How Zoning Can Grow Milwaukee

Why the city is shrinking. And how more duplexes, triplexes, townhomes and accessory dwellings could change this.

Lots of people want to live in Washington Heights—the Milwaukee neighborhood sandwiched between Washington Park to the east and Wauwatosa to the west. The median home price grew by $92,000 (53%) from 2019 to 2023, nearly double the citywide increase of $48,000. That’s based on my own analysis of arm’s length, single property Real Estate Transaction Returns file with the Wisconsin Department of Revenue. Meanwhile, average rents in the neighborhood grew by 16% in the past two years alone, double the national increase of 8%.

Despite this, Washington Heights is shrinking. The neighborhood’s population fell from 7,200 in 2000 to 6,741 in 2010 and 6,360 in 2020. That is a 12% drop in 20 years.

Imagine a typical block with 32 single-family homes (16 lots on each side of the street). In 2000, that block had 79 residents, which dropped to 76 in 2010, and 71 in 2020. Across many blocks, these small changes add up quickly.

Milwaukee’s lack of affordable, quality housing for low-income residents is a central focus among local policymakers, funders, and nonprofits. The situation in Washington Heights, a solidly middle-class neighborhood, points to a different but related dilemma. Even in neighborhoods where would-be residents can afford the cost to build new housing, adequate supply simply doesn’t exist, and current land use regulations inhibit its construction.

This lack of supply has cascading effects. Equity from rapidly increasing home values may please existing homeowners, but it also saddles them with higher property taxes. The long-term decline in the number of adult residents means fewer people are responsible for funding the same amount of infrastructure. People who are priced out of buying or renting in one neighborhood instead turn to a cheaper one, repeating the same pattern of displacement at a lower income bracket.

Washington Heights’ housing stock today is little changed from the early 20th century. Only six houses have been built in the neighborhood since 1960 (likely replacing older houses). Meanwhile, the net number of housing units has slowly shrunk. Since 1990, the neighborhood has lost 45 units thanks to duplexes being downgraded to single-family homes. And some triplexes being dropped to duplexes. Only three single-family homes have gone the other way, getting converted to duplexes.

