Why Do We Care About The Sturgeon?

How reintroducing sturgeon to the Milwaukee River connects all of us. Third story in series.

Members of the Sturgeon Protectors group meets at the UW-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences on Feb. 1, 2024. From left to right: Anne Steinberg, Eric Hansen, Mark Denning, Shirley Aspinall, Don Behm, David Wenstrup, Clare Eigenbrode, and Cheryl Nenn. Photo by Michael Timm.

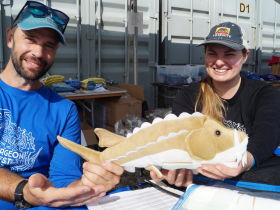

Plush sturgeon toys. Foam sturgeon puppets. Vibrant sturgeon murals at Sturgeon Fest.

For a growing number of Milwaukeeans, the lake sturgeon has become a potent symbol of a new relationship with water: Hope on fins.

From curious children petting them in a touch tank at Discovery World to annually hand-releasing hundreds of bony-backed fish from ice cream buckets into Milwaukee waters, sturgeon have recaptured the public imagination.

Why?

“Why do we care?” asked Nicholas Miller, pursuing his PhD in Multispecies History and Anthropology at UW-Milwaukee in fall 2023. “Why are we putting so much energy into restoring these? They were here before and we’re trying to repopulate them. Why is that important to people?”

Miller (no relation to Ozaukee County’s Ryan Miller, who mapped prospective sturgeon spawning habitat), attended Harbor Fest on Sept. 24, 2023 to find out.

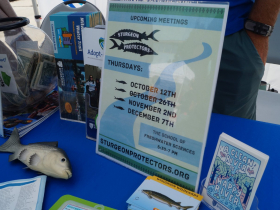

Since 2021, the annual street festival on E. Greenfield Avenue, run by the nonprofit Harbor District, Inc., has also incorporated Sturgeon Fest, an annual celebration supported by the nonprofit Riveredge and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). The partners rear young sturgeon that the public are invited to release into the water in support of a 25-year effort to reintroduce a self-sustaining population.

It’s a fitting location. The WDNR Lake Michigan southern fisheries division is headquartered in the adjacent Great Lakes Research Facility managed by the UW-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences. The harbor slip and homeport of the EPA Lake Guardian and R/V Neeskay research vessels offers a protected sturgeon release point connected to Milwaukee’s Inner Harbor. And Harbor Fest offers a family-friendly destination welcoming nearby Latinx neighborhoods to the water’s edge at Harbor View Plaza.

Among the pungent aromas effused from food trucks, colorful performances of public artists, and tabling displays of water-related organizations, Miller circulated among the crowd, speaking to sturgeon advocates to inform his research.

“It’s just another sign the river is becoming more healthy,” Anne Steinberg told him of the sturgeon returning. “It helps people feel connected to our watersheds.”

Steinberg is part of a volunteer group inspired by the efforts of the “Sturgeon Guard” who station themselves along the banks of the Wolf River during spring spawning runs to protect these giant fish from poaching.

In Milwaukee, these “Sturgeon Protectors” are focused on public education. The Native American-led citizen’s group shared a table with Milwaukee Riverkeeper at Harbor Fest.

“After 20 years of reintroduction efforts, lake sturgeon are finally making a comeback to the Milwaukee River, which is so exciting,” said Cheryl Nenn, riverkeeper with Milwaukee Riverkeeper, who is helping organize the Sturgeon Protectors. “In the last few years, there have been several documented and rumored poaching incidents of these prehistoric fish—which is concerning given the extraordinary efforts of so many—and also because it can take sturgeon 20 years to reach reproductive maturity! So, to have them poached, either knowingly or unknowingly, as they return to our river to spawn, is heartbreaking.”

The heart of the Milwaukee Sturgeon Protectors is Mark Denning, a member of Sturgeon Clan enrolled in the Oneida Tribe of Wisconsin, whose ancestry includes Menominee, Mille Lacs Ojibwe, Stockbridge-Munsee, French, and English.

Mark Denning, a member of Sturgeon Clan enrolled in the Oneida Tribe of Wisconsin, is the heart of the Sturgeon Protectors people’s group. Photo by Michael Timm.

“When Sturgeon return home, we should be thinking about what kind of home that place will be,” Denning wrote. “Like us, as Native people, sturgeon had been removed from their original homelands. We, as they, have seen in this place displacement, destruction, and disease. Barriers kept us, and them, from returning home. Whatever vestiges remained from the devastation, our ancestors survived—quietly, waiting, watching mostly invisible living on the edges of what we once called home. We, as Natives, have returned, in some cases never left… So now our relatives are able to return—but return to what?”

Milwaukee’s Sturgeon Protectors are organizing to make that return a warm welcome.

