Why the Swing Park Failed

It became a comedy of errors, but raises serious questions about the city’s strategy for “creative placemaking.”

It was either an act of vandalism or creative place making, depending on your point of view. On September 9, 2012 an improv-architecture group called beintween, headed up by Keith Hayes, attached swings to the bottom of the Holton Street Bridge and over the “Media Garden,” the public space designed by La Dallman architects.

I am talking about the old fashioned swings, the kind that soar, then hurl you through the air to great heights or thrilling leaps when you jump off. All kinds of them. One swing looked like a raft Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn might have cobbled together, with a homespun solidity that just added to the fun.

People swarmed the place. Swings hypnotize kids and anyone else who needs a break from gravity. Have you ever seen a sad person on a swing?

Brady Street developer Julilly Kohler who spearheaded the creation of the marsupial bridge that connected to the space, was “tickled pink” by the changes, according to Hayes. East Side Alderman Nik Kovac approved. Mayor Tom Barrett’s kids joined the fun and used the swings.

Willie Fields, a retired contractor and member of beintween, oversaw the ongoing maintenance of what soon became known as the “Swing Park,” and documented the project. Beintween monitored their experiment for months to see how the space was being used and make design changes to make sure no one got hurt.

Lots of changes. Cables broke. Attachments had to be retooled to stand up to the stress. This was definitely a work in progress.

All of which created havoc for Ghassan Korban, the Director of Public Works for the city, who normally stays under the radar and fixes stuff like sewers and roads. Fun is not really part of his business.

The Media Garden was a public space, and there were safety concerns and procedures at issue. Someone had to be the adult at the party. Korban also felt the members of beintween hadn’t gone through the right channels, but then, there really aren’t any for this sort of thing.

And so DPW took down most of the swings over the course of several months in the summer of 2013. Korban says he made this decision without consulting the mayor, while mayoral spokesperson Jodie Tabak offers the vague explanation, “we were aware changes were underway, but were not immersed in the details.”

In reaction to DPW’s actions, beintween took down the rest of the swings as a protest.

All of which started an uproar. Websites and a Kickstarter campaign were created to save the “Swing Park.” By all accounts Kovac and Kohler led the charge. The people wanted swings.

Kovac told me there was no time to mess around with design professionals. He pushed a resolution to officially change the name to “Swing Park” though the Common Council. Kovac says he also leaned on DPW to fix this political situation.

Was the mayor consulted? Korban again says no, while Tabak says the mayor had that vague awareness. And at the ribbon cutting for the revival of the Swing Park, Barrett joined Kohler in heaping praise on the “wonderful guerrillas” of beintween. Korban declared, “We delivered on the wants of the neighborhood.”

Said Kovac: “It’s hard to plan for this kind of magic.”

In fact, there was no planning whatsoever. It was proof, it seemed, that everything doesn’t have to come from top down, the plodding old-fashioned way that starts with a plan developed by sanctioned professionals and goes through a formal design and approval process. Sara Daleiden, the point person for the Greater Milwaukee Committee’s creative place-making project who was brought in to work with DPW on the Swing Park, explained that it was an example of “iterative design” — an organic process that grows old and new at the same time.

Think of Hayes and beintween as the anti-Calatrava. Grassroots architecture starts from the bottom up. Rather than running a project through the city bureaucracy, a coalition of community groups made it happen. The result was a Swing Park of the community, by the community, for the community.

To appreciate just how different this process was, it might help to step back and review how the original Media Garden was created. Back when John Norquist was still mayor, Kohler had promoted the idea of building a marsupial bridge tucked under the Holton Street Bridge to connect Brady Street and the Beerline, the Lower East Side and Riverwest. Kohler was active with the Brady Street Business Improvement, which helped drive the project, and Norquist and city planner Peter Park also got involved. Some $3.5 million was spent on it, largely money that came through a federal grant. The La Dallman firm was chosen to design the whole thing.

