Local Groups Promote Equitable Water Access and Recreation

An ever-growing variety of groups and activities enjoy Milwaukee's waters.

Models wearing Native Nations designs of Sabrina Lombardo walk the runway during Indigenous Elegance at Harbor View Plaza on June 14, 2024. Sponsored by a grant by Joy Engine and organized by the nonprofit Harbor District, Inc., it was the first ever fashion runway event by the water anywhere in Milwaukee. Photo by Michael Timm.

For Father’s Day a few years ago, Nora Godoy-González treated her parents to a Duffy Boat pontoon ride on the Milwaukee River. Though Milwaukeeans since the early 1990s, it was their first time on a boat here.

“We were listening to all the Mexican corridos on blast — all the while people staring at us,” Godoy-González said with a laugh. “Drinking our chelas — it was such a beautiful moment and I’ll never forget it.”

As a first-generation daughter of immigrants from Central Mexico, Godoy-González brings a personal passion for connecting people to the water in her job as placemaking director at the nonprofit Harbor District, Inc.

Harbor District is among a bevy of groups working to welcome more Milwaukeeans of all colors, languages, cultures, ages, and identities to the water.

Indigenous Elegance, a fashion show at Harbor View Plaza held June 14 — Milwaukee’s first outdoor runway event anywhere along the water — is just one example.

Featuring models wearing the Native Nation Designs couture of Sabrina Lombardo — a proud member of the Tarahumara and Tigua tribes and first graduate of the Edessa School of Fashion — the free event also included local Indigenous craft and food vendors.

Godoy-González also organizes Summer en la Plaza at Harbor View Plaza, 600 E. Greenfield Ave. — free activities ranging from dance to drumming, painting, and poetry.

“I think the biggest thing is people being able to see themselves in these spaces,” Godoy-González said. “That authenticity piece has to be there in order for spaces like Harbor View Plaza and the lakefront to be really enjoyed by people of color — people who have been here for generations.”

Kayaking is another opportunity to draw diverse demographics to the water. Partnering with Milwaukee Kayak Company, Harbor District hosted bilingual kayak tours starting from Harbor View Plaza’s accessible launch.

Beth Handle has owned and operated Milwaukee Kayak Company for 12 years. She’s witnessed a major increase in people on the water over that span — plus a wave of more diverse boaters since the pandemic. Handle started her business with just 12 kayaks. Now it has dozens. “I don’t remember it ever being as busy as it is right now,” Handle said.

Beyond individual outings, going kayaking in Milwaukee has become a summer social activity coupled with waterside beverages and entertainment.

Every Wednesday evening, the “Milwaukee River Roundup” features a veritable flotilla of Handle’s kayaks paddling from Twisted Fisherman on the Menomonee River up to The Harp on the Milwaukee River. On June 12, some 70 paddlecraft schooled together following the “Funktoon,” a pontoon boat that features a different live band every week.

About 70 paddlecraft followed the Funktoon during the Milwaukee River Roundup sponsored by Milwaukee Kayak Company with support from Joy Engine on June 12, 2024. View is south from St. Paul Street Bridge. Photo by Michael Timm.