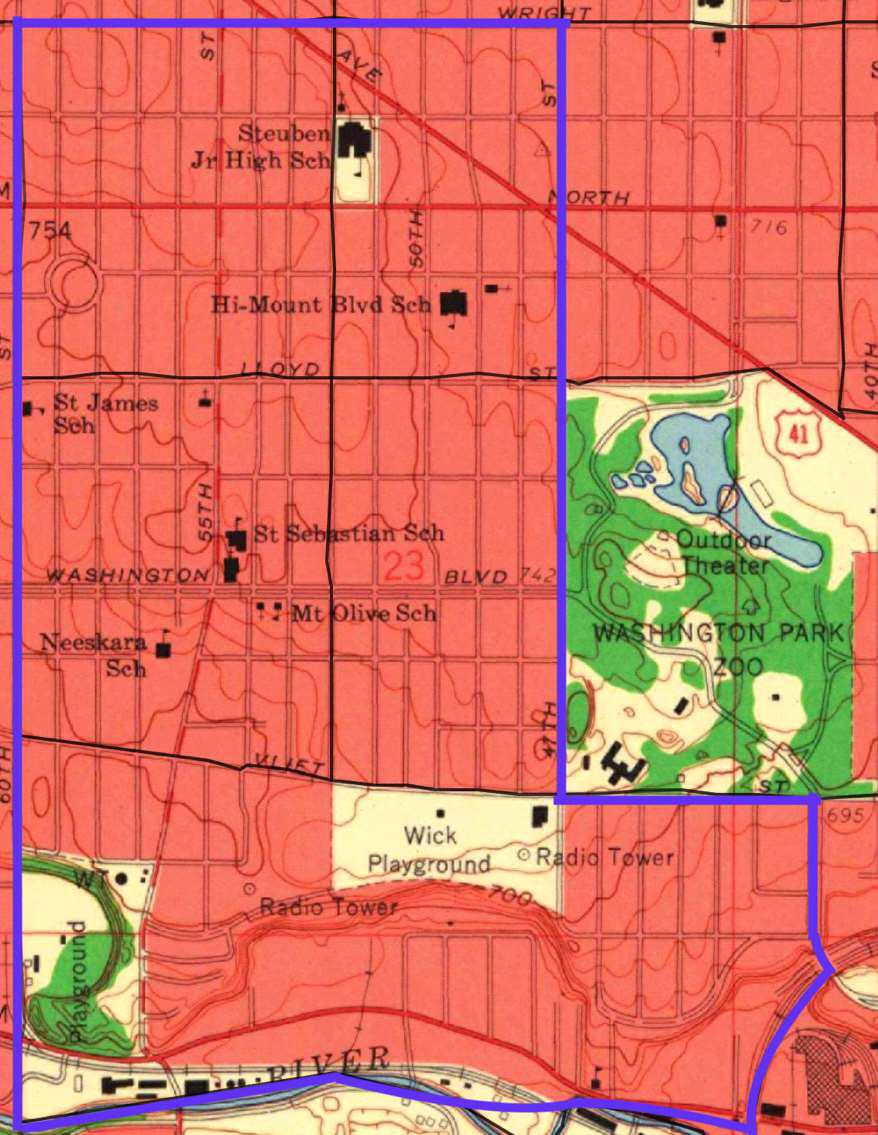

Consider the greater Washington Heights area, outlined in blue on the map below. (1960 tracts rarely exactly match current neighborhood boundaries.) This area had a 1960 population of 15,635 people living in households . That fell by 31%, to about 10,800 in 2020. The average household size fell from 2.9 to 2.2. The number of children declined by nearly 2,000 and the number of adults by 2,900. (All of these statistics are drawn from the City Assessor’s Master Property File.)

In other words, about 4,800 fewer people live within immediate walking distance of the historic commercial corridors along Vliet Street, North Avenue, and (at the time) Lloyd Street. And these commercial districts have changed too. Along Vliet, Lloyd, and North, just between 47th Street and 60th, there were 12 food stores in 1960 (including corner stores & butchers) along with seven bakeries, six pharmacies, 10 taverns, five restaurants, two hardware stores, and dozens of other retail stores or service providers (businesses are from the 1960 Milwaukee City Directory).

The number of restaurants along Vliet and North has more than doubled since 1960, and the number of taverns has held mostly steady. But other kinds of retail have vanished. No bakeries and only two food retailers remain. There are no hardware stores and only one small pharmacy.

The story of Washington Heights is common across Milwaukee. As I’ve previously written, about 40% of the city is in “stable decline,” characterized by high occupancy rates but shrinking populations due to declining household sizes.

