How Salt Is Polluting State’s Waters

Rising levels of sodium and chloride can harm all species, and threaten humans. Part 2 of a series.

Dr. Hilary Dugan, a scientist at the University of Wisconsin Center for Limnology at Madison, stands by a salt pile in the Jefferson County Salt Barn in February 2019. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Salt Wise.

When salt dissolves into water as ions of sodium and chloride it does not disappear.

Dr. Hilary Dugan, a scientist at the University of Wisconsin Center for Limnology at Madison, is among a chorus raising the alarm about chloride pollution to Wisconsin waters.

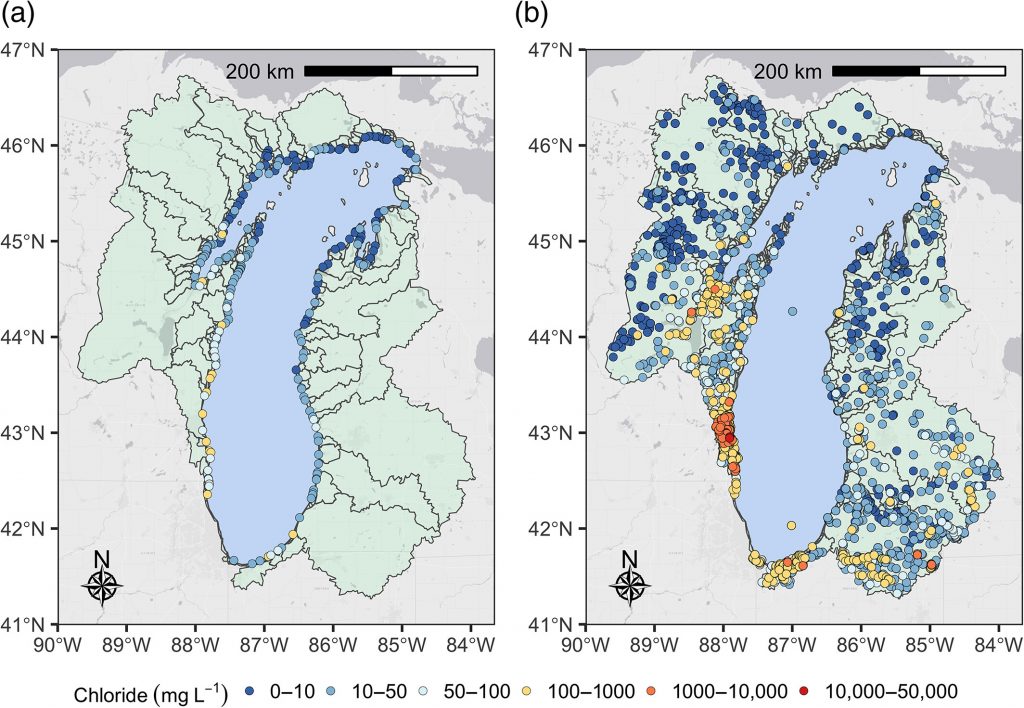

Dugan’s research estimates that about 1.2 million tons of chloride enter Lake Michigan via its tributaries every year—slowly but measurably raising the salinity of our freshwater lake.

An overview of salt sources, pathways, and impacts for Milwaukee and our waters based on SEWRPC chloride impact reports and independent research, 2024. For printable one-pagers, visit https://refloh2o.com/water-stories. Illustration by Sarah Gail Luther.

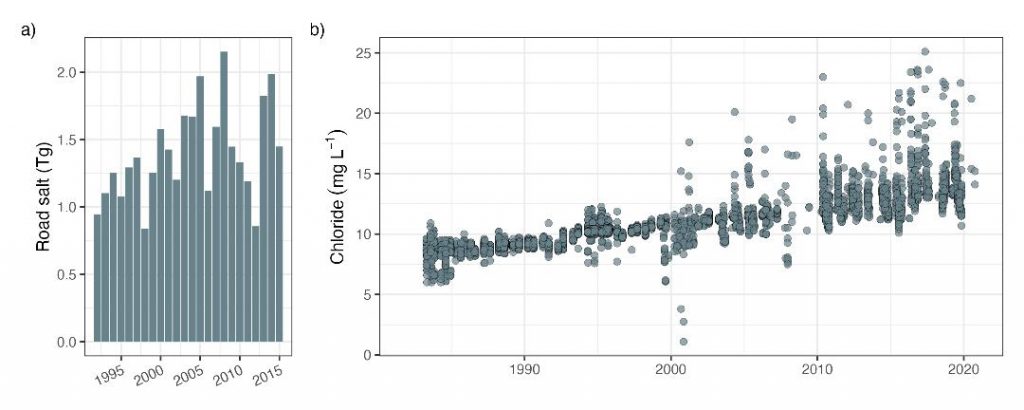

Chloride concentrations in the Great Lakes have risen from 1-2 milligrams per liter in the 1800s to contemporary concentrations greater than 10, Dugan and her co-authors reported in a 2021 paper. From 1980 to 2020, Lake Michigan chloride concentrations rose from about 9 to 15 milligrams per liter.