The project was inherited by Barrett and wasn’t opened until 2006, but had been designed and largely created under Peter Park. The Marsupial Bridge and Media Garden, as it was called, was the culmination of the urban design ethos of its time and set a new standard for public infrastructure for Milwaukee.

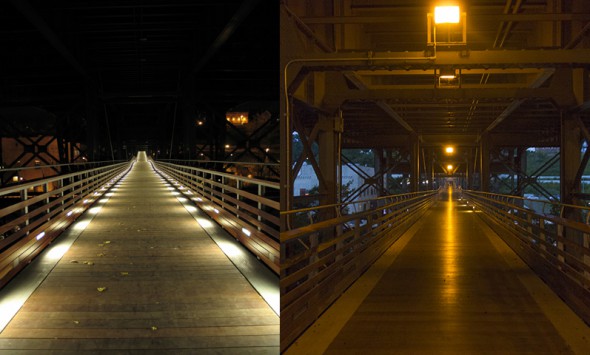

In the daytime, the detailing of the bridge is arresting: a rich gradation of browns and grays pick up the nuances of daylight as it changes. Since the bridge is hung, it undulates naturally, like a landscape. The railings are a delicate weave of steel and wood that shows both materials off to their best advantage. The new bridge added counterpoint, a bit of domestic tranquility to the bold industrial forms underneath the Holton street bridge.

At night, light and shadow weave objects into the ether of a place that was “used” by every person who saw it when they went over the bridge or drove by on N. Water Street. The only other place in Milwaukee where illumination was precisely calibrated to clarify space was a $10 million project — the 600-foot long fountain in the Kiley Garden at the Milwaukee Art Museum before the lights went out a few years ago.

People loved the Marsupial Bridge and Media Garden. Wild Space Dance staged one of its site specific dances there. The project inspired Hayes to finish his education at the School of Architecture at UW-Milwaukee and study under La. It’s prominently featured in La Dallman’s lectures and on Grace La’s faculty page, and undoubtedly figured into her promotion to Harvard last year.

But the work slowly began to deteriorate, starting with the maintenance agreement between DPW and the Brady Street BID. The first thing to go was LaDallman’s down lighting, designed to be hidden so it would not illuminate the bottom of the Holton Street bridge. Eventually the DPW defaulted to the cheapest alternative and added sodium vapor lights, which turned a weightless ribbon of white light into a murky tunnel at night.

It was not a small change. Sodium vapor lights are never used for any outdoor leisure or sales activity — driving ranges, tennis courts, used car lots, or miniature golf courses for example. They were tried and rejected in factories because they depressed workers, lowering productivity. Sodium vapor lights create dead zones we tolerate only at low-value destinations or on the road going someplace else.

Curiously, Korban and Brady Street BID executive Steph Salvia both explained the change exactly the same way — the problem was that a “cherry picker,” an elevated platform on a crane, was needed to replace the bulbs hidden in the Holton Bridge. But they are frequently used by the city, though it takes a certain amount of labor to keep changing the bulbs.

