Wisconsin Needs More Contact Tracers

State likely needs an additional 8,000 tracers to respond to COVID-19 spread.

As confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Wisconsin have hit new daily records and hospitalization rates are soaring again, the state is facing a severe shortage of one important resource to help curb the spread of the pandemic: contact tracers.

State and local health departments have been working, sometimes around the clock, to make phone calls and otherwise reach out to anyone who has been exposed to someone who has tested positive for the virus. But the gap between the resources available and what public health authorities say the state needs — especially with the record-breaking spike in cases in recent weeks — is enormous.

By some expert projections, to effectively combat the spread of the virus, Wisconsin needs as many as five to eight times the number of contact tracers currently employed by state, county and local health departments.

“We are having a very difficult time keeping up,” says Kelli Engen, the public health administrator for St. Croix County, which has added 14 temporary employees just to help with contact tracing — a number nearly equal to its full-time-equivalent staff of just under 16 people who run the county’s public health programs under normal circumstances. “With 846 cases since March and nearly 200 active cases currently, we are still drowning,” Engen tells the Wisconsin Examiner.

“Persons who have been told they are COVID positive by their health care provider need to isolate at home, separate themselves from family members to protect them, and not go to public places,” the department’s announcement stated. “Those that have been notified they are a possible contact are also advised to stay home and watch for symptoms, such as fever, cough or shortness of breath. Staying home will help slow the spread to the community, keep our kids safe, schools our businesses open, and our residents working.”

Over the summer, the county had experienced occasional surges of cases that taxed the health department’s 21 contact tracers and another 10 people who help with related work, such as data processing and administrative support, says Judy Burrows, the Marathon County Health Department’s public information officer. But even on the occasional instances they fell behind, a lull would follow and they’d get caught up.

The week of Sept. 14, however, “case numbers started to go up to 20 to 30 cases a day, and that continued,” Burrows says. On Sunday, Sept. 20, “we had 46 new cases, which was a high for us. We were already getting behind for the week.”

Knowing that the department wouldn’t be able to follow up with individual follow-up calls, Burrows put out the county’s press statement the next day.

“When people have been exposed, they need to know that they need to quarantine,” Burrows says. “And if they aren’t alerted that they need to quarantine, they don’t — and that can contribute to spread in the community.”

Community spread

Community spread is public health shorthand for an illness moving so quickly that people who catch it don’t know for sure where they got it.

That’s where COVID-19 is now in Wisconsin — and where it has been since at least March.

And after months in which the number of new cases have risen, then diminished, then risen again, in the month of September the virus has been spreading dramatically.

In the past 10 days, the state has for the first time topped 2,000 new cases a day — not just once, but four times. On Thursday, the state Department of Health Services (DHS) reported 2,392 new, confirmed COVID-19 cases. The total number of people in the state who have tested positive as of data reported Thursday afternoon was 108,324.

That’s more than the population of any city in Wisconsin except for Madison and Milwaukee. It’s more than the number of people who live in any county except the 13 largest ones.

Among college-age people 18 to 24 years old, the rate of infection is five times higher than any other age group, Gov. Tony Evers pointed out at a DHS media briefing on Thursday, and college communities are where the illness has spiked especially dramatically.

To that end, the governor’s office announced a new $8.3 million infusion for private, nonprofit and tribal colleges and universities to conduct COVID-19 testing, funded by the state’s allotment under the federal CARES Act passed in March to provide relief from the impact of the virus.

But while the current spike has been driven by young adults, it’s not limited to them.

“Our campuses don’t exist in a bubble,” Evers said. “By design they are part of our communities, and they welcome students from all over the state and country. So it’s critical that we work together now to get this virus under control, not only to protect our campus communities, but for the health and safety of Wisconsinites in every corner of our state.”

Hospitalizations for COVID-19 have also set a record, with 528 patients in the state as of Thursday, according to the Wisconsin Hospital Association, which posts the data daily on its own dashboard.

“We are entering a new and dangerous phase” of the pandemic, DHS Secretary-designee Andrea Palm said Thursday. Palm urged residents to make flu vaccines a priority this year, “to help prevent the spread of flu at the same time we are already dealing with COVID-19” — while also staying home as much as possible, washing hands frequently and thoroughly to kill germs, and wearing a mask when out in public.

People who have the virus and don’t know it can spread it when they exhale; masks “form a barrier against respiratory droplets that spread COVID-19,” Palm said, which was why Evers signed a health emergency order that took effect Aug. 1 that requires masks, and why he issued a new order Tuesday, Sept. 22.

With the illness spreading so dramatically, contact tracing is even more important to the effort to contain a virus that was unknown a year ago and still has no vaccine, public health authorities say.

It’s so important that several national initiatives to advocate for stronger public health measures have made their own estimates on how many are needed in every state based on a state’s COVID-19 trends.

