Risking Their Lives for Fair Housing

The courageous protests of Fr. Groppi and the NAACP Youth Council.

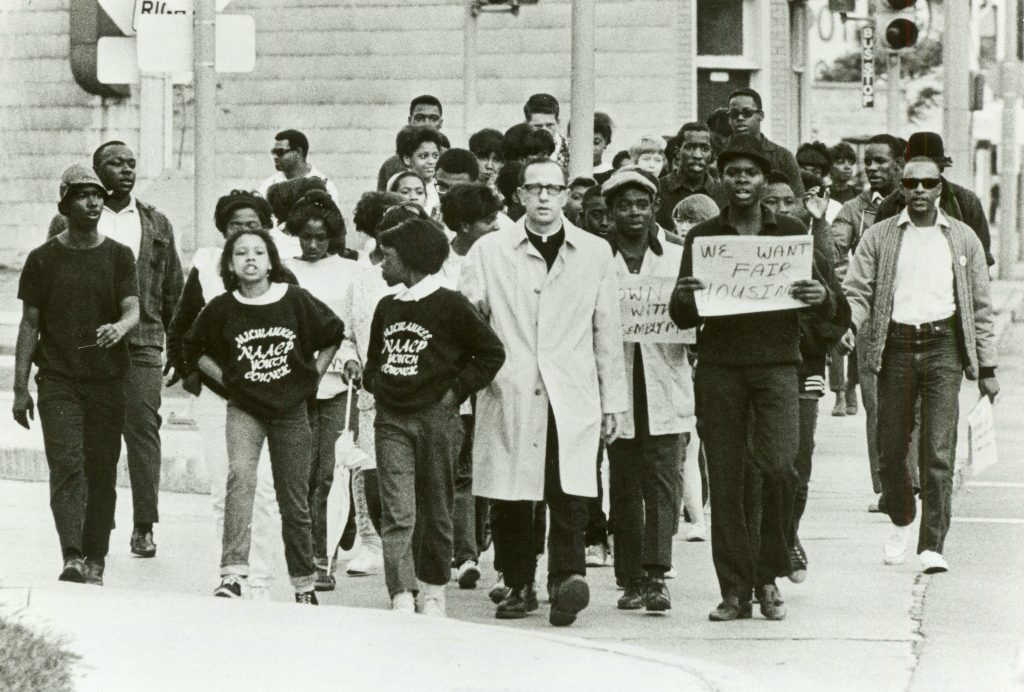

Father James Groppi and members of the NAACP Youth Council march in support of Vel Phillips’ open housing bill. Photo courtesy of Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and Historic Photo Collection, Milwaukee Public Library.

On Aug. 28 and 29, 1967, civil rights marchers from Milwaukee’s largely African-American North Side crossed the 16th Street Viaduct en route to Kosciuszko Park on the city’s predominately white South Side.

Led by the Rev. James Groppi, advisor of the NAACP Youth Council, and its Commando security unit, 200 council members and supporters marched to protest housing discrimination.

On the first night, the protesters were met by thousands of hostile white counter-protesters at the south end of the bridge. Five thousand counter-protesters, waving signs bearing racist epithets and jeering, followed the marchers to the park and shouted them down. On the march back, the white mob threw stones and bottles.

“We nearly got killed there last night,” said Groppi, a white Catholic priest, in a televised press conference the next day.

Announcing that the Youth Council would march again that night, Groppi said, “We have tried every means possible to bring fair housing legislation to the city of Milwaukee and we’re going to continue to march. … We’re going to exercise (our constitutional right of freedom of speech) regardless of … the danger. We’ll die for that right.”

“By the time the marchers (returned to) the safety of the viaduct, they looked like refugees from a battle. … Some could not walk and had to be carried by other marchers,” wrote Milwaukee Journal reporter Frank Aukofer in his book about the local movement, “City With a Chance.”

Shortly after the Youth Council’s return to the NAACP headquarters at Freedom House, 1316 N. 15th St., tear gas and bullets from police rifles engulfed the area and the house, setting it on fire. Those inside escaped but the building burned down. Police said they were responding to reports of a sniper, a claim Groppi and the Youth Council disputed.

Mayor Henry Maier called for a voluntary curfew and prohibited night marches for 30 days. Instead of marching, the council held a rally in front of the Freedom House ruins the next evening, but police ruled the gathering illegal and arrested more than 50 people. Council members decided that if they were going to be arrested anyway, they might as well march.