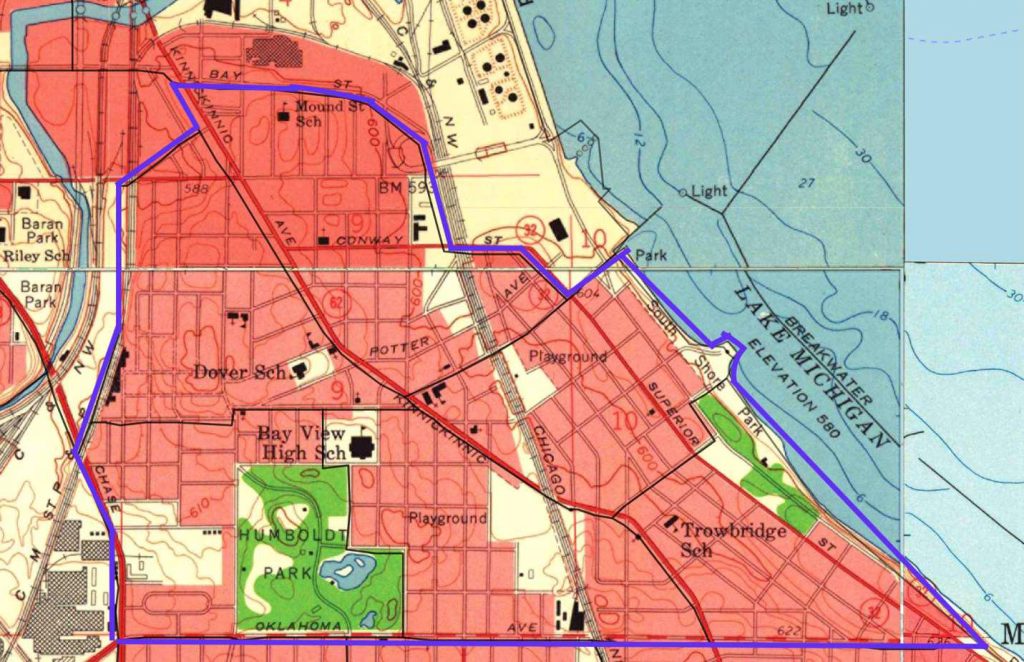

Consider the portion of Bay View north of Oklahoma Avenue. These tracts have lost 5,600 residents since 1960. It would take nearly 3,500 more housing units to restore the population of 60 years ago, given current household sizes. That is despite the fact that Bay View has built more housing. The number of units has grown by more than 700 since 1960. Without that, the neighborhood’s population would have plummeted by perhaps another 1,200 residents (This is a rough calculation, found by multiplying the number of net new units (715) by a typical occupancy rate (93%), then multiplying the product by Bay View’s current average household size of 1.97).

Some neighborhoods have built enough new housing to stave off the post-1960 housing collapse, and their historic commercial districts reflect that.

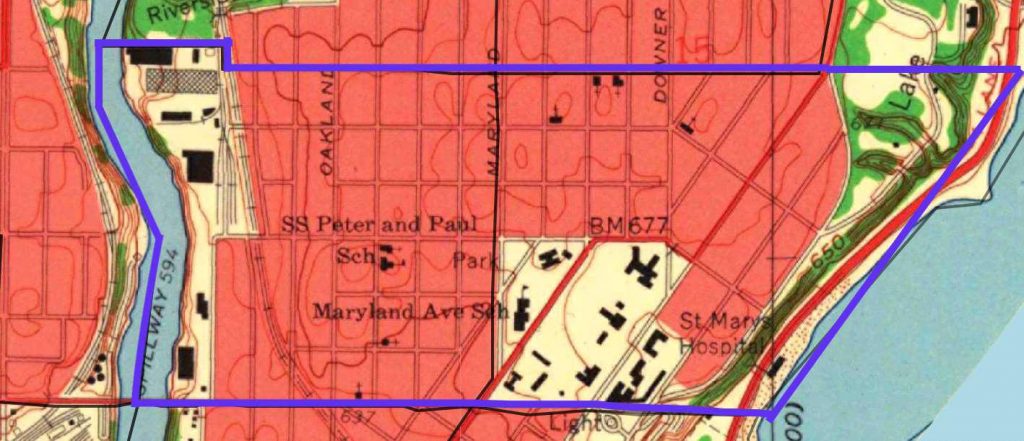

The two census tracts on the East Side between North Avenue and Park Place are good examples of this approach. Together, they have added 1,600 net new housing units since 1960. This has allowed the neighborhood’s overall population to remain steady despite the average household size falling. There has been a roughly 100 person decline (-2%) in the household population between 1960 and 2020, with the number of adults growing while the number of children fell.

Small wonder that the neighborhood has sustained a genuinely comprehensive commercial district. The area around Downer Avenue includes a full grocery store, a bakery, hardware store, pharmacy, dry cleaner, and multiple medical providers.

Much of Milwaukee’s East Side benefits from zoning rules that permit multi-family developments, whether apartment buildings or condos. Over 70% of the post-1960 construction in the two tracts near Downer Avenue occurred in parcels with high-density zoning classifications.

Other neighborhoods, like Walker’s Point and parts of Bay View, have successfully converted former industrial land and buildings into new housing. A current example is the redevelopment of the Filer and Stowell complex, which plans to build 576 new units across eight apartment buildings.

None of these kinds of construction are an option for neighborhoods like Washington Heights. Unlike the East Side, Washington Heights has no parcels zoned for high density development. Unlike Bay View or Downtown, Washington Heights was built as a purely residential neighborhood, so it doesn’t have legacy industrial sites or underused office buildings.

Washington Heights has also seen few home demolitions, so it mostly lacks the large (or adjacent) empty lots necessary to build townhomes. In short, there are few existing options for restoring the historic population density to neighborhoods like this.

The city’s new draft zoning reform plan, Growing MKE, proposes a set of changes to make growing the housing supply in places like Washington Heights more possible.

If adopted, the plan would change the kinds of housing which can be built under the city’s various residential zoning classes. All residential zones would permit the construction of single-family homes, accessory dwelling units, townhomes, duplexes, triplexes, and cottage courts. Those areas already zoned for duplexes (a substantial portion of the city) would also allow 3 and 4-unit buildings. Another provision would make it easier to build apartment buildings on lots already zoned for them.