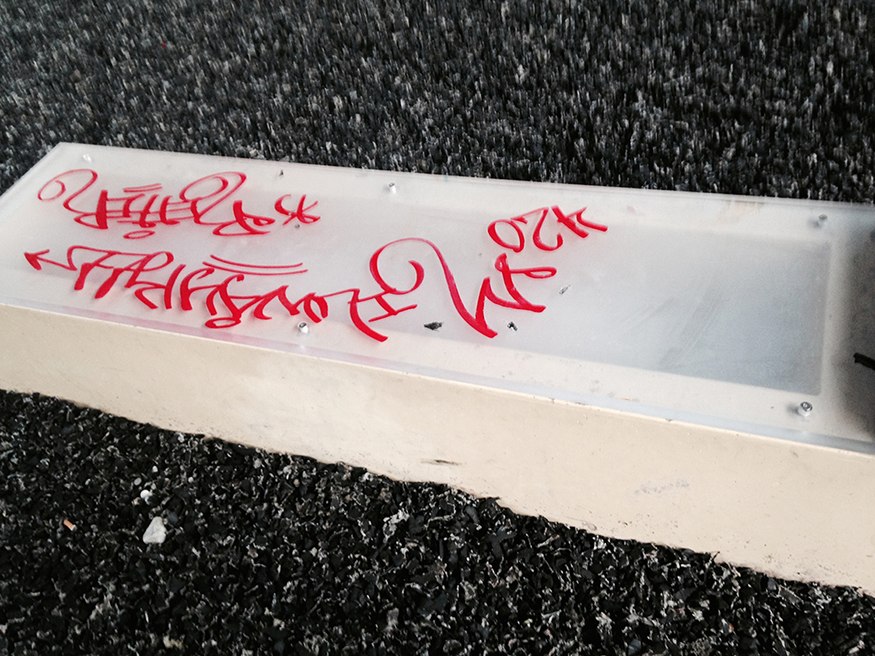

Meanwhile, benches were scuffed up and graffitied. After nearly a decade of neglect the Media Garden needed a lot of work. To bring it back to its original condition would have also cost more money — for either the city or the BID.

Hayes and beintween, in short, were seeking to enliven not the original Media Garden but the version that had deteriorated. They certainly succeeded in doing that, and at very little cost — and no cost to the city or the BID. The materials were donated by Home Depot. But there were those safety concerns about the swings. And so the DPW took the swings down, and then replaced them after the community uproar with a quite different version of the Swing Park.

All without Hayes input. “You are not a park designer,” Korban said, according to Hayes. “We will take it from here. We are liable so we will take care of it.” Though it was a design project, the Department of City Development was kept out of the loop. No models or drawings of any changes were shared with the public.

All concerned say Korban is a nice guy. He seemed sincerely chagrined telling me the project had been “thrown in his lap without a budget.” There was no time to think or resources for testing or any other fail-safe procedure built into a normal design process. “We design and build at the same time,” Korban explains. “Do it as we go.”

That didn’t work out so well. Just a few weeks after the ribbon cutting celebrating the Swing Park’s reinstallation, some of the swings had broke and were removed. The DPW chose the wrong kind of brackets that attached the swings to the bottom of the bridge. Hayes had installed 11 swings, and now just five swings are are there.

Once again sodium vapor lighting was used, giving the park the kind of illumination you might find in an alley.

As for the ground cover, DPW used shredded tire bits, which are thematically related to some of the swings (built with tires) and have the virtue of being recycled. That sounds good in a press release, but makes little sense: a black ground cover in the shadow of a bridge results in too much darkness. Worse, the rubber has a magnetic attraction to shoes and clothes that transports the tire bits all over the neighborhood. It was a mess.

Finally, heavy chains were added to deaden the flight experience. High flying swingers were out of the question. Hayes’ original version used lighter materials so a child could swing as high as an adult. In retrospect, asking DPW to do a swing park was like asking the Army Corp of Engineers to do an opera house.

Weeks after the new Swing Park’s problems became apparent, Korban acknowledged that the lighting and ground cover are under review. The swings still have to be redesigned. “We are now in phase two of the project, Korban says. According to Kovac that is no big deal because it’s a “low ticket item … You go back to the hardware store and fix it.”

Except, of course, for the collateral damage caused by the park’s reinstallation: the destruction of the Media Garden, of Grace La’s nationally celebrated work.

It was like a death in the family. The day after the Media Garden was bulldozed, Korban had the unenviable duty of going to La Dallman’s studio with Daleiden to deliver the bad news. According to La, Barrett also called to express his condolences and say he didn’t know anything about it.

“How could you let this happen?” La asked Daleiden.

“I had too much on my plate, it was a battle I couldn’t win,” Daleiden replied, according to La.

