequate federal rules on eligibility for overtime, barriers to accessing child care and affordable health care, and the growing use of on-call scheduling of workers.

When we think of low-wage workers, particularly those making the minimum wage, we often think of teenagers working in the fast-food industry. However, data on earnings for low-income parents paints a very different picture, as does recently updated data on the employment of people participating in BadgerCare.

Before I turn to the statistics, let’s consider the case of a young single mother who has one child and is working in a fast food restaurant where she makes $8 per hour and about $16,600 per year. While she struggles to support her family on that income, which is slightly above the poverty level for a family of two, she faces the following hurdles:

- Like many other low-wage workers, she increasingly finds that her work hours are changed on short notice, making it nearly impossible for her to find quality child care for her young child.

- In April 2014, state policy changes made her ineligible for BadgerCare, so she must now spend 2% of her income or about $28 per month for the premiums for a Marketplace insurance plan, which has substantially higher copays and deductibles than BadgerCare.

- Governor Walker’s proposal to repeal and replace Affordable Care Act would go even further, by sharply reducing the subsidies for her Marketplace plan, resulting in much higher premiums, copays and deductibles.

- If she takes a promotion to a job with a salary equivalent to $11.50 per hour, she would make too much to be assured of receiving overtime pay (unless or until the federal Dept. of Labor approves a proposed rule change).

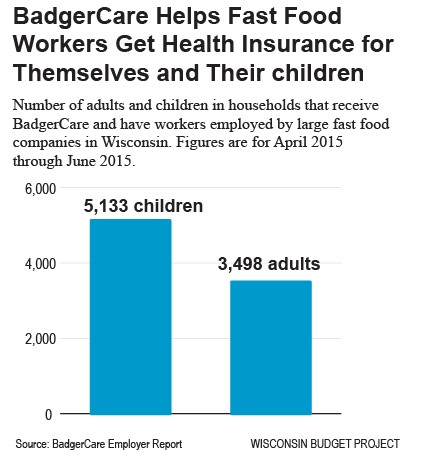

If you have the impression that few parents work in the fast food industry, take a look a recently released set of data about BadgerCare participation from the Wisconsin Dept. of Health Services. That database provides information regarding the 50 employers who have the largest number of Wisconsinites enrolled in BadgerCare. During the second quarter of 2015, there were 8 fast food chains (as well as two other restaurant chains) on that list. Among those fast food chains, there were nearly 3,900 households who utilized BadgerCare – accounting for 8,631 BadgerCare participants: 3,498 adults and 5,133 children.

Although the DHS dataset leaves many holes in our understanding of those fast food workers and their families, a recent report from the Economic Policy Institute sheds a lot of light on the low-wage workforce. They analyzed national and state-level data to determine who would benefit by gradually raising the minimum wage to $12 per hour in 2020, and they found the following:

- The average age of the workers who would get a raise is 36 years old, and more of the affected workers are age 55 or older (15.3%) than are teens (10.7%).

- Almost 56% of the affected workers are women.

- More than one-third of black and Hispanic workers would receive a raise, compared to one-fourth of all workers.

- In Wisconsin, an estimated 23.8% of workers would get a raise, including the families of one-fifth of Wisconsin children.

Nationally and in Wisconsin, the middle class has been shrinking – thanks in part to policy choices that make it difficult for hard-working families to climb the economic ladder. We could begin to reverse that by boosting the minimum wage, undoing at least a portion of the cuts to BadgerCare eligibility for parents, and making more workers eligible for overtime pay. Only by helping low-wage workers and broadening the middle class can we expect to strengthen Wisconsin’s economy.