Groppi, the Youth Council and their supporters ended their protests for open housing on March 14, 1968. “Demonstrations, in the form of marches and rallies, had continued for 200 consecutive days since that first tense walk to Kosciuszko Park on Aug. 28, 1967,” wrote Aukofer. Open housing laws had been passed in 17 communities but would not pass in the city of Milwaukee for another month and a half.

Three weeks later, on April 4, as the Youth Council considered how to proceed, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated and the nation erupted in grief and violence.

Choosing to honor King’s commitment to non-violence, the Commandos and Groppi organized a march through downtown Milwaukee that culminated in a rally on the North Side. “Over 15,000 people joined in that march, the largest in the city’s history and one of the nation’s largest memorial demonstrations for King,” wrote Groppi’s widow and Youth Council member Margaret Rozga.

Growing frustration

Tensions in Milwaukee had been growing throughout the early 1960s. Activists had taken on the issue of school desegregation with the city’s first major civil rights demonstration, organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), in 1963. The following year, African-American attorney Lloyd Barbee brought more than a dozen civil rights, political, labor, religious and social groups together to form the Milwaukee United School Integration Committee (MUSIC) to fight segregation in the public schools, including a large-scale boycott of black schools. In 1965, Barbee filed a federal lawsuit against MPS.

The Youth Council began its first big civil rights campaign in February 1966 when it picketed the whites-only Eagles Club and some of its members’ homes.

Frustration with the lack of civil rights progress in the African-American community, and fear and anger among whites continued to escalate in the summers of 1966 and 1967.

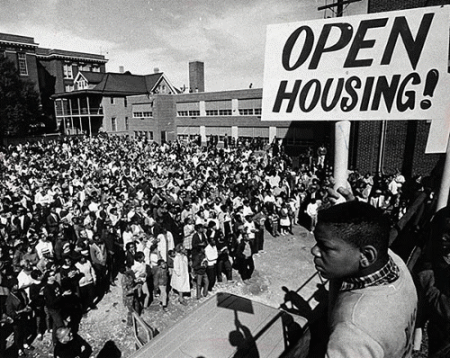

Open housing demonstrators gather at St. Boniface Church. Photo courtesy of Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and Historic Photo Collection, Milwaukee Public Library.

In addition, Milwaukee’s black youth were hearing the call of the nascent black power movement, popularized nationally by leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which spoke of black dignity and self-determination.

On Aug. 9, 1966, Ku Klux Klan members threw a bomb into Freedom House, the NAACP headquarters then located at 2026 N. Fifth St. The incident caused minimal physical damage but raised concerns about threats to members’ safety.

Spurred by distrust of the police, the Youth Council’s direct action committee had formed the Commandos in 1966, a security force committed to protecting marchers without provoking violence.

“Once the Commandos got involved with direct action … they managed to … dramatize this issue of open housing. It placed the spotlight on segregation in the city for the first time,” said Erica Metcalfe, a history professor at Texas Southern University, who conducted research on the Milwaukee Marches at UWM.

Calling the Youth Council “the best in the country,” Metcalfe added, “It stood out as one of the most active and (many of its members) were just high school kids.” Most of the Commandos were in their mid-20s, she said.

On July 30, 1967, just weeks after riots raged in Newark and Detroit, disorder broke out on Milwaukee’s North Side and spread downtown. Sparked by a confrontation between police and a crowd of black citizens outside a nightspot, looting, gunshots and arson reigned for two nights. There were four deaths, hundreds of injuries and more than 1,000 arrests, prompting Mayor Henry Maier to call up the National Guard. He imposed a dusk-to-dawn curfew that lasted for more than a week.

Housing conditions

According to the Wisconsin Historical Society, Wisconsin’s African-American population increased by nearly 600 percent in the decades prior to the marches, from 12,158 in 1940 to 74,546 in 1960. Urban renewal efforts started after World War II had taken a toll on African-American neighborhoods and housing. The destruction of many older homes and the clearing of a wide swath to build Interstate Highway 43 put particular stress on housing availability. Redlining, restrictive covenants, block busting, predatory lending and insurance practices all contributed to the problem.