Since April the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials has been calling for a crash campaign to train and deploy 100,000 COVID-19 contact tracers nationwide, under which Wisconsin would get 1,774.

More recently, George Washington University’s Fitzhugh Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity has created an online tool to estimate what each state needs to have adequate contact tracing. Using a state’s daily case count and other metrics, the tool calculates that Wisconsin needs at least 9,000 contact tracers. A similar calculator constructed by CovidActNow, a consortium of epidemiologists and other health experts at institutions including Georgetown, Harvard and Stanford universities, reaches a similar conclusion — 9,350 “to trace each new case to a known case within 48 hours of detection.”

Currently, including people working for local and county health departments and for DHS, Wisconsin has about 1,240 contact tracers, Palm told the Wisconsin Examiner on Thursday.

Early in the pandemic, DHS set a goal to hire 1,000 contact tracers. Palm said that’s been achieved, with state funding for local public health departments helping some of them add staff for that purpose. A new group of 24 state contact tracers is preparing, Palm said, and more are planned, with another 60 as soon as next week.

In all, DHS has 175 of its own contact tracers and is working to recruit 100 more, with a goal of having 300 by early October, according to DHS spokeswoman Jennifer Miller, providing “overflow, or surge, capacity” for local departments.

“At both the state and local levels, we are maximizing limited resources in attending to the surge in number as well as the increased complexity of cases,” Miller told the Examiner. “While there are national reports suggesting that many states are behind in staffing for this week, we remain committed to responding to the changing needs in a responsible manner – that includes attending to the hiring and training of people who can complete this work effectively.”

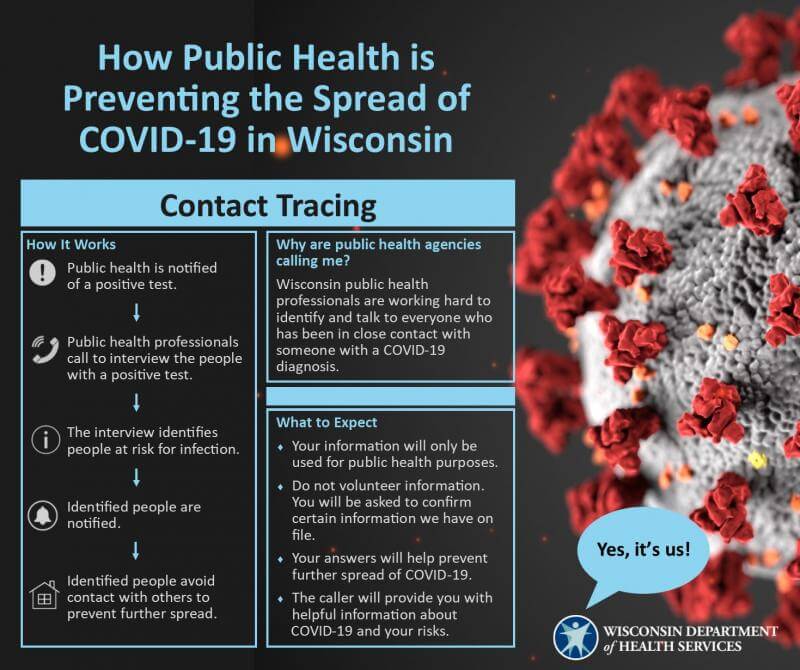

How it works

Contact tracing combines detective work, communication and counseling to help limit the spread of an illness that can be easily passed on to others.

“It’s a tool that we’ve used for a long time for all communicable diseases,” says Karri Bartlett, who supervises contact tracing at Public Health Madison & Dane County. Those include sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, food borne illnesses and more.

Contact tracers interview the person who has tested positive to find out who else may have been in close contact with them and possibly exposed to the virus. Then they contact each of those people to alert them about the potential exposure. They urge them to get tested for COVID-19 themselves and to quarantine for up to two weeks, starting with the time they were last around the original infected person.

With COVID-19, “We don’t have primary prevention tools, like a vaccine,” says Bartlett. “So controlling the spread is our next best option until the primary prevention tools are available.”

“When you ask somebody to quarantine, some of the things they’re going to say is, ‘For how long? What about my kids? What about my elderly mother I take care of?’” Burrows says. “There are all of these nuances in an individual’s life — how do they solve those challenges for the period of the quarantine?”

Tracing all the contacts for an individual case of infection takes time — and more time.

“I don’t know of a county or the state that can say they have enough resources right now,” says Gail Scott, health department director in Jefferson County, “The number of cases has gone up so quickly, and the number of contacts to a case can be 40 to 80 people. In the beginning we would get a case and there might be one or two contacts.”

Selective shortcuts are possible. In a school for example, her department has developed letters to send home when children are potential contacts of a positive case. “It doesn’t always require individual contact,” says Scott.

She prizes strong organizational skills and people skills in contact tracers; while they don’t have to have a background in medicine, they do need to understand how to follow strict procedures that any kind of medically related work requires. A nurse supervises new tracers at the department. “It takes about 30 days to have a contact tracer able to work independently,” Scott says.

