The Life of Father James Groppi

New documentary captures life and impact of Milwaukee civil rights crusader.

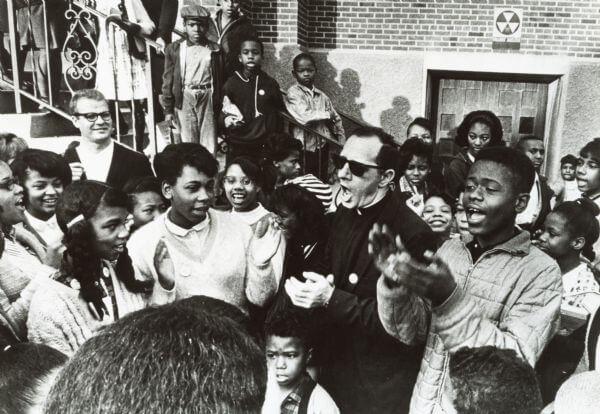

Father James Groppi and students from Boniface School join the public school boycott. They’re clapping their hands and appear to be chanting. Photo credit: Wisconsin Historical Society.

Two Wisconsin documentary filmmakers hope to introduce a new generation of political activists to a Milwaukee civil-rights leader from decades ago, who used civil disobedience to protest unfair housing rules.

In the late 1960s, Milwaukee’s housing laws were set up in such a way that they allowed outright and overt discrimination toward people of color, particularly African American residents.

“Redlining” laws meant the black population was relegated to living primarily within an area of the city called the Inner Core. Close to 90 percent of subdivisions in Milwaukee also had covenants or other agreements forbidding the sale or lease of property to people of color.

A clergyman by the name of Father James Groppi noticed the plight of these residents and took it upon himself to join in their protests, becoming a leader for the cause to reform the city’s rules and policies.

The documentary puts special focus on 200 nights of protests in which Groppi (and other civil rights leaders such as Vel Phillips, who was also a judge and later Wisconsin’s first African-American secretary of state) led black residents into white neighborhoods to highlight the unfair housing laws.

“His story is very compelling, from his upbringing to seminary, as a priest, to the civil rights housing marches,” Rutkowski told Wisconsin Examiner.

The marches began in the city’s Inner Core, crossing the 16th Street bridge (later renamed in Groppi’s honor) into areas where white residents greeted the demonstrations with harsh (and often racist) language. White counter protesters also held signs that suggested Groppi belonged in hell, and frequently greeted his marches with physical violence.

Residents sometimes threw glass bottles at black marchers and wielded clubs. It wasn’t just angry white neighbors, either: Milwaukee police also used tear gas as a means to break up the housing protests.

Rutkowski and Nigro explained why they were making a film about Groppi, noting that there’s a noticeable age cutoff among social activists who know his story, while younger people have never heard of him.

“We’re introducing a story of an activist,” Rutkowski said. “There’s definitely a spirit of activism within this younger generation. I think his story will appeal to those individuals.”

But Rutkowski also said that Groppi’s story could inspire those who aren’t politically active as well.

The film can motivate “those people who are not activists in social justice, to see that this was an individual who wrestled with the definition of what it was to be human, what it was to be a spiritual individual, a Christian and a Catholic,” Rutkowski noted. “So it might bring up some things for people who are maybe on the fence on what to do with what they believe.”

Local lawmakers and social activist organizations agree that much more work needs to be done in the city, in terms of ensuring equality in housing and other racial disparity issues, even though the federal government passed the Fair Housing Act in 1968, the same year the protests Groppi was involved in took place.

“I don’t think things have gotten much better, in fact,” said Rep. Jonathan Brostoff (D-Milwaukee), who represents the district where Groppi grew up. “Basically, the issue is we have a system that’s inherently set up to advantage the people who are already advantaged, and disadvantage the people who are already disadvantaged.”

Erika Sanders, director of program services for the Fair Housing Council in Milwaukee, agreed.

It’s possible that, were he alive today, Groppi would advocate for more protests of discriminatory housing, as well as other forms of discrimination and injustice. Brostoff posits that Groppi might march against the numerous killings of unarmed people of color at the hands of police officers, for instance.

Groppi was, if anything, a proponent of civil disobedience and the rights of people to engage their government directly, taking part not only in the 200 nights of activism for fair housing in Milwaukee, but also protesting in Madison against state welfare cuts, and on behalf of Native Americans in northern Wisconsin later on in his career with actor Marlon Brando.

“We have a right to exercise our Constitutional, God-given right of free speech,” the trailer for the documentary film shows Groppi forcefully asserting. “That means protest, demonstration … whenever we want.”

Filmmakers Nigro and Rutkowski are targeting late 2020 for the release of the film, starting out in Milwaukee theater and branching out from there.

To learn more about the film, or to donate to help with the costs of its production, visit www.fathergroppi.com.

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Because this Milwaukee is so memorable, I’m very much looking forward to the film.