Daleiden won’t exactly say who she was battling with other than that the Brady Street Bid and DPW were involved in the process. When I asked Salvia about this, she told me to talk to Kohler, who did not respond to several interview requests. Then through an intermediary Kohler suggested I talk with Daleiden who later told me, “I did not have a primary role in the decision process.”

Everyone says the intention was to preserve the integrity of La’s design. The best guess is that DPW was in a hurry, came with the wrong equipment, and there was a miscommunication. Hayes theorizes the DPW crew goofed, just “one in a series of big oops,” as he puts it, that plagued the project. “We didn’t have any leadership that looked at the plaza as an asset, Hayes says.”

In our second interview Korban fell on his sword and took “full responsibility” for the outcome. But he would not say who made the decision to bulldoze the benches. Public works projects like this are not supposed to be so mysterious. The demolition of city property, which in today’s dollars is worth $250,000 (as La and others have estimated), is not supposed to happen with no explanation.

By contrast, the stakes are much lower for the kind of “creative placemaking” done by Hayes’ group, because it costs so little. The original Swing Park cost the city nothing and when DPW did its radical redo, there were no architect or artist fees. DPW started with Hayes’s free, full-scale mock up of the Swing Park. There was no vetting process or fussing with details The project cost the city about $26,000, about one-tenth the original cost of the Media Garden.

Maybe the stakes were too low. A real design process would have found a way to integrate the swings into the plaza. La says she could have offered a much better solution in ten minutes if she had been asked. The Media Garden is a vast space. DPW might have had to move a couple of benches or extend some of the swings off to the side of bridge. There is also an undeveloped 200- foot slope to the river.

Or alternatively, the Swing Park might have been created somewhere else in the city. People love swings and the idea would work in many places. Recently an architecture firm in Boston installed a temporary and non-destructive version of Hayes’s swing park that created a “sensation in the Seaport District. People are flocking to the three-acre site adjacent to the Boston Convention and Exhibitors Center, with its set of 20 lighted oval swings.”

Sara Daleiden’s next project, administering the Greater Milwaukee Committee’s new $724,000 grant from the Kresge Foundation (on top of a $350,000 from ArtPlace America) to complete the Artery project, has the same cast of characters. Hayes and company are working with DPW on an abandoned railroad track just south of Capitol Drive.

That’s a big deal, the way public spaces are going to be made in the future. Milwaukee’s recent study, “Growing Prosperity: An Action Agenda for Economic Development,” explains that creative placemaking “transforms cities” while fostering “communication among all the groups needed to make that transformation happen,” including artists, engineers, elected officials, and civic groups.

Except this time around there was no communication between artists and engineers. Elected officials put political efficacy above quality. And civic groups were just window dressing. “The city crushed the process,” says Hayes.

Insiders worry the disconnect between DPW and the creatives will continue on the Artery. Not to mention sodium vapor lights are planned to be installed. If the city wants ideas to bubble up from the “creative class,” then we need genuine collaboration to bring projects to fruition.

Implementing ideas requires an old fashioned design process and a team leader with the authority to coordinate the moving parts. It needs a structure that insulates it from the immediacy of local politics, reaches out to other resources like DCD, and gives everyone more time to think. Especially if Milwaukee is not going to hire professionals, like those who did the High Line in New York or Millennium Park in Chicago.

After the dust settled I asked Korban what he learned working with creative placemakers on the Swing Park.“You don’t hang something from a bridge without permission,” Korban says. “That’s not the proper ways of doing things.”

Kovac offers a wryer version of the same thought: “We are not going to put out a call for people to vandalize public works and hope a transplant from Cleveland (Hayes’ home town) will show up.”

More accurately, you could say the city vandalized itself when it neglected and then destroyed the Media Garden. Hayes didn’t do anything other than have a good idea and execute it better than the city did when it took over the project. If creative placemaking is the future, Milwaukee needs a real design process instead of simply sending in the troops from DPW.

As Hayes puts it, “You don’t have to destroy it to have an authentic dialogue with the public.”

