Thrills on the Wells Street Viaduct

For 60 years streetcars rattled across the 2,085-foot-long bridge, 90 feet above the Menomonee River Valley.

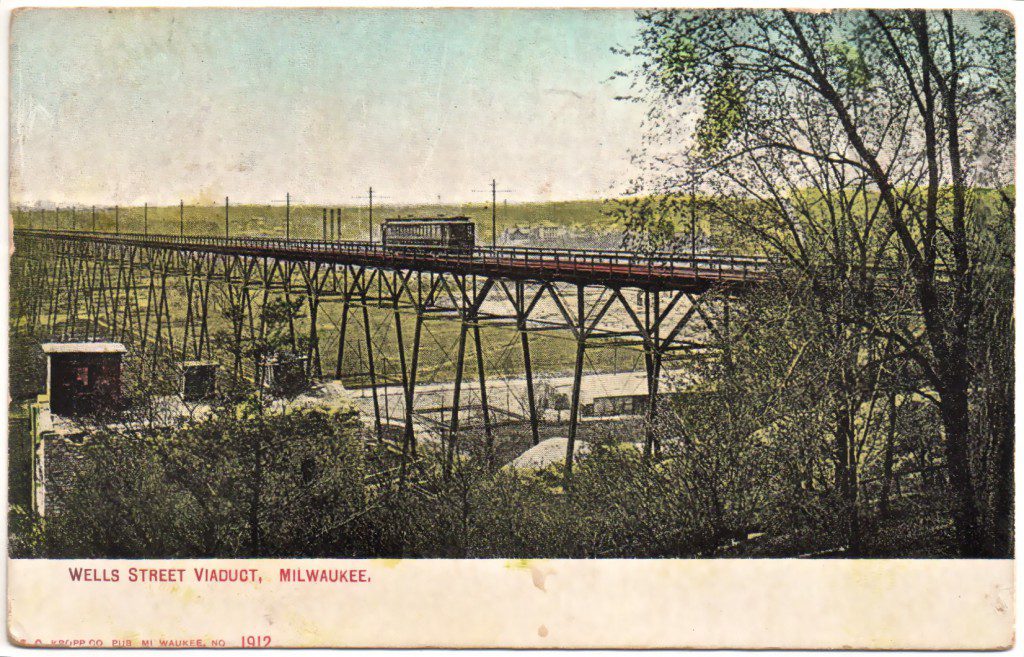

A postcard, dated 1909, shows a streetcar crossing the viaduct. The 2,085-foot-long Wells Street viaduct was the Milwaukee streetcar system’s greatest engineering feat. Built in 1892, it remained in service until the end of trolley service in 1958. Photo courtesy of Carl A. Swanson,

Enjoy this sample chapter from the book, Lost Milwaukee, by Carl Swanson, published by the History Press.

Nothing remains today, but for 60 years, the Wells Street viaduct was a Milwaukee landmark and the single greatest engineering achievement of the city’s once-vast streetcar and interurban empire.

As a thrill ride, albeit an unintentional one, the viaduct had few equals – especially when high winds buffeted the cars. Even veteran riders felt apprehensive as their streetcars rattled and swayed across the rickety-looking 2,085-foot-long bridge, 90 feet above the Menomonee River Valley.

