New Charges Against Activist Vaun Mayes

Community organizer says he's being targeted as a "Black Identity Extremist.”

Over a year ago, a federal judge allowed a community activist in Milwaukee, Vaun Mayes, 31, to go home to await trial on charges of conspiring to firebomb a Milwaukee police station in 2016. Since then, his court date has been delayed several times and then last month, federal prosecutors added new charges which accuse Mayes of intimidating government witnesses, planning to firebomb homes in a Milwaukee suburb and using a cell phone to encourage others to riot outside of the city.

Mayes and his supporters say that he’s being targeted as part of the government’s hunt for “Black Identity Extremists,” and as a warning to other activists.

“A lot of this is done as a deterrence factor,” Mayes told Wisconsin Examiner. It’s a potent point, especially with Milwaukee preparing to host the 2020 Democratic National Convention (DNC). Mayes is best known for starting the grassroots organization Program The Parks (PTP). The group provides meals and community activities, and mentors youth in the mostly African American neighborhood of Sherman Park.

Mayes points out that while he has organized many protests and community events, he has never gotten a permit. “This is the fourth or fifth year doing this haunted park party, the fourth or fifth year doing our Christmas drive. We’ve done I can’t tell you how many events, hundreds if not thousands of events in the past couple years where we’ve never gotten permits.”

PTP has received grants from the city and state, but largely relies on small donations from the community. Mayes believes that kind of power and leverage, wielded by an average person, is “scary to a lot of people.”

Milwaukee Stories also reported that Mayes became unpopular with local law enforcement after political demonstrations, including one where he burned an American flag.

Mayes feels he’s become a target because of successes PTP has had without much outside funding, and because of his politics.

“They definitely don’t want me around for next year,” says Mayes. “I’ve been involved in a lot of campaigns in the past three or four years. I’m definitely involved in the mayoral race, a lot of other election races, and they absolutely know that people listen to me. I’m deciphering this stuff to people, and that translates into votes.”

Arisha Hatch, vice president and chief of campaigns for Color Of Change said the kind of government surveillance used to target so-called Black Identity Extremists appears to be an extension of COINTELPRO, the counterintelligence program used by the FBI between the 1950s and 1970s to target black activists including Martin Luther King Jr., the anti-war “new left,” white supremacist groups and others.

“We do understand the attempt to have a chilling effect on activism,” Hatch told the Wisconsin Examiner. “To scare activists away from organizing rallies or demonstrations that are intended to seek justice.”

Color Of Change filed Freedom Of Information Act requests in 2016, “after hearing a growing number of troubling stories from black activists,” says Hatch. Accounts of activists being “followed around grocery stores, identified and arrested before events, along with many other suspicious developments.”

She explained that, at times, federal and local authorities “demonize and intimidate black activists who are rightly demanding that our country be more just, with surveillance and harassment.”

Federal prosecutors would not comment on Mayes’ case. Kenneth Gales of the Eastern District attorney’s office said in an email: “DOJ policy precludes me from further comments with regards to ongoing cases.” Gales also was unable to offer insights into the state’s investigations of Black Identity Extremists.

But police and court documents, and the leaked BIE intelligence report, offer some perspective into the case.

Mayes was arrested and detained for 10 days in July 2018, before being released. A federal judge rejected prosecutors’ arguments that Mayes posed a danger to the community, prompting an emotional outpouring from his supporters in court. The case is pursued by Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) agents, who linked Mayes to an alleged plot to firebomb a Milwaukee police station. The agents claim that the plot was created in the wake of the August 2016 Milwaukee riots, which followed the fatal shooting of 23-year-old Sylville Smith by a Milwaukee Police officer. The riots caused $5.8 million in damage.