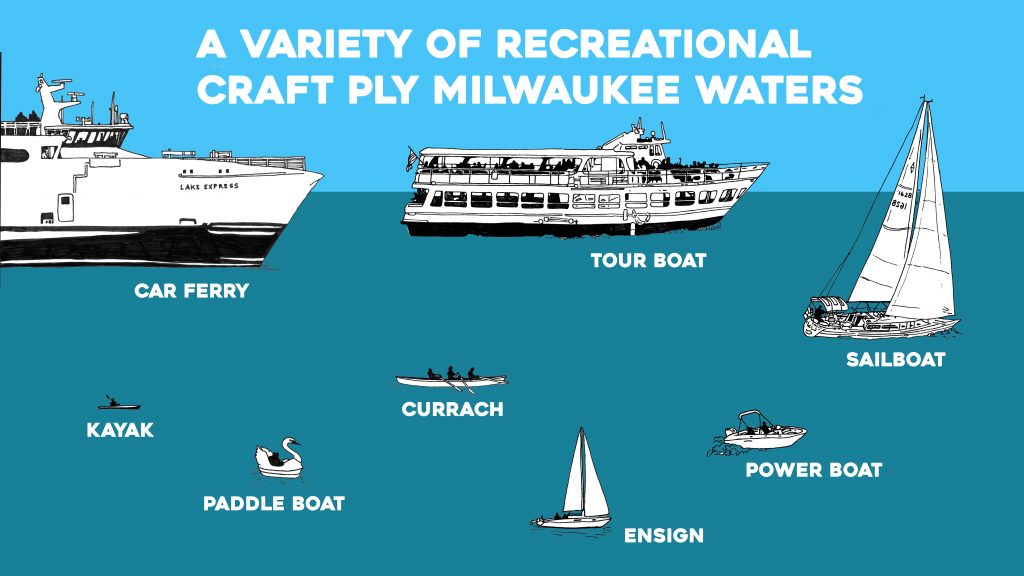

As an increasing variety of recreational boats ply Milwaukee’s summer waters — kayaks, fishing boats, jet skis, rowing crews, pontoon boats, sailboats, dinner boats, and now even cruise ships — crowding and boater awareness sometimes lead to tension on the waves.

Kristen Scheuing, president of the Irish Currach Club of Milwaukee, has been rowing the club’s currachs — traditional canvas-bottom boats rowed by a team using bladeless oars — since 1999. She prefers to avoid the Milwaukee River and row the open waters of Lake Michigan.

Some powered boats fail to observe the five-knot no-wake limit inside the breakwater, Scheuing said, recounting multiple close calls including an incident when their boat was targeted with spray by jet skiers.

Vessels common to Milwaukee’s lakefront and harbor are drawn to relative scale. The harbor has grown more densely used by recreational vessels in recent years. Illustration by Sarah Gail Luther.

“The boat traffic is crazy,” Scheuing said. “I mean, if Vista King doesn’t know how to maneuver around me, I know for sure a pedal tavern isn’t going to, or the pirate boat, or any of those booze cruises.”

At the same time, getting more people comfortable on the water — especially young people in human-powered boats — is part of their club’s mission.

For the past four summers Milwaukee Currach has partnered with fellow nonprofit All Hands Boatworks to get kids out on the water in boats that youth make themselves. They launch from the Emmber Lane public boat ramp, an Urban Water Trail access point near where All Hands Boatworks has a small boatyard.

All Hands Boatworks, based out of an industrial building near 12th and Bruce Street, runs other boat-building projects for youth. Patrick McBriarty manages the group’s new 15-week On the Water internship program, started in spring 2024 to connect urban youth with maritime career opportunities.

McBriarty grew up hanging out at yacht clubs, and wants to share his passion for boating with the next generation. “It’s something that if you have access to it, you forget how difficult it is to get in,” he said.

The program included sessions with Coast Guard, Milwaukee Fire Department, and crews working aboard Milwaukee dinner and sightseeing boats, plus an online boating safety certification course.

Interns overcame fears of water and explored new interests.

Evaija Hubbart, 14, never had swimming lessons. For Hubbart, paddling with McBriarty on the Menomonee River was her first time in a canoe. A water safety course required the interns to get in a pool fully clothed wearing a life jacket to face what it would feel like overboard. From braving these experiences, “I’m way less nervous than I was before,” Hubbart said with a smile.

Manrique Valladares, 15, who had never been into boats, grew into a leadership role. He got interested in carpentry and appreciates the internship as something he enjoys, earns him money, and helps other people. “It’s a win-win-win,” he said beside proud parents on May 22, when All Hands Boatworks launched a rowboat the interns worked together to build — christened the Green Heron — at the Milwaukee Community Sailing Center.

Manrique Valladares, 15, with his mom and dad at the Milwaukee Community Sailing Center on May 22, 2024. Valladares was an intern with All Hands Boatworks. Photo by Michael Timm.

The nonprofit sailing center’s Teresa Coronado pointed to Wisconsin’s Public Trust Doctrine — part of the state constitution ensuring public access to the state’s waters, including filled lakebed land like where the nonprofit has a 50-year lease with Milwaukee County Parks — as a point of pride allowing for these types of activities.

When she goes to community centers to share programming or promote water access, Coronado said she always starts by sharing her Mexican American identity and understanding of generational trauma around water.

It’s a trauma that goes back to grandparents and parents who remember not being able to go to a pool because of discrimination against people who were Black or brown, Coronado said.