At their Feb. 1, 2024 meeting inside the UW-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences, the group received a briefing from WDNR’s fisheries biologist Aaron Schiller, who advised when and where sturgeon have been observed in the Milwaukee River. This can help the volunteers prepare for spring, when rising flows and water temperatures are expected to coincide with sturgeon pushing upriver.

Denning showcased Sturgeon Protectors artwork designed by Milwaukee artist Sue Bietila that can be printed on shirts or kerchiefs to identify volunteers. Come spring, Sturgeon Protectors will plan volunteer patrols, likely in Estabrook and Kletzsch parks, to teach the public about this fish and remind anglers it is illegal to fish for the protected species.

Freelance writer Clare Eigenbrode shared draft content for the group’s website, sturgeonprotectors.org. Retired Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reporter and Wisconsin’s Green Fire board secretary Don Behm shared his historical research seeking the last documented sturgeon in the Milwaukee River prior to extirpation. Riverkeeper Nenn reported on an application for a Wisconsin Coastal Management Program grant to support activities into next year.

Denning also suggested two possible Indigenous-led activities for spring 2024 along the Milwaukee River: a water walk led by tribal elders and setting up traditional teaching lodge. “A lot of guys are saying it’s something they want to do with their sons,” Denning said. “And our women warriors want to do it with their daughters.”

It’s intentional, intergenerational work aimed at interspecies—and internal—healing.

“As Sturgeon struggle to get home after over a century and decades of banishment, we should be working and create inside of each of us a work ethic that whatever we can do to ease that return, we must do,” Denning wrote. “Is this not what we do for the victims of war?

“We, as Native people, stand as relatives to Sturgeon and in our bond we both understand blood memory, an ancestral and genetic call that transcends time. Land and Water share this memory too. Imagine what it must be like when each meets in healthy, grounded places of abundance. That is what must continue to happen,” Denning wrote. “As they live, we live.”

Denning’s words have become the Sturgeon Protectors’ slogan and help to answer PhD student Miller’s fundamental question.

Consulting historic maps of the Milwaukee River, along with its former tributaries and wetlands, drawn from the public land surveys of 1835-1837, reveal how much the geography of our land and waters have changed over the past 200 years after the 1833 Treaty of Chicago pushed many Native Americans from ancestral lands and paved the way for widespread white settlement.

As we’ve lived more intensively—damming rivers, removing trees, concentrating wastes, paving our surroundings—various they’s haven’t always prospered.

About 20 years ago, the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD) added a great blue heron to its logo. The addition was both aspirational and prophetic—a visible symbol standing for invisible water quality.

Once unthinkable for some river reaches, if you travel the length of the Milwaukee River in the 2020s, an increasing diversity of bird life is evident as you head upstream.

Scissoring swallows roost beneath the bascule bridges of downtown Milwaukee, redwing blackbirds dive-bomb the banks at the River Revitalization Foundation’s Turtle Park by the former North Avenue Dam, hawks circle among myriad species spotted along the riverbank trails at Riverside Urban Ecology Center, great blue herons squawk in the rocky shallows at Estabrook Falls, egrets flash their wings in sunlit circles by the Mequon-Thiensville fishway, while kingfishers and green herons wing their ways above the sarsaparilla waters of the Milwaukee River at Riveredge Nature Center.

We share the same river.

Birds eat fish. Healthy birds mean healthy fish. Healthy fish mean healthy water.

While the aquatic food web is not quite that simple, the general equation holds.

And the lesson is being learned.

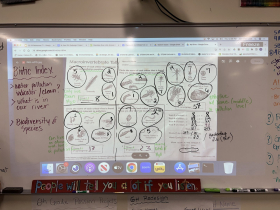

Seventh graders sampled the water’s turbidity and tested for pH, dissolved oxygen, nitrate, and phosphate. They also measured the river speed, temperature, and assessed an Index of Biological Integrity based on what organisms they observed. Photo by Michael Timm.

At Kletzsch Park, as seventh grader Elijah “Eli” Pacada put it, “We’re seeing if our waters are clean or not by looking at which animals are in there.”

In fall 2023, Pacada was at Kletzsch Park with his seventh grade class from Glen Hills Middle School. The seventh graders left their shoes on shore, pulling on hip waders to venture into the river itself. They measured the water’s temperature, speed, and pH. They turned over rocks to uncover invertebrates. Among their finds: damselfly larvae, stonefly nymphs, dragonfly larvae, crayfish and water pennies.

Pacada had never seen a sturgeon, but said he would like to. His main question about the water: “If it’s safe for living things?”

Lalitha Murali, Pacada’s teacher, said many kids in her class come to Kletzsch Park to fish but others know little about the fishway, the dam or the river itself.