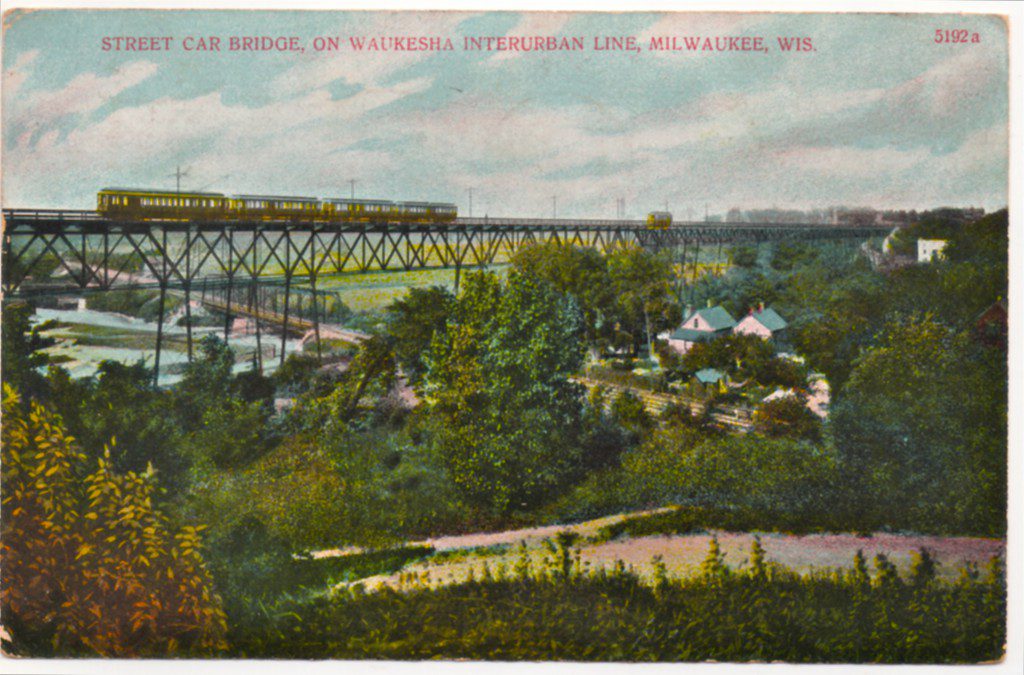

In this postcard view, a heavy four-car electric interurban train rolls across the Wells Street Viaduct in the early 1900s. Photo courtesy of Carl A. Swanson.

The Milwaukee & Wauwatosa Motor Railway Co. was formed in the 1890s to build and operate a three-mile-line between the intersection of North 36th and West Wells streets and West Main Street in Wauwatosa, along with a two-mile branch into West Allis. The Motor Railway awarded a contract in 1892 to construct the viaduct across the wide Menomonee Valley.

Although 1.3 million pounds of steel and a half-million pounds of timber went into its construction, many Milwaukeeans thought the bridge looked ridiculously flimsy. In fact, its Victorian-era designer, Gustave Steinhagen, relied on excellent engineering rather than overwhelming mass. His bridge was amply strong enough to accommodate even very heavy four-car electric interurban trains.

Built wide enough for two railroad tracks, the bridge opened with a single track and a one-lane toll road for pedestrians and wagons. The bridge was soon double-tracked, and the Motor Railway became part of the Milwaukee Street Railway Co. In 1897, the Street Railway and the several other privately owned lines merged to form the Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Co.

In 1938, Wisconsin Electric Power Co. took over operation of what was simply known as The Electric Co., which, in turn, operated streetcars under a subsidiary called, logically, The Transport Co.

Thanks to careful maintenance and cautious operation (for a time, signs at both ends of the bridge sternly reminded motormen they were forbidden to cross the valley in less than two minutes), there was never an accident on the viaduct, not even a minor derailment.

Certainly there were plenty of odd occurrences. The viaduct seemed to have an almost hypnotic appeal for drunken drivers. On several occasions inebriated motorists attempted to drive across the viaduct. Generally these adventures ended quickly and their broken vehicles had to be towed away before streetcar service could resume. On at least two occasions intrepid – and almost certainly stewed-to-the-gills – drivers made it all the way across, their cars bouncing along from one tie to the next high above the valley leaving a trail of shredded tire pieces for railroad workers to find the next morning.

On the night of June 7, 1946, a streetcar motorman spotted a fire in the 13-acre Hilty-Foster Lumber Co. yard located under the viaduct. He notified his dispatcher, who called the fire department.