As Milwaukee County faces funding challenges, the sailing center is working with other groups to increase water comfort and safety for all.

Milwaukee Parks Foundation sponsors the Aquatic Ambassadors program to encourage people of color to become summer lifeguards with Milwaukee County Parks. In 2024, six Aquatic Ambassadors shared personal water stories on the group’s website.

Milwaukee Water Commons, Milwaukee Riverkeeper, and UW-Sea Grant sponsor a Beach Ambassadors program, employing summer workers to educate beachgoers about water safety resources so they can make informed decisions about whether to swim.

Safety efforts complement physical infrastructure to accommodate people of differing abilities. In 2020, Bradford Beach was heralded as the country’s most accessible beach when it installed a blue Mobi Mat atop a concrete path and four beach-accessible wheelchairs, supported by the Ability Center.

Promoting equitable water access also means making residents aware of publicly accessible urban natural areas where water flows — “green and blue spaces.”

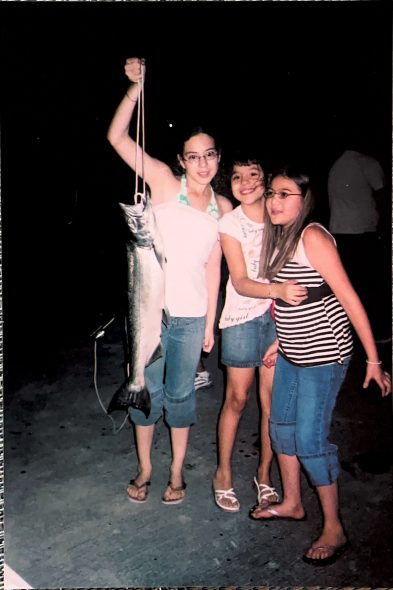

An older fisherman let young Elsa Godoy, Nora Godoy-González (center), and Deisy Godoy hold this fish during the girls’ visit to Milwaukee’s McKinley fishing pier in 2005 or 2006. Visiting Lake Michigan as a young girl was transformative for Nora Godoy-González, who now works as placemaking director for the nonprofit Harbor District, Inc. in a role that welcomes people of all backgrounds to the water. Photo courtesy Nora Godoy-González.

On June 15, the nonprofit Nearby Nature hosted its Lincoln Creek Celebration at Havenwoods — Wisconsin’s only urban state forest and free to the public. The creek flows through Havenwoods, where long-term habitat enhancement projects to woodland, prairie, and wetland are planned as part of larger efforts to rehabilitate the Milwaukee Estuary Area of Concern.

At the event, Nearby Nature speakers also highlighted Hopkins Hollow, 19 acres near 35th and Hopkins several miles downstream along Lincoln Creek. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) has worked with the group as well as UW-Milwaukee students to document wildlife here — including deer, coyote, dozens of bird species, bats, turtles, and the Butler’s garter snake. Not to mention fish.

Fishing is another way Milwaukeeans of all colors share an intergenerational love of water’s wonder.

For the past three years, Joseph Addison, with the group 100 Black Men for Milwaukee, has run free fishing clinics at Lakeshore State Park, partnering with WDNR to attract young people to the activity. One is planned for Sept. 7. “Fishing has no barrier,” Addison said.

Equity advocates hope the positive memories made gathering by the water — fishing, boating, or just being in nature — last a lifetime.

Some already have.

Godoy-González still recalls the first time she went down to Lake Michigan as a little girl. Her cousin took her to Bradford Beach for an ice cream. She felt she’d been transported from her Walker’s Point neighborhood into a whole new world.

“I was just sitting there eating my ice cream in awe,” she said. “And I was like, wow, this is amazing. And I think that was the first time I truly felt connected to Lake Michigan.”

Photos by Michael Timm

Photos

Writer Michael Timm, a Milwaukee Water Storyteller for the nonprofit Reflo, did our earlier series on reintroducing the sturgeon into the Milwaukee River.

This project is funded by the Wisconsin Department of Administration, Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the terms and conditions of Wisconsin Coastal Management Program Grant Agreement No. AD239125-024.21. Funded by the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office for Coastal Management under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant # NA22NOS4190085

Wow!! Awesome!! Wish this was available in the 1970s & 1980s!!