New York’s After Care Program Helps Youth

Mentors youth offenders after they finish placement in community facilities. Last in a series.

Young men gather at a community school in the Bronx for a weekly mentoring group as part of their “aftercare,” which aims to help them successfully transition back into the community after spending time in a Close to Home facility. Photo by Allison Dikanovic/NNS.

Although they already face obstacles, the real challenge for young people in New York’s youth justice system comes when they return home, those who work with them say.

“When kids are in placement, they get all these tools, but when they leave, there’s not always people there saying, ‘Hey, stop, think about that,’” said Rohee Ramnath, a mentor for the nonprofit Rising Ground. “But now you leave placement, and you come here.”

“Here” is an “aftercare” mentorship group for youths after they finish their time in a Close to Home facility at a community school in the Bronx. Ramnath is formerly incarcerated himself and is now dedicated to helping youths in his neighborhood turn their lives around.

The Close to Home initiative moved all of the state’s young people from state-run youth prison facilities upstate into community-based programs, and, in some situations, into small residential care homes with limited security measures, in the city.

The organizations that run the Close to Home facilities are all required as part of their contracts through New York City to provide some kind of aftercare for youths. Some homes have mentorship groups. Others have family therapy or other programs.

Initiatives such as Close to Home have gained the attention of leaders in Milwaukee County in the year and a half since the state legislature passed a bill to close Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake youth prisons and replace them with smaller regional facilities, and they will come into question as a state committee allocates funds to replacement plans across Wisconsin in the coming weeks.

In Milwaukee, youths leaving Lincoln Hills or Copper Lake—or even those transitioning home from the Vel R. Phillips Youth Detention Center or a residential care center—have needs when they get home, said Sharlen Moore, the co-founder of Youth Justice Milwaukee, which pushes for alternatives to locking up young people.

Moore has worked with youths, families and community members for more than two years to press for community-based alternatives to incarceration. Her organization is getting ready to launch Youth Justice Wisconsin to push for these kinds of changes at a state level.

“A lot of the young people’s needs aren’t being met once they’re out,” she said. “Young people need mentors, stable housing, jobs and access to transportation to rebuild their lives.” She said these kinds of things should be part of the conversation about how to best replace Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake.

The ‘game-changer’

Meanwhile, in New York, Crook said having the kind of consistent support aftercare provides—and making sure that youths have a supportive adult relationship once they transition back into the community—has been a “game-changer.”

“They really need that person they know they can trust,” Crook said. “They need to know that we’re there for them and that the people they were connected with can answer their phone when they call.”

The Rising Ground aftercare program is modeled after a broader mentoring initiative in New York City called Arches. The initiative is a partnership between the Department of Probation and different nonprofit organizations.

While Ramnath runs his group for youths after they’ve spent time in a facility, Arches is essentially a prevention effort to connect youths and young adults with a supportive community to keep them from getting further into the system. A young person’s probation officer can refer them to an Arches mentorship group, and their time on supervision could be shortened, or their records could be sealed upon successful completion on a case-by-case basis.

Arches and programs like it are run by people considered “credible messengers”—people like Ramnath who have had direct experience in the system themselves and can reflect on and talk about the way they transformed their lives.

Young people volunteer to attend a weekly “credible messenger” mentoring group in the Bronx called Arches, a partnership between the New York City Department of Probation and various community-based nonprofit organizations. Photo by Allison Dikanovic/NNS.

“We’re past just relating to the kids,” Ramnath said. “They don’t just need someone who can relate to what they went through and what they’re experiencing now even. We’re past that. They need compassion, understanding. They need to know somebody’s on their team. They need to know how to love.”

According to a 2018 study by the Urban Institute, Arches participants were significantly less likely to be reconvicted of a crime than youths on probation who did not participate in the mentorship program.

Such mentorship programs are an example of a community-based alternative considered to be a part of a “continuum of care” for youths in the justice system that Milwaukee leaders often mention when they talk about potential reforms.

‘They actually want to help us’

Darnell Davis, who participated in an Arches group in the Bronx, now helps lead one.

“I realized, wow, these people actually want to see us do right,” he said of his surprise when he first started attending the group. “They don’t want to see us in jail cells or unemployed. They actually want to help us. When I found that, I knew I needed to keep coming.”

“These are relationships I’ve never had,” Davis said.

