The Return of the Sturgeon

Innovative, decades-long effort brings extirpated species back to the Milwaukee River. Second in a series.

Cheryl Masterson, WDNR fisheries supervisor with the Lake Michigan-South team, holds an adult lake sturgeon captured during a dip net survey in the Milwaukee River. Photo courtesy of Aaron Schiller from his “Lake Sturgeon Rehabilitation | Milwaukee River, WI” 2023 presentation.

Long before there were Great Lakes, there were lake sturgeon.

With bodies like torpedoes, sturgeon entered the Great Lakes as drainage basins flexed following the recession of the continental ice sheet some 14,000 years ago.

The species has endured for over 100 million years.

Growing as large as seven feet long, several hundred pounds, and over 150 years old, these gentle giants once marauded the bottoms of the Great Lakes to feed, swimming upriver to spawn in spring. Sturgeon swim with bellies close to benthic (bottom) surfaces, using their barbels (fish whiskers) and sensitivity to electric fields to find prey below, which they vacuum up through protruding tubular mouths. That direct connection to organisms low on the food chain makes the sturgeon a great indicator for water and sediment quality.

“They’re like a barometer for how our Great Lakes are doing,” said Mary Holleback, educator and science manager for the nonprofit Riveredge, who has assisted Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) in a unique program rearing lake sturgeon for the past 17 years. “In other words, they need clean, livable water with high oxygen, not much pollution. They tell us how the overall environment is doing, just by their presence or their absence.”

Mary Holleback, educator and science manager for the nonprofit Riveredge, has assisted Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) in a unique program rearing lake sturgeon for the past 17 years. Photo by Michael Timm.

In the 20th century, absence characterized the sturgeon’s story more than presence. Once revered and consumed by Wisconsin’s Native peoples, lake sturgeon almost did not survive European Americans in the 19th century—suffering a trifecta of abuse: overfishing, pollution, and habitat loss tied with the construction of dams that blocked their passage to spawning waters.

But that was not the end of their story.

Thirty-eight miles upstream from the Kletzsch fishway, an unassuming pump draws Milwaukee River water through a buried hose like a kid sucking on a soda straw.

Every May through September, the three-inch hose delivers its liquid payload 350 yards up a wooded hill, through two 600-pound filters, and into a trailer—one of six “streamside rearing facilities” surrounding Lake Michigan. Inside, aerated with oxygen injected from from cylindrical gas canisters, the river water circulates through four periwinkle-blue basins mounted to the trailer walls, two per side.

In late summer 2023, about 500 fingerling lake sturgeon prowled these open-air “raceways” like miniature sharks. Each fish was about the length of a cell phone and half as wide. Most had dark backs, a few albino. Looking down, the effect suggested an undulating M.C. Escher print.

If these sturgeon had looked up, they might have seen a giant careworn face beyond the periodic rain of chopped krill and carefully apportioned bloodworms, the larvae of midges. Mary Holleback has doted on generations of baby sturgeon here like a concerned nursemaid, a role she fell into in 2006.

“It was really the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians up in Michigan that figured out how to do this in a streamside rearing facility and they passed it on to Michigan DNR who passed it on to Wisconsin DNR,” Holleback said. “All of us have been doing this for about the same length of time. All of us have the same quota somewhere between 1,000 and 1,500 fish per year. Not more than that because they don’t want any of these fish to swamp the gene pool out in Lake Michigan.”