“We want to teach them because it’s in our backyard,” Murali said. “Many kids, they don’t understand that it’s such a precious natural resource in their backyard, and how they need to understand and appreciate and take action. So that’s the main purpose, and the kids are loving it.”

Seventh grader Ruby Gruen described one of the stations her class rotated through. “We looked through those bins over there to find insects and stuff,” Gruen said. “And I think it’s important so we know what we’re drinking.”

Beneath the mature oak trees shedding an autumnal veil of leaves, Murali’s colleague Jen Clark was busy teaching her students the history of the Kletzsch Dam and the importance of the fishway being built on the far shore.

Explained her seventh grader Mason Homa: “They are building an area for a fish to go through ‘cause some fish aren’t strong enough to go through the current and can’t jump. Most fish have to jump and migrate to the waters to lay their eggs.”

Educating the next generation of humans is important, said Aaron Schiller, WDNR’s fish biologist, because the return of sturgeon will ultimately depend on all of us.

“Spawning habitat, protecting those adults, and water quality are three big things for getting this population rehabilitated,” Schiller said. “Awareness is going to be big.”

Riveredge’s Mary Holleback, instrumental in the annual rearing of young sturgeon since 2006, is optimistic Milwaukee sturgeon advocates will make a difference.

“We will have people who will at least be aware and go to the boat landings and wherever and educate people that this is in fact an unusual fish,” she said. “They are very unique. They are very ancient. They have not been in the Milwaukee River for so many years. And this is a process of trying to reintroduce them. We hope people will be respectful of them and leave them be!”

Decades of Native American leadership and the work of teams of science-based fisheries managers have led to the point where, every September at Sturgeon Fest, parents wait in long lines to donate money for the chance for their kids to release a baby sturgeon at the water’s edge.

Jeff Mercer helps his son Lucas release a sturgeon down the halfpipe and into the Milwaukee harbor slip on Sept. 24, 2023. Photo courtesy Jamie Mercer.

In 2023, one family was Jeff and Jamie Mercer and their son Lucas. First grader Lucas opted to send his sturgeon down the PVC-halfpipe slide into the harbor.

“We love going to Sturgeon Fest,” said Jamie Mercer. “Lucas attends Riveredge Outdoor Learning Elementary School where some of the sturgeon are raised. Students have the opportunity to visit the sturgeon at school and learn about them as they grow into fingerlings. It’s really exciting for him to come to Sturgeon Fest to release the sturgeon and be an active part of the process he’s learning about in school.”

Each fish that plops in is a down payment on the future: pennies plinking into the Lake Michigan piggy bank.

And a reminder that we are all part of the sturgeon story.

With almost a half-billion dollars expected to flow into Milwaukee Estuary Area of Concern cleanup projects over the coming years, it’s a leveraged investment.

The work to bring back sturgeon—through fish passage, habitat improvement, and sediment cleanup projects—ultimately benefits much more than one species, said Milwaukee County Parks’ Natalie Dutack, including our own.

“We’re talking about enhanced populations of native fish,” said Dutack. “Fish that people love to fish for. Fish that people rely on for food—subsistence fishermen. We’re also talking about pure recreational enjoyment. And obviously, I say all that, and I always like to say we’re also talking about better lives for the fish themselves.”

If they survive, sturgeon released today—the size of first-grader Lucas’ hand—could grow to seven feet and endure into the 22nd century.

“There’s nothing bigger out there. They’re bigger than you or I,” Holleback said. “Believe it or not, some fish from the ’40s are still coming back [in the Wolf/Winnebago system]. These things live till they’re 150 years old. The females can go to 180 years.”

What will the story of the Milwaukee River look like for those sturgeon in 50 years—in the 2070s—when today’s seventh graders will be in their early 60s?

“I feel like it’s going to be cleaner,” said a Glen Hills seventh grader exploring the Milwaukee River at Kletzsch Park, “maybe.”

Photos by Michael Timm

Photos

This is the third story in a series by Michael Timm, a Milwaukee Water Storyteller for the nonprofit Reflo. He holds a 2013 master’s degree in freshwater science from UW-Milwaukee. He previously wrote and edited for the Bay View Compass newspaper.

This project is funded by the Wisconsin Department of Administration, Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the terms and conditions of Wisconsin Coastal Management Program Grant Agreement No. AD239125-024.21. Funded by the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office for Coastal Management under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant # NA22NOS4190085

Water Series

-

How Salt Is Polluting State’s Waters

Mar 29th, 2024 by Michael Timm

Mar 29th, 2024 by Michael Timm

-

The Return of the Sturgeon

Jan 31st, 2024 by Michael Timm

Jan 31st, 2024 by Michael Timm

-

How the Kletzsch Fishway Was Created

Jan 19th, 2024 by Michael Timm

Jan 19th, 2024 by Michael Timm