Political Contributions Tracker

Displaying political contributions between people mentioned in this story. Learn more.

- June 25, 2018 - Tom Barrett received $100 from Ghassan Korban

- January 31, 2016 - Tom Barrett received $400 from Ghassan Korban

- November 3, 2015 - Tom Barrett received $400 from Julilly Kohler

In Public

-

The Good Mural

Apr 19th, 2020 by Tom Bamberger

Apr 19th, 2020 by Tom Bamberger

-

Scooters Are the Future

Dec 19th, 2019 by Tom Bamberger

Dec 19th, 2019 by Tom Bamberger

-

Homeless Tent City Is a Democracy

Aug 2nd, 2019 by Tom Bamberger

Aug 2nd, 2019 by Tom Bamberger

So it’s apparent that mr Tom has no concept what creative placemaking is or he just hates it. Creative placemaking brings all party’s to the table. Doesn’t by pass government or peoples that have been involved in the neighborhood. This did all of that. This was Rogue act at first which is fine I love projects like this they need to happen to push boundaries.

Tom just shows how out of touch he is with the creative community and lives in the past and he is most certainly bitter. By no means is this project a failure either. How many pwhole have used this park since the swings ? Thousands? In a roundabout way it is a place now. Just because it’s an engineering challenge doesn’t mean it’s a failure. What a hack article by a hack journalist.

Don’t compare rouge art to creative placemaking please.

There is a big difference however between La’s ‘celebrated’ work and the DPW Tire Swings: People use the tire swings. Even the new swings still get regular use while the benches that La put it sat abandoned. There was a reason the tire swings were put up in the first place.

The question is not why the swing park failed but why La failed. Getting your work in a national art magazine means nothing to the people who are living and breathing in the city. Nobody traveled to Milwaukee to see the bench park and the tire park has gotten much more attention than the benches ever did.

Ghassan Korben has proven to be one of the more creative, open-minded and accessible civic leaders I have worked with in the City of Milwaukee. It is precisely his interest in and advocacy for doing things in new ways that has impressed me. I’m not in a position to comment knowledgeably about this particular situation, but it does seem there can be many perspectives on what happened and why. I think its fair to question our city’s approach to creative strategy with a small “c” just as it is fair to challenge the City with a capital “C”. However, it seems the “city” is interchanged with the “City” a bit indiscriminately here, and I question that. I do think it is all of our responsibilities to consider these issues as a collective city. I’d just hate to see this particular situation disproporationatly characterized as the fault or responsiblity of any one actor.

@Juli I couldn’t agree more. Milwaukee is lucky to have Ghassan heading up DPW. And I thank him for responding to the community, in this case, and many others.

@James & Michael Yup. Swing Park draws people to it daily, it is a success, certainly not a failure.

Julie:

Let me clarify, because I agree with you. In my story I tried to show that Kassan was put in an impossible situation. None of this is Kassan’s fault. He had no support or budget. He was hanged out to dry and fell on his sword like a good soldier. It’s all in the story. I have high regard for Kassan. This is not about persons. It’s the system that failed us, or lack thereof.

Dave and others:

I hoped people who read my article would conclude it was never and either or situation. A swing park is a great idea, and say so in the story.

This is not Grace La and the profession of architecture or a bunch of swings. Both have their place on that site. Keith Hayes and beintween did it with no budget.

If the measure of the success of place is the number of people then the most successful place would be I43 at rush hour. On many nights there were more people at the Swing Park than Lake Park. So?

Dave, I am glad we agree on sodium vapor lights. That is no small thing. Now you see the light.

CLASSIC Milwaukee right here… It’s impossible to have anything inventive or fun for the city.

@Tom People aren’t desiring to go to I43, they are desiring to go home. Yes, indeed the measure of place is creating a place that people desire to be, not simply to create something pretty. My favorite photos from the story, on the left Swing Park (even with those sodium vapor lights), on the right Media Garden in all its glory. But something is missing from the Media Garden… What’s missing?