A need for speed — and thoroughness

Effective contact tracing starts with fast test results, and fast, but thorough, follow-up.

People who experience COVID-19 symptoms should seek testing immediately and should quarantine, says Bartlett, so that if they are infected, they won’t expose others. In Dane County, the median time between symptom onset and testing is now about one day; the mass testing site that the department maintains at the Alliant Center in Madison helps ensure that rapid response.

The sooner that public health workers know a test is positive, the sooner they can begin contact tracing. And the sooner they reach others who have been exposed, the sooner they can explain why it’s important for those people to quarantine — all in the name of reducing the spread of the virus.

The tracing team also needs as complete a list as possible of the infected person’s close contacts. “The average number of contacts people give us is three,” says Bartlett. That could be appropriate, if the person is adhering guidance to avoid large groups — but it’s also apparent that many people aren’t doing that. Among young adults, “we’ve seen a little more resistance,” she says. “[They] give us their roommates or household contacts, but not everybody they’ve been in contact with.”

Contact tracing is labor-intensive. Before the pandemic, Public Health Madison & Dane County had “a maximum of 10 to 12 people doing this work, for all diseases,” says Bartlett. With COVID-19, the agency has staffed up with more than 100 tracers, usually 40 or 50 working on any particular day, and additional administrative support. “We’re looking to bring on an additional 50 to 80 people in the next few months.”

Much smaller health departments have also staffed up. Some have turned to outside staffing agencies, while others have taken on limited-term, or temporary, employees.

Most of the half-dozen local health directors around the state who spoke with the Examiner have opted to use their own staffs; Scott, in Jefferson County, says her department has contracted for staffing agency employees but conducts its own training.

Engen, the St. Croix County health director, says that when her department needed more contact tracing resources, “I was pretty up front and honest — I would rather see dollars come to our local jurisdiction so we could hire our own.”

The number of potentially exposed people that tracers must contact has been growing, according to some health department officials.

Until recently, “typically it’s the immediate family and a few other people, in the area of 6 to 10,” says Burrows of Marathon County. “That’s a reasonable amount. [But] that number is increasing — it seems that people are going out and doing more, with more people, than they were doing a few months ago.”

And that is one of the biggest reasons that COVID-19 has been surging, health officers agreed. “COVID fatigue has taken over our whole country — everyone is sick of it, and everyone is tired,” says Engen.

Answer the phone

When contact tracers — and other public health workers — call, they don’t know what’s going to happen at the other end of the line.

“Most people we speak with are helpful and respectful, but occasionally that’s not the case,” says AZ Snyder, the public health director for Pierce County.

“We’ve had people swear at us, call us names, and hang up on us. It’s draining when we’re working 12 hour days for weeks on end, desperately trying to protect our community, while being called tyrants or worse. I worry about my staff’s mental and physical health. I worry about local public health’s already-scarce and underfunded workforce being able to make it through this pandemic.”

At Thursday’s media briefing, Palm said that local health officials have told DHS “that contact tracing is becoming more difficult as cases are escalating around the state.”

When the contact tracer dials the phone, “it really is important that folks answer the call,” Palm said. “Provide good, truthful information so that they can do the work … but more fundamentally, that we can do what we need to do to stop the spread — so that there are less contacts, less and less tracing work that needs to be done by contact tracers, so that they do not become overwhelmed.”

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.

More about the Coronavirus Pandemic

- Governors Tony Evers, JB Pritzker, Tim Walz, and Gretchen Whitmer Issue a Joint Statement Concerning Reports that Donald Trump Gave Russian Dictator Putin American COVID-19 Supplies - Gov. Tony Evers - Oct 11th, 2024

- MHD Release: Milwaukee Health Department Launches COVID-19 Wastewater Testing Dashboard - City of Milwaukee Health Department - Jan 23rd, 2024

- Milwaukee County Announces New Policies Related to COVID-19 Pandemic - David Crowley - May 9th, 2023

- DHS Details End of Emergency COVID-19 Response - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Apr 26th, 2023

- Milwaukee Health Department Announces Upcoming Changes to COVID-19 Services - City of Milwaukee Health Department - Mar 17th, 2023

- Fitzgerald Applauds Passage of COVID-19 Origin Act - U.S. Rep. Scott Fitzgerald - Mar 10th, 2023

- DHS Expands Free COVID-19 Testing Program - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Feb 10th, 2023

- MKE County: COVID-19 Hospitalizations Rising - Graham Kilmer - Jan 16th, 2023

- Not Enough Getting Bivalent Booster Shots, State Health Officials Warn - Gaby Vinick - Dec 26th, 2022

- Nearly All Wisconsinites Age 6 Months and Older Now Eligible for Updated COVID-19 Vaccine - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Dec 15th, 2022

Read more about Coronavirus Pandemic here