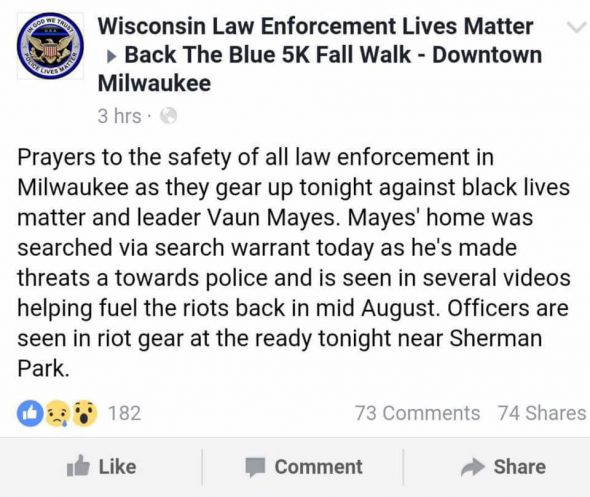

A post from the Facebook group Wisconsin Law Enforcement Lives Matter commenting on the raid on Mayes’ home. Mayes monitored Facebook groups which posted hateful or racist comments and reported them. Photo cataloged by Vaun Mayes on Facebook.

“For me, they’re just looking for someone to pay an invoice right now,” says Andrea Rodriguez, local activist and candidate for county supervisor in Milwaukee’s 14th district. “Honestly, knowing this city and knowing some of the situations that we’ve had, especially with some civil rights lawsuits, I know that they’re not going to rest until someone pays for that.”

A BP gas station was burned in the 2016 unrest along with several vehicles, including a police cruiser. Bus stations were damaged, and looting of local businesses was reported. Riot police from numerous municipalities mobilized to quell the three chaotic nights of riots and curfew from Aug. 13 to 15, 2016. The National Guard was also activated by then-Gov. Scott Walker.

Mayes was out during those nights. Filming the events using Facebook Live, he commented during the live streams that outbursts like riots are the inevitable consequences of decades-long racial inequality. It was also reported by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that Mayes, and other activists, helped diffuse angry crowds. “You’re seeing me protect the police officers,” Mayes told Wisconsin Examiner. “You’re seeing me speak to the police officers. You’re seeing me help and assist them. You’re also seeing me help and save people, help and save people’s property.”

On Aug. 23, according to an affidavit, ATF “was contacted” regarding Molotov cocktails found in a dumpster in the Sherman Park neighborhood. Special Agent Rick Hankins wrote that Mayes was identified by ATF “as a person of interest; and on August 29, 2016, agents conducted a search warrant of Mayes’ residence.”

Hankins stated that “agents located Seagram’s Escape Wine Cooler and Everfresh Juice bottles. These bottles were the same brands of the bottles that were used in the construction of the Molotov cocktails recovered by agents on August 23.”

Mayes says, through his community work, he accumulates glass bottles which are recycled later.

Vaun Mayes with children and supplies for one of Program The Park’s community events. Photo from Vaun Mayes.

A search of another Sherman Park home not connected to Mayes on Aug. 30 yielded, “evidence of Molotov cocktails,” including ripped fabric, gas cans, and “a Mike’s Hard Lemonade, and Seagram’s Escape and Mistic Juice bottle caps.”

The warrant that allowed agents to search Mayes’ home was for devices in his possession which could hold videos, or records such as computers or flash drives. It did not, however, mention supplies or materials to make Molotov cocktails.

On Sept. 20, 2016, agents told Mayes that they suspected bottles used to make the Molotovs originally came from his house. He criticizes the federal agents who raided his home, pointing out that they came looking for his computers, not explosives. Mayes believes they were mostly interested in political statements he made online, and footage he took of the unrest. “They’ll go back and piece a live stream that I did before these dates where I’m talking about black empowerment,” he says.

Mayes was initially charged with possessing and manufacturing Molotov cocktails, and planning to use them to firebomb a police station. ATF considers Molotovs firearms, which no one with a felony record may possess. Mayes was charged in 2005 with driving a vehicle without the owner’s permission. A more recent superseding indictment adds the charges of witness intimidation, using a cell phone to encourage others to riot, teaching others how to make Molotov cocktails, and transporting the devices. All together, he now faces seven separate counts.