They identified urbanized, highly impervious watersheds as closely correlated with salt loading.

“The largest of these highly urbanized tributaries is the Milwaukee River, which accounts for approximately 8% of the total tributary load (5th largest contributor overall),” Dugan and her fellow authors wrote.

Lake Michigan is actually getting saltier from human contributions to rivers and streams in the watershed. The figure above includes concentration data from the 2021 Limnology and Oceanography Letters paper, “Tributary chloride loading into Lake Michigan” whose lead author was Dr. Hilary Dugan. Prior to the 1990s, chloride concentrations were routinely below 10 milligrams per liter. Recent concentrations are closer to 15 milligrams per liter. Estimated mass inputs of road salt in the Lake Michigan watershed are shown left per year. One teragram is 1 million metric tons. One metric ton is 1,000 kilograms. Reproduced with the author’s permission.

Our freshwater, the source of public drinking water supplies, is getting saltier due to human activity.

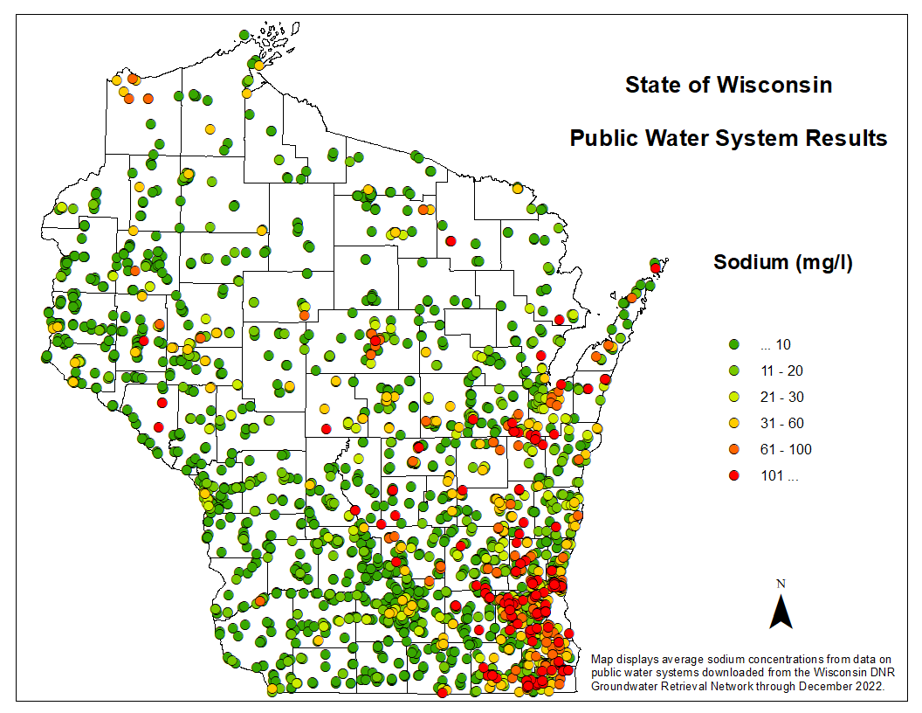

During a January 31, 2024 meeting of the Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission Chloride Impact Study Technical Advisory Committee, SEWRPC’s principal planner Joe Boxhorn noted that the U.S. EPA recommends 20 milligrams per liter as the upper limit of sodium in drinking water for health purposes. “I would note that based on their consumer confidence reports, 34 municipal water utilities in the region report sodium concentrations higher than this,” Boxhorn said. “So, it is a problem.”

Milwaukee’s drinking water measures below that threshold for now. The 2022 Milwaukee Water Works consumer confidence report notes an average chloride concentration of 15.5 milligrams per liter and 9.95 milligrams per liter of sodium. The 2016 value for chloride was 14.5 milligrams per liter.

Increases in chloride concentration in drinking water can promote corrosion of plumbing, which can release metals such as lead, Boxhorn noted. As for sodium, elevated levels in drinking water can raise blood pressure risks. Even airborne micro-particulate de-icing salts can contribute to statistically subtle human health impacts for lung diseases.

This map displays average sodium concentrations from data on public water systems downloaded from the Wisconsin DNR Groundwater Retrieval Network through December 2022. Courtesy of Wisconsin Salt Wise.

More directly concerning are the toxicity of chloride to aquatic life and disruption to food webs.