@Tom Thanks for the clarification. For what its worth, I thought you did a reasonable job conveying the nuances of roles, avoiding finger-pointing while laying out the complexity of the process and interconnectedness (or lack thereof) of the actors in the “system”. I just felt it was worth underscoring that to readers who might jump to different conclusions in their own read of your words. There is a difference between “The CIty of Milwaukee – the government” and “the city of Milwaukee”. In this case, we are saying the “system” is the city – its all of us. These are ideas worth discussion. I appreciate the forum.

Dave:

People loved the swing park and I loved being there too.

There is nothing in my piece that suggests we don’t agree on this point. We should put up more swings in the city…….. god knows we have the space for it.

The fact that DPW put up a swing park that essentially broke down after two weeks of use should concern anyone who loves the swing park as we do.

There could have been a great success story here about the integration of “gorilla” placemaking with the media garden while keeping the space as beautiful as it once was. There was a failure of the system, but it it began with the failure of several key players.

First, the Brady Street BID not keeping up a neighborhood asset for which they agreed to. Next, you have Kovac for pressuring things to go through without fully vetting them or following due processes that are in place for a reason. But I’ve noticed that’s kind of Kovac’s M.O., he has well intentioned ideas but does not always recognize potential consequences. And finally, the DPW for not pushing back, slowing things down, and doing the project the right way.

I love the swings, but this is no longer a place I’m as ready to show off to out of town guests… especially at night.

Is it dangerous at night? Or just poor visibility?

I don’t know if poor visibility is the right way to describe it. Tom’s description is pretty spot on though.

The situation varies from city to city on the issue of passing over city government. In a place like Milwaukee, it seems a bit unwise to do so. In a city like New Orleans, its almost imperative.

I’m still 5 years old inside –sometimes–and even though I’m in my 60’s, I loved swinging under the bridge at night. I love the idea, the creativity and the beauty of the unexpected. I hope people get it together to make sure we keep these projects going. It is the simple things in life that keep us in touch with what is important.

Keith Hayes’s decision to dangle swings from the underside of the Holton Street Bridge was a masterstroke that brought needed attention and a sense of joy to a civic asset — the Marsupial Bridge and the Media Garden. Kids and former kids enjoying the swings 24-7 complemented the special events that brought the Media Garden to life such as the bike-in movie series and dramatic production of the Penelopiad.

What Hayes didn’t do was set up the false choice of swings vs. Media Garden. Tom deserves credit for acknowledging good intentions and thankless roles but also stubbornly questioning the drive to lead with a bulldozer in bringing back the swings. With no budget, project champions apparently felt that anything that slowed down or complicated the return of the Swing Park would have killed it. But that assumption would be a lot stronger if they had accepted offers from Hayes and Grace La (for free?) and explored their design ideas.

@Steve Not for free

I’m glad to see there is general agreement that Tom’s title is just plain wrong: Swing Park is NOT a failure. Is his definition of Failure for a public space failure that more people have probably come to it since the swings went up than in the whole 8 years before? Is it his definition of a failure a failure when it probably helped bring in the $742k Kresge grant for Keith, beintween and GMC to do more of the same? I think the definition of a failure in the design of a public space is that no one comes, no matter how nice looking it is.

I completely agree with Julie Kaufmann that we are lucky to have Ghassan as head of DPW. He is a quick study and gets an idea and its possibilties and has the confidence and courage to work for them.

For he and NIk Kovac to come together and create a city park in order to get proper insurance, engineering and maintenance down there was gutsy, since the City has been giving away its parks rather than creating them. But they saw the popular response and realized this “place” had possibilities that hadn’t been opened until the swings came. They also had to accept that the swings made it a “playground” under federal guidelines, and thor along the swing path and it required certain ground covers– which did NOT include the sharp white marble gravel that was hard to walk on, sit on or push a baby carriage through, much less a wheelchair.