The fire, possibly caused by an explosion of stored benzine, was already out of control when the first firefighters arrived and the blaze quickly grew into a five-alarm inferno destroying 4 million board feet of lumber, a box shop, planning mill, two warehouses, four lumber sheds, and 18 boxcars. Twenty-one fire engine companies and eight ladder trucks – more than half the city’s fire equipment – fought the fire.

Surrounded and at times almost hidden by swirling flames, the viaduct’s wooden deck soon ignited and, after burning for hours, collapsed into the valley below. Streams of water played on the burning bridge caused the super-heated steel to warp and twist. Service was suspended for five days while an army of workers from the Transport Co.’s Way and Structures Department repaired the damage.

The Transport Co. completed the change to buses in late 1957, but streetcars continued to serve the Wells Street line into early 1958. It was a temporary reprieve caused by uncertainty over the continued control of the viaduct. The wording of the original property easements clearly specified the viaduct was for streetcar use. Realizing the legal justification for the viaduct’s existence ended the instant the last streetcar rumbled across, the company kept the Wells line going a few additional months while it pondered its options.

The Menomonee River Valley was a major bottleneck for east-west traffic in the years before the freeway system. Running transit buses over a rebuilt viaduct seemed an appealing option for a time, but nothing came of it.

Finally, on March 2, 1958, the Wells cars made their final runs. The viaduct remained in place for a few years while the city considered a plan to covert it into a vehicular bridge for a proposed east-west highway. The completion of the Interstate ended this idea and bridge was dismantled in 1961-62.

This former Milwaukee Electric Railway and Transportation Co. electrical substation still stands at the intersection of 36th and Wells. The road at left leads to the east end of the former viaduct. Photo courtesy of Carl A. Swanson.

Carl Swanson is the author of the book Lost Milwaukee from The History Press, available from book stores or online.

Lost Milwaukee

-

When Police Handed Out Courtesy Cards

Jul 14th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

Jul 14th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

-

Riverwest Had World’s Largest Color Printing Press

Jun 11th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

Jun 11th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

-

The Mighty Grand Avenue Viaduct

Apr 29th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

Apr 29th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

In the 50’s, the fare was $0.10 and I enjoyed every single trip across that thrilling span.

blurondo: At that time, it was also the best way to get to the new County Stadium when the recently arrived Braves were the biggest thing to happen in the history of the whole world, including Wauwatosa.

I’m curious about the second post card image. Which interurban route might have been using the Wells St. Viaduct? I understood that interurban trains used the right of way that paralleled today’s I94 (you can still see various electric line towers with space for the trains to run underneath).

Those who oppose the new streetcar, fail to realize that the city of Milwaukee (and surrounding suburbs) developed along streetcar lines. The streetcar lines radiated out from downtown like the spokes of a bicycle wheel. Major roads today still follow the old streetcar lines (Kinnickinnic, Lincoln, National, Forest Home, Wells, Lisbon, Fond du Lac, Teutonia, Green Bay).

Streetcars were replaced by internal-combustion cars and buses because US auto makers and oil companies used their considerable political clout to put streetcars out of business and not because they were inefficient.

@“45 years”, in the 1930s, there were 3 east-west electric rail lines near today’s Miller Park: the streetcar tracks on Wells, the interurban where I-94 runs today, and another streetcar on National Avenue.

Just east of Calvary Cemetery (around today’s 52nd St), a north-south branch split off the streetcar (using private right-of-way) to connect with the interurban line. When it met the interurban line (today’s I-94) the streetcar followed the interurban (I don’t know if it used the same tracks or an adjacent one) until 70th St where the streetcar turned south toward Greenfield.

By the time County Stadium opened in 1953, the National Avenue streetcar and the interurban no longer operated, but both branches of the Route 10 Wells Street streetcar continued. The streetcar company even built a new station to serve the County Stadium.

(The above came from the book “T.M./The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Company” by Joseph Canfield.)