The nonprofit organization Milwaukee Riverkeeper puts the case clearly on its website: “Road Salt is a threat to our waterways. Chloride, the key element in road salts, poses a threat to the health of our rivers and environment. When water runs over the landscape, it picks up pollutants along the way, including excess road salt and other deicing chemicals. These contaminants pollute our rivers, streams and lakes. If used correctly, road salt can be a helpful safety precaution. When we use too much, we damage our roads and environment, while not increasing safety.”

A view of salt piles on Port Milwaukee parcels leased by Compass Minerals looking north from the Lincoln Avenue Viaduct in January 2024. Photo by Michael Timm.

Under Section 303(d) of the U.S. Clean Water Act, states identify impaired waters to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. In Wisconsin, the current water quality criteria for chloride toxicity is 395 milligrams per liter (chronic) and 757 milligrams per liter (acute).

Since 2010 Milwaukee Riverkeeper has measured chloride concentrations in local waterways, launching its Winter Road Salt Monitoring program supported by volunteers in 2011. Their monitoring has helped provide the state with data showing when chloride levels exceed state criteria.

“Of the Milwaukee River Basin’s 500 miles of perennial streams,” Riverkeeper notes, “117 miles are listed as impaired for chloride pollution” on the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources’ Listed Impairments for 2022.

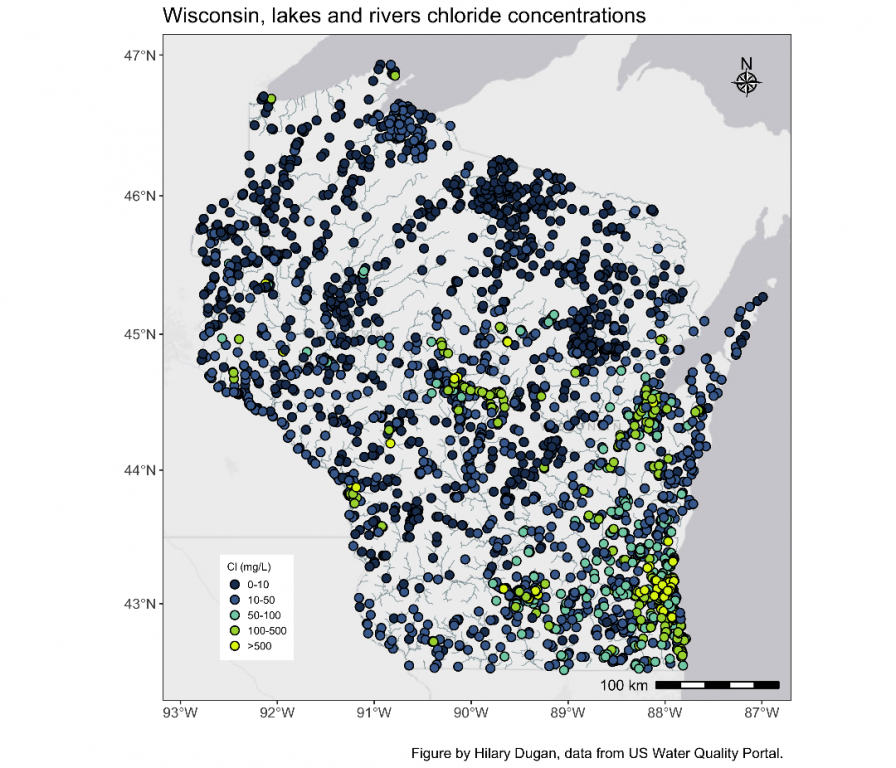

The maps above include tributary chloride concentration data from the 2021 Limnology and Oceanography Letters paper, “Tributary chloride loading into Lake Michigan” whose lead author was Dr. Hilary Dugan. The left map shows values measured for one week in July 2018. The right map show values from many years and sources. The highest concentrations of chloride are clustered in the Milwaukee-area tributaries to Lake Michigan with other urban watersheds also contributing more chloride than less urban ones. Reproduced with the author’s permission.

Chloride impacts are growing in recent years.

“More than half of the existing impaired waters listings for chloride were added in the 2016 and 2018 reporting cycles and are located in the Milwaukee area,” according to a December 2022 Wisconsin chlorides workgroup report to the state’s Water Initiatives Steering Committee.

Amid rising concerns, in 2017 SEWRPC embarked on a detailed review and analysis of chloride impacts consisting of two years of its own field data collection and a years-long process of releasing seven technical reports.

Mean chloride concentrations in Wisconsin lakes and rivers. Figure by Hilary Dugan, data from US Water Quality Portal. Courtesy of Wisconsin Salt Wise.

It can be hard to think of salt as a dangerous pollutant because we routinely consume it, but excessive chloride can harm organisms through a variety of ways—especially those with life cycles immersed in water. Too much salt can outright kill sensitive organisms, but even non-lethal concentrations can affect growth and development and reverberate through food webs.