So to legally put in the swings, many of the benches had to go.The benches were picture handsome, but uncomfortable, and were not good for movies since anyone on a bench blocked people behind them.

DPW asked for neighborhood input– and a number of people some forward with interests– parents, flea market proprietors, bikers, skateboarders — a professional skateboard park designer with a design I personally hope can some day be accommodated. Watching these tremendously athletic kids on their skateboards on even the small number of benches that work for them, is wonderful.

@Julilly “I think the definition of a failure in the design of a public space is that no one comes, no matter how nice looking it is.” Yes, I couldn’t agree more with you. To me, people win over pretty (no doubt both can be done but people using a space is #1). Something else about this debate occurred to me, Swing Park is truly an example of place-making as it created an identity for the location, as someone who covers the city I didn’t even remember it was called Media Garden. And I’ve said it before but I’ll say it again, there’s is no doubt that Milwaukee is lucky to have Ghassan heading up DPW. His openness and desire to listen to the community and work to improve Milwaukee is a welcome, and long overdue, improvement.

does anyone care to define “creative?” and yes, i’m waiting for you to do a full magilla on the Nohl house-flap…

I can think of some pretty undesirable places that still attract a lot of people. I don’t think people being present is enough of a qualifier to make a place good. Plus we can’t keep looking at this as an either/or situation. It could have been attractive and attracted people.

Stopped at Swing Park today… I count 8 swings, not 5. 2 Child swings, 1 ADA swing, and 5 adult swings….

If Tom Bamberger thinks Swing Park is great and fun: “People loved the swing park and I loved being there too.

There is nothing in my piece that suggests we don’t agree on this point”, then why did he title his article “Why the Swing Park Failed”? The title will dog Swing Park on the internet forever– which I believe he intended it to do.

It didn’t fail. The space is better and used more than it ever has been. Everyone knows it and it sounds like Mr. Bamberger does too…

And I believe the City is working on a way to restore the Mother swing in some safer configuration.

It’s worth noting that the still-intact marsupial bridge is an essential part of this magical (and pedestrian-friendly) public space. Building bridges (literally and figuratively) is a job for architects and engineers, and cannot be done on the cheap or the fly.

So kudos to Grace La for that elegant design. If now badly lit at night, it still makes for a sweet stroll by day.

We could discuss the merits of the park one way or another but it does not get to the root of the problem of public space design and management in Milwaukee. As a landscape architect and urban designer for 30 years, I have seem the City of Milwaukee shift the emphasis of design and management away from professionals who would recognize some of the issues discussed here. Milwaukee is the largest municipality in Wisconsin and does not have a landscape architect with urban design experience on staff. They have a landscape designer in the department of Forestry. The design of a public space is a complex solution and should have expert stewardship. Public health, safety, and welfare is the responsibility of a licensed landscape architect. Combine that with creativity and vision and you have a smart design process. The solutions should be the result of a collaborative process. Milwaukee is developing their public space by depending on public art grants. This has resulted in temporary solutions.

I have watched in frustration as these projects rapidly develop and often by well-meaning visionaries who may not see the hidden issues that can develop. We do them a disservice by allowing projects to proceed without the advocates in the municipal or professional ranks. I am not blaming the current staff-just pointing out a gap. We are realizing the value of public open space for it’s contribution to our quality of life and the environment. It is about time that the community recognize that we need to act responsibly.

I periodically visit my projects after they are in use. My measure of success is that they are performing and functioning as intended and more. I take great joy in seeing people using the spaces.

Julilly is absolutely right, the swing park did not fail. News stories are meant to get reads, and outrages titles get reads. I would like to see something written about how the swing park worked, why it was a good idea to make this space more appealing and useful,and the drastic change in the amount of people using this space.

$3.5 grant funds spent on some yuppie swingset. The minority-majority areas just get shafted over and over by the white liberal elites who control the purse.