Kevin Quiroz is the Credible Messenger Justice Center liaison at Community Connections for Youth, a nonprofit in the Bronx. He trains other organizations and mentors to run successful mentorship groups.

Ruben Austria, founder and executive director of Community Connections for Youth, and Lisette Nieves, deputy director of programs at Community Connections for Youth, talk about the importance of investing in and building strong communities with a group of youth and families in the South Bronx, New York. Photo by Allison Dikanovic/NNS.

Quiroz said the key to success is strong collaboration between the city-run system and grassroots organizations based in the neighborhoods where the young people come from.

“It’s taking money that was once used to incarcerate individuals and is now used to invest in these community programs, these transformative mentoring programs,” he said.

Youths who may or may not have had interactions with the justice system and their parents choose to participate in a weekly cooking class organized by the nonprofit Community Connections for Youth in the South Bronx to build stronger relationships with each other. Photo by Allison Dikanovic/NNS.

Back in Milwaukee

In Milwaukee County, leaders in the Department of Health and Human Services are working to move kids home from Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake to community-based programs in Milwaukee.

By working through the courts to find alternatives, the county has reduced the number of Milwaukee kids in the youth prisons from 56 youths in May 2019, to 33 youths in August 2019—a 41% reduction.

Mary Jo Meyers, director of the Milwaukee County Department of Health and Human Services, said they began this process of moving kids back to the city because they didn’t want the county’s reforms to wait on the state to close Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake.

“We wanted to start using what we know works right now,” she said. “What does Milwaukee County need to do to reduce the footprint of incarceration for young people, especially young people of color?”

Mark Mertens, administrator for the Milwaukee County Division of Youth and Family Services, said they brought the numbers down by looking at each individual situation to determine what worked best.

Youths have transitioned home or into other local programs. Some have been moved to the Vel R. Phillips Youth Detention Center in Wauwatosa to participate in the Milwaukee County Accountability Program—a partnership between the county and nonprofit Running Rebels. Others were referred to social services through the county program Wraparound. And others were referred directly to Running Rebels’ mentorship and supervision programming.

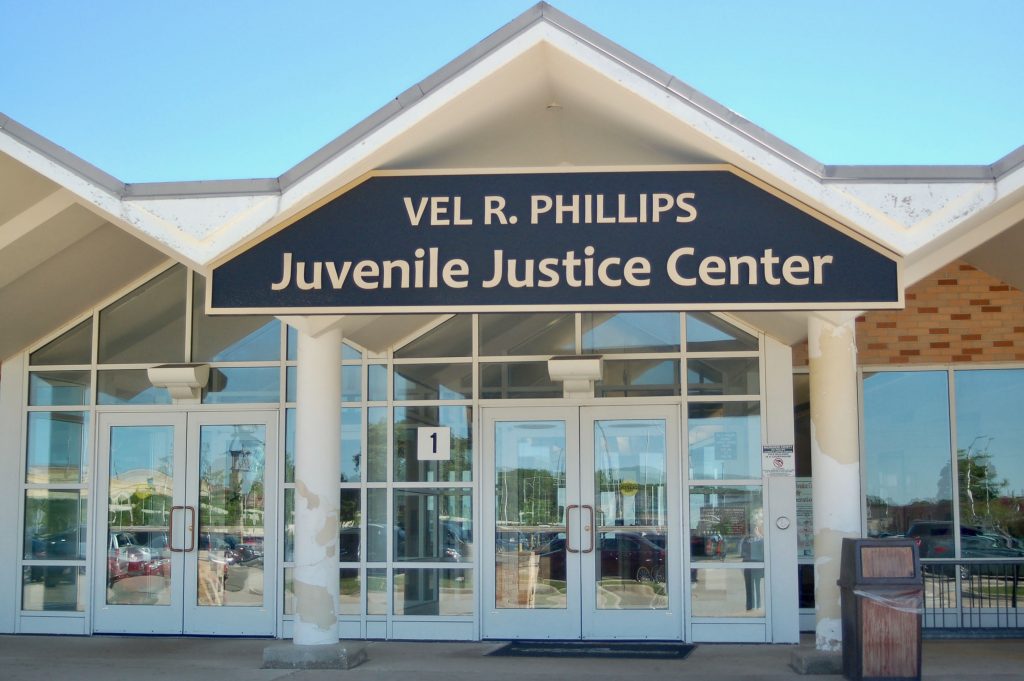

The Vel R. Phillips Juvenile Justice Center in Wauwatosa houses the Milwaukee County Children’s Court, a detention facility and school for youth. Photo by Andrea Waxman/NNS.