Despite the freshly filed superseding indictment, these particular accusations against Mayes of witness intimidation are not new. “When I was first arrested, they tried to use that to deny me bail,” Mayes told Wisconsin Examiner. His attorney, Robert LaBell, argued in 2018 that “the assaultive behavior occurred by someone else … and the government has not provided the information so counsel can confront the people, provide an explanation or challenge the information.” LaBell added, “[Mayes] has been at liberty for two years under the government’s microscope,” During that time he has not been involved in any criminal activity and has cooperated with investigators, his lawyer added, according to court documents.

Prosecutors pointed to the diverse crowd of supporters who flooded the courtroom to vouch for Mayes in 2018 as evidence that he posed a danger. “Defendant has a network; part of that network is in court today,” reads a court document arguing for Mayes’ continued detention. “If he is out of custody what happened in April and June will continue to happen because he will continue to influence others to take severe action against witnesses.” Many of those supporters were local activists and organizers who had worked with Mayes and did not believe the charges against him had merit. Adding to their suspicions was a memo leaked from the Department Of Justice (DOJ) just months before Mayes was indicted.

The document described Black Identity Extremism as a movement motivated to commit violence against police due to “perceptions of police brutality against African Americans.” Critics saw the report as an attempt to mischaracterize and criminalize the Black Lives Matter movement, which began in 2013 and regularly made headlines with protests from 2014 to 2017. Dated Aug. 3, 2017, the memo cited cases of lone-wolf attacks on police officers by African Americans dating back to 2014.

Among the people identified as Black Identity Extremists in the memo were Micah Johnson, who shot 11 police officers in July 2016 and Gavin Long, a former Marine who suffered from mental illness. Long spent a year in Iraq, and shot and killed officers in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Johnson, an Army veteran, was deployed to Afghanistan in 2014. He’d tried joining local black activist groups but was rejected. Long also distanced himself from established activist groups saying in a video he posted, “I thought my own thoughts, I made my own decisions — I’m the one who’s gotta listen to the judgment.”

“Everything that happened in those three days [the riots] is part of my case,” says Mayes. “Like they’re trying to say that I’m connected to all of this, I know all of these people, and somehow someway I’m orchestrating all of this.” He adds, “They’re trying to turn this into Black Identity Extremism and terrorism and validate this with it.”

In June 2017, federal agents issued a warrant to collect DNA from Mayes through saliva swabs. On the way home after providing his DNA, Mayes told Wisconsin Examiner, “when they [agents] brought me back to the house, they asked about the Panthers. Like they kept bringing up the Panthers. And at the time, I had broken out of the Revolutionary Black Panther Party.”

As an activist and woman of color herself, Rodriguez believes the police are inclined to see criminal activity where there is none. “We get together, we organize and make plans,” she told Wisconsin Examiner. “We use anything we can that’s free or accessible, normally social media.” Rodriguez believes activists of color are stereotyped as violent. “They’re always given the thought that we’re angry, or we’re out for ourselves, or just trying to take advantage of people just for being a person of color.”

In some cases, Rodriguez suspects authorities “want to paint people as extremists because they are thinking outside of the box. They’re not necessarily quiet about things that have been happening for decades in our city.” She celebrates the U.S. history of “activist leaders who’ve made great change because they did organize people and it was not with the permission of the city.” Rodriguez says, “if the city were wise, they would be more connected with the voice of the people.”

Prosecutors have provided Mayes’ defense with 32 new discs of evidence to review in discovery. His next court date is set for Dec. 20, 2019. Until then, Mayes continues to live at his Sherman Park home and work in the community through Program The Parks. On Dec. 24, Mayes and company will host a door-to-door toy drive for struggling families in the Sherman Park neighborhood.

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.