Boxhorn’s Jan. 31, 2024 presentation summarizing the findings of his 175-page report read like a litany of abuses implicating excessive chloride.

In a striking example, Boxhorn showed a photo of two fishes from a University of Toledo experiment published in 2017 that compared rainbow trout exposed to 25 days of different concentrations of de-icing salts.

The fish above was exposed to 25 days of 3,000 milligrams per liter of calcium chloride. The fish below was part of a control group not exposed to chloride. The experiment found similar growth reduction impacts for fishes also exposed to 3,000 milligrams per liter of sodium chloride. Calcium and sodium chloride are both used as road salt. The research, published by William Hintz and Rick Relyea in a 2017 issue of Environmental Pollution, considered different types and concentrations of chloride salts on the development of young rainbow trout. Photo by Bill Hintz.

The fish grown in water exposed to the highest chloride concentrations was stunted compared to its control counterpart grown in salt-free water. The photo makes plain what can be hard to visualize about salt’s impact on many other freshwater organisms and communities with a range of salt tolerances.

One way excessive chloride harms aquatic organisms is through “osmotic stress” where cells are forced to divert energy from other processes to pump out chloride ions. That’s energy that would otherwise be used for growth, reproduction, feeding, or protection.

Essentially, organisms suffering from “osmotic stress” become impoverished.

Boxhorn’s review of scientific literature also raised the question whether current water quality criteria designed to be protective of the environment account for subtler impacts on the structure of aquatic communities. Boxhorn identified at least nine studies that observed community-level changes at chloride concentrations below Wisconsin’s water quality criteria.

One of those was conducted by Dr. William Hintz, whose University of Toledo lab did the earlier rainbow trout study.

“The vast majority of research contributing to our understanding of salt pollution has been conducted in laboratory settings under ‘perfect’ conditions with the ‘lab rats’ of science,” Hintz said in an email. “However, when we use semi-natural mesocosm experiments that contain a greater diversity of species and species interactions, we find that the impacts of salt pollution can occur at lower concentrations than previously thought.

“Ultimately, science can be slow to catch up with environmental change or issues like salt pollution,” Hintz said. “We certainly need to understand how salt pollution affects a greater diversity of freshwater species and ecosystem processes, but the available evidence suggests we should act sooner rather than later.”

At least 34 river and stream reaches in southeastern Wisconsin were listed as impaired by chloride in 2022, according to SEWRPC. That includes over 24 miles of the Menomonee River, over 30 miles of the Root River, 13 miles of Oak Creek, the entire Kinnickinnic River, and river miles of other urban waterways including the Honey, Indian, and Lincoln creeks. More waterways are likely impacted but go unmonitored.

Over a decade of Riverkeeper monitoring has revealed now-common spikes in chloride indicators following snowmelt or runoff events in winter or spring.

“We’re seeing more spikes in the summer, which is concerning,” observed Milwaukee Riverkeeper’s Cheryl Nenn during the Jan. 31, 2024 TAC meeting. “And, I mean, not shockingly in a lot of the urban creeks that are draining the highway, but even in some of the other creeks, we’ve been seeing exceedences now in the summer.”

This appears to be due to salty groundwater, according to Dr. C.J. “Charlie” Paradis, UW-Milwaukee assistant professor of geosciences, who has proposed studying the Milwaukee River to better understand the fate and transport of salts in and out of freshwater streams.

“The annual persistence of salts is commonly attributed to groundwater and movement via baseflow to streams,” Paradis wrote. “However, salts may also be stored above the groundwater table and moved via stormflow streams.”

While scientists continue to study how the “The Freshwater Salinization Syndrome” impacts the web of life, the source of the problem is clear.

It’s us.

This is the second story in a series by Michael Timm, a Milwaukee Water Storyteller for the nonprofit Reflo, who did our earlier series on reintroducing the sturgeon into the Milwaukee River. He holds a 2013 master’s degree in freshwater science from UW-Milwaukee. He previously wrote and edited for the Bay View Compass newspaper.

This project is funded by the Wisconsin Department of Administration, Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the terms and conditions of Wisconsin Coastal Management Program Grant Agreement No. AD239125-024.21. Funded by the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office for Coastal Management under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant # NA22NOS4190085

Water Series

-

Why Do We Care About The Sturgeon?

Feb 15th, 2024 by Michael Timm

Feb 15th, 2024 by Michael Timm

-

The Return of the Sturgeon

Jan 31st, 2024 by Michael Timm

Jan 31st, 2024 by Michael Timm

-

How the Kletzsch Fishway Was Created

Jan 19th, 2024 by Michael Timm

Jan 19th, 2024 by Michael Timm

Thx for this analysis; am hopeful it has impact in the coming winters, Michael Timm