Ruling Could Pollute Drinking Water State-Wide

EPA opens door to reuse of coal ash, despite evidence it's contaminating wells in Wisconsin.

Frank Michna’s dog, Sophie, refuses to drink water from the taps in his Caledonia home. Michna said the dog sniffs the tap water and then drinks instead from a bowl filled with bottled water. A study by the environmental advocacy group, Clean Wisconsin, linked pollution in Michna’s and hundreds of other wells to buried coal ash from the nearby We Energies Oak Creek Power Plant. Photo by Cole Monka / Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

By: Ron Seely, Kate Golden, Rachael Lallensack, Cole Monka and Daniel McKay

It’s not a good sign when even the dogs won’t drink your tap water.

“They sniff it and then drink the bottled water we pour,” said Frank Michna of Caledonia, one of hundreds of southeastern Wisconsin residents whose wells are contaminated by pollutants that may be coming from buried coal ash.

Michna’s well is tainted by boron and molybdenum. Molybdenum is a naturally occurring metal that can cause health problems such as gout, a complex and painful form of arthritis, if ingested at high levels. The chemical boron, also naturally occurring, has been shown to cause digestive problems and harm male reproductive organs.

Snow dapples uncovered coal cars in Caledonia, an area where many wells have been contaminated with molybdenum. Photo by Cole Monka / Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

The source of these and other contaminants in the wells could be coal ash from We Energies’ power plants, according to a study released in November by Clean Wisconsin, an environmental advocacy group. Much of the ash has been used as fill in construction projects under a program called “beneficial reuse,” endorsed by the state and federal government.

And it appears that Michna’s predicament in southeastern Wisconsin could be shared by other well owners throughout the state. The EPA has confirmed 157 cases of proven or potential damage from coal ash, including 14 in Wisconsin, and says more will likely be discovered as required groundwater monitoring systems are installed.

In a long-awaited ruling, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency on Dec. 19 labeled coal ash as nonhazardous waste, on the same level as household trash, and established stricter guidelines for disposal and monitoring of ash.

Ann Coakley, director of waste and materials management for the state Department of Natural Resources, said the state’s beneficial use rule, passed in 1985 and praised in the new federal coal ash regulations, puts Wisconsin ahead of states such as Tennessee and Kentucky that have weaker rules.

“For us, we already regulate coal ash as a solid waste,” Coakley said. “This will not be a big change for us.”

The federal rule was largely sparked by the failure of large coal ash storage ponds, especially in southern states. But the rule has implications for Wisconsin because of the volume of ash that is used in construction projects. Those uses will continue to be allowed under the new rule, Coakley said, though there may be some additional restrictions on weight and other aspects of use in building and road construction.

Yet Wisconsin’s contaminated wells raise the possibility that the ash can be far from benign.

In 2011, Clean Wisconsin found, large coal plants produced nearly 1.8 million tons of coal ash. Typically, 85 percent of the ash goes to beneficial reuse, making Wisconsin’s reuse rate the highest in the nation.

Tyson Cook, director of science and research for Clean Wisconsin, said the group focused its study on southeastern Wisconsin because of the availability of data. But coal ash is everywhere, he added, and so may be pollution from that ash.

“There’s no reason to think that it is limited to that area,” Cook said. “It just happened to be where we were looking. In fact, we know that utilities across the state have been selling or giving away their coal ash for these types of uses.”

Coal ash varies a lot. It may be fly ash, fine, gray, talcum-powdery particles that rise with exhaust gases and are captured in chimneys; bottom ash, dark gray leftover material that collects in the furnace; boiler slag, a crystalline material from molten bottom ash and also known as “black beauty”; or sludge, a solid material that forms in a furnace when scrubbers remove sulfur dioxide from exhaust.

The ash is used for concrete, asphalt, wallboard and construction fill in buildings and highways. Contaminants from loose, or unencapsulated, ash can more easily leach into groundwater. In its new rule, the EPA cited the potential risk of using unencapsulated ash but stopped short of requiring more regulation of such uses.