Looking at the city as a whole, the most consequential aspects of Growing MKE are likely the provisions that encourage new multi-unit developments, from townhouses and cottage courts to quadplexes and small apartment buildings. These have the potential to grow the city’s housing stock the most.

These kinds of small backlot houses are common in Milwaukee’s older neighborhoods, where they are often called carriage houses. Other houses with large basements could be converted to include an “internal ADU.”

There are about 2,000 houses in Washington Heights. Half of their owners have held them for 8 years or more. Given the rapid increase in home values, many residents have accumulated significant equity in their homes, which could be used to finance ADU construction (ADU construction prices generally range from $60,000 to $225,000, according to data from Angi. Conversions are cheaper, new builds are more expensive.)

ADU construction tends to grow quickly in cities after the rules are changed to encourage them. Still, it’s not an overwhelming flood. In 2023, Seattle issued permits for 987 ADUs, up from 246 in 2018 (prior to reforms passed in 2019).

These numbers may seem low compared to the massive need for housing, but new construction is currently even more rare. Fewer than 150 single-family homes or duplexes were built in Milwaukee in the last four years combined (According to Milwaukee’s MPROP file).

What would it take for Washington Heights to stop shrinking? At the current pace, households are shrinking by about 0.1 persons per decade. Put differently, every 10 years, each 10 houses lose 1 resident. There are about 2,900 households in Washington Heights. At that pace of change, the neighborhood will lose about 290 more residents by 2030. Avoiding that loss would require building at least 140 more units, but probably more. (The figure of 140 assumes an unrealistic 100% occupancy rate and that the new housing units would have the same average household size as the existing housing stock.)

The zoning reforms proposed in the Growing MKE plan are intended to encourage property owners in the city to build more housing on their own. This will likely happen mainly in the parts of the city which are already relatively prosperous.

For the half of Milwaukee renters who spend more than 30% of their income on rent (and the quarter who spend 50% or more), market solutions alone are unlikely to build a sufficient quantity of actually affordable housing. But encouraging new housing construction in the parts of the city where the market will fund it is a crucial way for the city to create more options for property owners and renters alike, while also expanding its tax base.

By allowing the market to build housing in places where existing demand will pay for it, the city can better steer its resources toward subsidizing housing development in the neighborhoods of Milwaukee where the need is dire but the market will not provide it.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

When the 1950 Census data was released a few years ago, I looked for (and eventually found) where my parents lived before I was born. What was astounding was how big most families were back then. It seemed like families of 5 or 6 were quite common.

Extremely insightful article. Just the facts. Either we have a housing crisis or we don’t. And if we do, we cannot be hamstringing market solutions where market solutions will have a positive impact. Allow more housing

ADUs aren’t a real solution in Washington Heights since most lots are not large enough for a second structure. The best option I’ve seen to increase housing units in the neighborhood is the plan to reduce 175 & build mixed use retail/residential on a new boulevard replacing that dead end highway.

Typical external ADUs have about the same footprint as a two-car garage. Most lots in Washington Heights have such a garage, so there is plenty of room on an average lot for an accessory dwelling unit.

John, while there are homes that have 2 car garages they often are already duplex properties. As an example, most every home within several blocks on my street has only a 1car garage. Parking would also need to be addressed, as it’s unlikely most people would trade car ownership for population density without access to the walkable business district of the past that you referenced.

It would be great if this were the case & we could add units.

I’d like to see a more detailed assessment of the % of properties that are actual candidates for ADUs.

Great, informative analysis. Thank you!

I grew up on 56th just south of Lloyd in a duplex w/a two car garage.

We lived on the first floor – 4 kids and 2 parents in 3 bedrooms. Upstairs was 2 bedrooms .

In the 50’s each unit had one car. As the 60’s rolled in we had 3 cars (dad’s, mom’s and my brothers “beater”. Eventually I also had a car – 4 cars for one unit). Upstairs still had one car.

5 cars for one house and one 2 car garage. Parking restrictions got stricter – the street is narrow. Gradually we kids moved out which helped.

There is no way that another building could have been built in the back yard as one bedroom was an addition which chewed up backyard space.

Also – – another car?????

I appreciate the idea, but I do agree that the best answer is to replace hgy 175

It is a great neighborhood and perhaps a few houses have the space and the willingness to build. Room for cars is an issue.