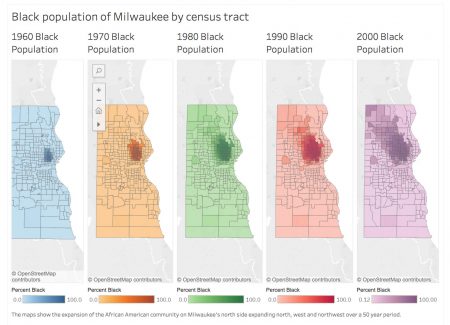

Graphic by Jack Goods. Republished with permission from “Marching On: 50 Years After the Milwaukee Marches,” a project of Professor Herbert Lowe’s journalism capstone class at Marquette University’s Diederich College of Communication. Click on the graphic for more details.

Alderwoman Vel Phillips had led the charge to end housing discrimination when she introduced a bill in the Milwaukee Common Council that would outlaw housing discrimination in 1962. The council failed to pass it then and all three times she re-introduced it between 1963 and 1967. Phillips cast the only vote for the bill every time.

In late 1966, Groppi informed the Youth Council that black Viet Nam war veteran Robert Britton had reported that he and his family were barred from renting an apartment at 29th and Burleigh streets on the basis of race.

The council then joined forces with Phillips to support a citywide open housing ordinance.

The viciousness of the counter-protesters was a critical component of the marches, said UWM history professor Robert Smith.

“[The counter-protesters] thought about how to be offensive. They thought about how to create the most hostile environment both in terms of their speech … and their actions and also in their physical violence,” said Smith, who noted that this behavior was not punished.

Smith added that powerful expressions of resistance on the part of counter-protestors generally embolden and reaffirm those who are demanding fair treatment.

“Even in the face of physical violence, and death and maybe losing jobs,…those hostile responses in many cases lead the protestors to find a level of resolve — and this is where marching and singing and prayer come into play — a place of peace in which they no longer fear what will happen.”

Former Commando Fred Reed agreed that as insults and injuries to marchers increased, the number of participants grew.

[inarticledad ad=”UM-In-Article-2″]Smith also pointed to a unique convergence of forces in Milwaukee that shaped events. “That particular moment in the history of the city’s longstanding set of campaigns for equality is … an interesting merger of traditional civil rights activism that we associate with the South and a much more radical, boisterous expression that we associate with the North.”

The talents of leaders such as Phillips, Barbee, Groppi, the Commandos and others led to “intersecting approaches to advancing a civil rights agenda that came together very beautifully in Milwaukee,” Smith said.

“You need the exuberance and the invincibility of youth to dare the status quo to change,” he added

On April 11, a week after King’s assassination, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which included the Fair Housing Act. On April 30, with seven newly elected members, the Common Council passed an even more comprehensive open housing ordinance by a vote of 15 to four.

It took another eight years for Barbee to win the federal case for school desegregation.

Although these laws brought improvements after more than a century of racial discrimination, 50 years later, Milwaukee remains one of the nation’s most segregated cities, in both housing and schools.

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on fifteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.

50 Years After The Marches

-

Pandemic Shines Spotlight on Workers’ Struggle

Sep 7th, 2020 by Erik Gunn

Sep 7th, 2020 by Erik Gunn

-

UW System Expects $212 million in Losses

![Van Hise Hall in the background. Photo by James Steakley (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://urbanmilwaukee.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/1017px-Ingraham_Van_Hise_carillon-185x122.jpg) May 8th, 2020 by Rich Kremer

May 8th, 2020 by Rich Kremer

-

51 of 72 Counties Now Back Fair Maps

Apr 15th, 2020 by Matt Rothschild

Apr 15th, 2020 by Matt Rothschild

“Although these laws brought improvements after more than a century of racial discrimination, 50 years later, Milwaukee remains one of the nation’s most segregated cities, in both housing and schools.”

Yeah, if only Milwaukee would get it’s act together. Maybe Milwaukee should look to its neighbors in Waukesha and Ozaukee county to see what type of integration they’ve built.

Excellent article by Andrea Waxman. Our family came to Milwaukee in the fall of 1969 and could not understand why there was such a “stay away from downtown” mentaliity. From the streets to the parks few people were outside during a beautiful fall. Our real estate agent. pushed for us to buy a house in the far suburbs, which did not appeal to us. After reading Andrea’s article, the 1960’s atmosphere in Milwaukee becomes painfully clear to me.

Over the years there have been some progress in integration but we have a long way to go to solve the segregation problems in Milwaukee. It is not helpful that education, employment and wages for African-Americans continue to be low.