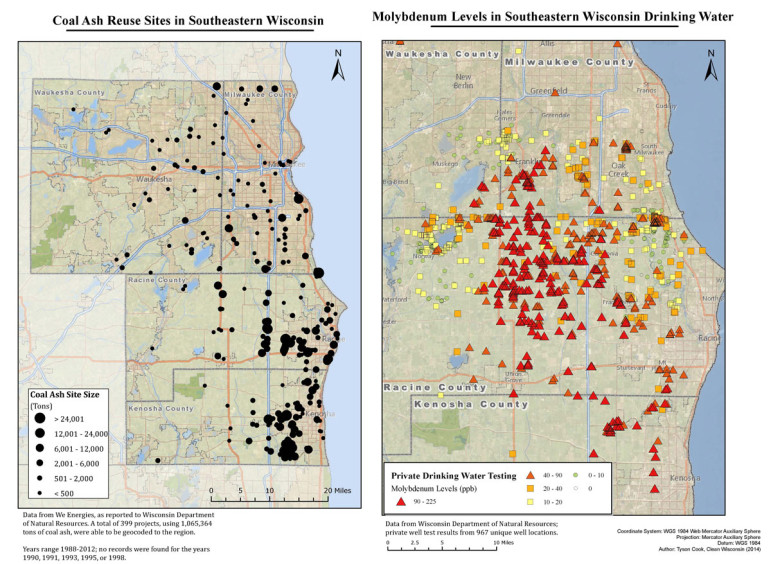

In 2014, Clean Wisconsin, an environmental advocacy group, studied nearly 1,000 private wells in southeastern Wisconsin and mapped 399 coal ash disposal sites. Based on the study, the group said wells closer to disposal sites showed higher levels of molybdenum, a toxic metal found in coal ash. Photo by Tyson Cook / Clean Wisconsin.

-

Wisconsin Lacks Clear System for Tracking Police Caught Lying

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck

-

Voters With Disabilities Demand Electronic Voting Option

Apr 18th, 2024 by Alexander Shur

Apr 18th, 2024 by Alexander Shur

-

Few SNAP Recipients Reimbursed for Spoiled Food

Apr 9th, 2024 by Addie Costello

Apr 9th, 2024 by Addie Costello

There may be many wells that have elevated levels of contaminants, but based on the maps provided in the article, there doesn’t appear to be a correlation between locations of Beneficial Reuse of coal ash and the wells that showed elevated levels of the contaminants. Plus you should at least display the maps at the same scale.

Yeah, I don’t want to rule out coal ash as a possible cause for these contaminated wells, but the correlation is weak at best. Where’s the map showing, say, historic fill sites in relation to contaminated wells? Or historic dumps? Or salvage yards? Or industrial facilities? Or, heck, at naturally occurring mineral deposits?

Now, I agree that more study should be performed. The lack of funding to the WDNR for this specific problem is a failure of government.

I’d argue not that we should do nothing, but that it’s premature to point the finger solely at coal ash.

I wouldn’t say it’s a failure of government, it’s a failure of politics. The job can be done by government but the voters aren’t holding the state government accountable for this.

We get what we deserve.

Politics or government, I agree that the voters need to make their voices heard on the issue. If I have well issues, I’m calling my government representative and make sure I get heard.

That said, repeating those maps above uncritically, does a disservice to a complicated issue. At the very least, you need to separate out the use of coal ash in concrete and asphalt, where it presumably doesn’t leach, from its use as a soil amendment. That’s a flat out basic error that calls into question the whole methodology of the study.

Really, to me it’s looks like they’re trying to fit the facts to a predetermined conclusion. It doesn’t mean they’re wrong, but correlation doesn’t equal causation and even the correlation is not conclusive. The starting point is the wells and an investigation tracing contamination back to a source, not trying to jump ahead and skip the investigation step.

I spent decades collecting well samples for analysis from around coal ash sites and other contaminated property locations. The map above shows there really is little correlation between the ash sites and well contamination problems. Sources could also be old leaky well linings that were never sealed properly and surface water runoff contaminates the well. The source could also be a background level.

There are many pre-1980 fill sites where materials were dumped to fill in a wetland and low area including along major waterways. The materials included foundry sand, incinerator ash, garbage, industrial liquid waste, etc. Milwaukee’s Menomonee Valley and Downtown area included over 1,000 acres of filled properties with humans’ waste debris with layers up to 20-30 feet deep. Many farms had there own private dump sites and allowed industry to fill things on their properties. Southeast Wisconsin was an industrial giant at one time and the buried waste pockets litter the country-side that could be potential sources of well contamination.

A lot more detailed investigation is needed. Regulated landfills are an easy target since we already know they are there but they have also been monitored and designed with best practices. All the unknown sites are really undiscovered and have no monitoring history or identification of the waste product.

Coal was in heavy use as the fuel of choice till the 1960s. Coal ash was spread on roads for de-icing before the start of salting, another toxic material. Homes also used coal for heating and ashes were likely spread on the property. During the 50s and 60s, you could smell the acrid odor of coal burning during the winter times and the snow would turn black with soot after a few days.