As it continues to implement reforms, Mertens said Milwaukee County will continue to utilize Bakari Center as a residential option for youth in the justice system.

The center—which opened earlier this year— is a therapeutic residential treatment center for boys. It uses individual and group therapy to teach young people how to regulate their emotions and make thoughtful decisions.

Milwaukee County leaders have said alternative programs and models like Close to Home are some of the inspiration behind their recently submitted $24.9 million proposal to the state for the local piece of the plans to replace Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake.

“We’re asking what can we learn from what we’re doing now and from the places that we visited like New York and Washington, D.C.?” Myers said.

Last week, Milwaukee County updated its plan to reduce the number of beds it plans to have for youths from 54 to 40. It also reduced the proposed costs of renovations for facilities from $41.8 million to $24.9 million.

The county’s new proposal doesn’t include building any new facilities but rather suggests renovations and new programs. It seeks to renovate the Vel R. Phillips Youth Detention Center to feel more homelike, with added green space and accessibility for families, and suggests the county will collaborate with, lease and renovate existing residential facilities in the county through partnerships with “community partners” that haven’t been identified yet.

[inarticlea ad=”UM-In-Article-2″]The rest of the requested funding—in addition to separate county funding—would be dedicated to investing in personnel and staff training as well as creating more programs to serve as alternatives to incarceration, including mentoring programs.

Other counties in Wisconsin have also proposed plans for local youth justice programs—including building new facilities and expanding detention centers. A state grant committee will determine who will receive funding in October.

Meanwhile, as part of the law that will close Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake, the Wisconsin Department of Corrections plans to build a youth prison in Milwaukee on Teutonia Avenue and one in Hortonia, Wisconsin—separately and independently of the county’s plan.

The two prisons would be for young people who commit more serious offenses and are deemed “Serious Juvenile Offenders.” Additionally, the state plans to significantly expand Mendota Juvenile Treatment Center, which is a secure correctional facility in Madison, increasing the number of beds across the state for youths in the justice system.

Moore and other stress that now is the time for Milwaukee to explore other alternatives to incarceration.

“We’re hoping that we start doing some things differently,” said Moore of Youth Justice Milwaukee. “Not locking young people up just because it’s the easy thing to do, but that we literally start practicing best practices and stop locking up young people.”

Editor’s note: Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service has changed the names of youths in New York’s justice system upon request to ensure their safety and privacy.

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on eighteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.

More about the Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake Facilities

- MKE County: See Inside New Juvenile Detention Facility - Graham Kilmer - Mar 5th, 2026

- State Juvenile Prisons Finally Complete Court-Ordered Reforms - Graham Kilmer - Jan 28th, 2026

- Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake Youth Facilities Found in Compliance, Triggering End to Court-Ordered Monitoring Set in Place by 2017 Lawsuit - American Civil Liberties Union of Wisconsin - Jan 28th, 2026

- Gov. Evers, Doc Celebrate Completion Of Successful Reforms at Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake Schools - Gov. Tony Evers - Jan 28th, 2026

- Gov. Evers Announces State Building Commission Approves Approximately $185 Million in Projects Across Wisconsin - Gov. Tony Evers - Dec 17th, 2025

- Building Commission OKs Planning Funds to Reorganize Wisconsin Prisons - Sarah Lehr - Oct 29th, 2025

- State Building Commission Releases Funding Gov. Evers Requested to Revamp Corrections Facilities - Gov. Tony Evers - Oct 28th, 2025

- Gov. Evers Announces Evers Administration to Move Forward with Comprehensive Plans to Revamp Corrections Facilities - Gov. Tony Evers - Oct 14th, 2025

- For The First Time, Wisconsin’s Youth Prisons Are Fully Compliant With Required Reforms - Rich Kremer - Oct 3rd, 2025

- Inmate Sentenced For Role in Youth Counselor’s Death at Troubled Prison - Isiah Holmes - Aug 11th, 2025

Read more about Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake Facilities here

Close to Home

-

Building Trust Can Help Juvenile Offenders

Sep 11th, 2019 by Allison Dikanovic

Sep 11th, 2019 by Allison Dikanovic

-

How New York Handles Juvenile Justice

Sep 10th, 2019 by Allison Dikanovic

Sep 10th, 2019 by Allison Dikanovic