Blurondo, the fare in the 1950s (the late 1950s, anyway) was 20¢ for adults (or 6 tickets for $1) or 10¢ for children under age 12 (6 tickets for 50¢).

To “45 years in the City “–

Interurban routes that crossed the valley on a separate pair of rails South of the Wells Street trestle served Watertown (including Waukesha, along this line), Burlington and East Troy (and points between). The Watertown line branched off from the East Troy and Burlington lines at West Junction (near what is now I-894/100th street/Rogers St. in West Allis). The East Troy-Burlington lines continued to Hales Corners where they separated at St. Martins to continue separately to their end points. I-94 today West from downtown across the valley is where these high-speed interurban lines operated (parallel to the Wells Street #10 street cars that served West Allis and Wauwatosa).

36th & Wells substation photo caption correction: The company was The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Co. (TMER&L).

A little background about the sentence starting with “In 1938, Wisconsin Electric Power Co. took over operation of what was simply known as The Electric Co.” The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 mandated utility companies to divest public transit systems. The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Co. (TMER&L) was reorganized in 1938 as the Wisconsin Electric Company, which spun off its transit operations into a subsidiary, The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Transport Co. (TMER&T), marketed as the Transport Co. Wisconsin Electric offered to sell the Transport Co. to the City of Milwaukee in 1946, but the Common Council declined.

TMER&L opened a grade-separated Rapid Transit line in 1926-1930 from 8th & Clybourn to West Junction (power lines paralleling I-894 at Burnham) to remove interurbans from increasingly congested streets and renamed interurban service as Rapid Transit on their maps (1931 map, https://content.mpl.org/digital/collection/MKEMaps/id/33/rec/2) and PR. Construction started on a Downtown subway in 1930 to remove Rapid Transit from Downtown streets during the first full year of the Depression, but work was suspended as the Depression worsened (Milwaukee Sentinel, “City subway almost made it,” August 20th, 1977, https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=iY5QAAAAIBAJ&sjid=5BEEAAAAIBAJ&pg=6389%2C3727821).

To TransitRider, the Rapid Transit line was four-tracked between Soldiers Home and 68th. The West Junction Local, Watertown, East Troy and Burlington Rapid Transit interurbans ran express on their tracks between Soldiers Home and 68th (no Hawley stop), while the West Allis branch of the #10 Wells-Downer car line made local stops (e.g. Hawley) on its own tracks.

When the Braves arrived in 1953, the shortened Wells line already had a stop at Soldiers Home (County Stadium). They laid a third track on the abandoned Rapid Transit line to store 10 cars for the crowded ride home.

To “Edward S”

What you write matches my understanding. The image of an interurban on the Wells St. viaduct post card must have been “artistic license”. Thanks

To 45 years in the City and Edward Susterich, the four-car train interurban on the Wells St. Viaduct might be “artistic license,” but it’s based on fact. The Watertown line shared trackage with the West Allis branch of the #10 Wells-Downer car from Downtown to West Junction (power lines paralleling I-894 at Burnham) from 1899 to 1910, per Joseph Canfield’s “TM, the Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Company” (Plate 2), https://encore.mcfls.org/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1859660.

The Watertown line was rerouted to share trackage with the #18 National-Fond du Lac line from Downtown to West Allis, then continued onto the West Allis branch of the #10 car to West Junction in 1911 before being relocated to the Rapid Transit line in 1926, http://mpl.org/blog/now/a-hymn-for-the-rapid-transit-interurbans.

The postcard is a cropped version of a postcard reproduced in black-and-white in Greg Filardo’s “Old Milwaukee: A Historic Tour in Picture Postcards” (p. 103) https://encore.mcfls.org/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1723812. I don’t know if the postcard in Filardo’s book is originally black-and-white or color, but it looks like a photograph or at the very least, a hyperrealistic illustration on the lines of David Lenz’s paintings.