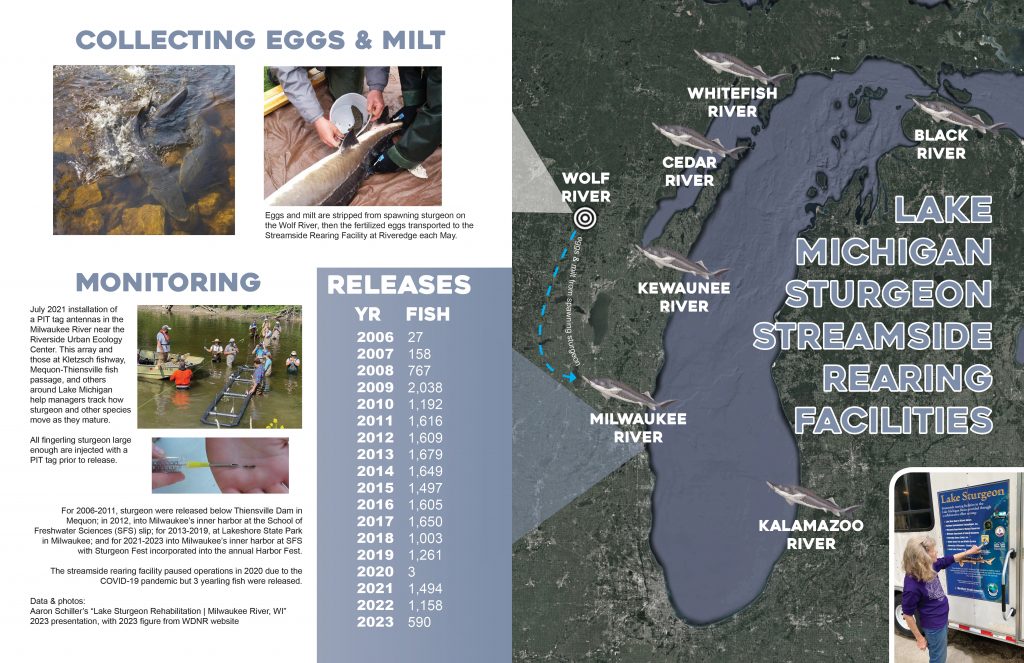

For 2006-2011, sturgeon were released below Thiensville Dam in Mequon; in 2012, into Milwaukee’s inner harbor at the School of Freshwater Sciences (SFS) slip; for 2013-2019, at Lakeshore State Park in Milwaukee; and for 2021-2023 into Milwaukee’s inner harbor at SFS with Sturgeon Fest incorporated into the annual Harbor Fest. The streamside rearing facility paused operations in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic but 3 yearling fish were released. Data & photos: Aaron Schiller’s “Lake Sturgeon Rehabilitation | Milwaukee River, WI” 2023 presentation, with 2023 figure from WDNR website.

The 25-year project, planned through 2031, aims to undo over a century of abuse: reintroducing lake sturgeon to Lake Michigan waters and helping them once again call the Milwaukee River home.

The fish imprint on the water they are raised in, Holleback explained. “The fish actually smell the chemistry of this water, the Milwaukee River water.” Decades later, when these slow-maturing fish are ready to reproduce, the sturgeon rely on that scent memory to home in on spawning waters.

There is evidence this approach is working in the Milwaukee River. “For the first 10 or 15 years of this project we did it all based on faith,” Holleback said. “They told us that they would imprint on Milwaukee River water and come back to the Milwaukee River to spawn, but there was no proof of that from this project till some of the males from this project starting coming back two years ago [2021].”

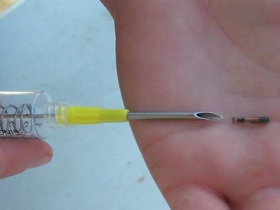

Because each sturgeon released is fin-clipped and PIT-tagged, managers are gaining a better understanding of their movements.

“Once they get to be about three years old, then they get kind of wanderlust and head out into the big lake and are found all over,” Holleback said. In 2011 one of their fish released in 2008 turned up in Whiting, Indiana and another a few weeks later in Big Bay De Noc in Upper Michigan. “So they get out all over the lake and only find their way back when it’s time to spawn. That’s pretty exciting.”

Raising broods of young fish is a labor of love. Inside the Riveredge trailer, volunteers take shifts feeding the sturgeon on little conveyor belts that dole out protein diced from frozen blocks of food. “It’s all based on how many fish and their weight, so that we know we’re not overfeeding them,” Holleback said, “and we try to make the pieces small enough to get in their mouth.”

Sometimes the fish get sick. Illness killed about half the fish in 2023. A WDNR veterinary report identified no viruses of concern but did find a columnaris bacterial infection, skin disease, gill damage, and water mold infection. Holleback compared the sturgeons’ crowded circumstances to the spread of COVID-19 among humans packed in public spaces.

There are good years and bad years for sturgeon hardiness. In 2023, all the fish reared at Riveredge descended from the genetic mingling of eight females and five males.

Each year’s fingerlings grow from eggs and milt (sperm) collected every spring from naturally spawning fish in the Wolf River near Shawano. Spawning fish the size of logs in shallow waters is a spectacle. As females release eggs, males sidle up alongside, vibrate their tails, and release sperm. “They [WDNR fisheries managers] actually strip the eggs, and get the milt, and mix the eggs and milt together up there so they come here [Riveredge streamside rearing facility] fertilized the same day,” Holleback said.

Until completion of the Kletzsch fishway, the annual sexual drama unfolding in the Wolf River had a scant stage on which to play in the Milwaukee River. But after 17 years of downstream releases the first actors are in the wings.

And eager.

Based on gut contents of sturgeon that have washed up on Lake Michigan beaches, it’s now known that sturgeon are feasting on round gobies, an invasive fish species increasingly integrated into Great Lakes food webs, said Aaron Schiller, WDNR fisheries biologist.

“They’re readily available for the sturgeon,” Schiller said. “Their [gobies’] defense is kind of camouflage and sit still on the bottom. As the sturgeon swims over—those barbels—they know they’re there. They just suck ’em right up.”

The ample availability of round gobies as food may have increased the growth rate of the Lake Michigan sturgeon population, meaning they could be reaching sexual maturity years earlier than previously projected.

If so, more Riveredge sturgeon alumni should soon be pushing upstream in pursuit of their reproductive dream—making efforts to expand the sturgeon’s portfolio of spawning habitat options more vital.

“We’re not in control of the flow of the water,” said Schiller. “They’re very picky on the velocity they need for spawning. [But] We can work on substrate. So if they need a certain size rock and the velocity and the depth is there, I can put in rock there.”

Schiller also hopes to provide advice to riverfront property owners who may be on an outside bend—preferred by spawning sturgeon—who are looking at landscaping. “And say, ‘If you ever want to re-landscape here, we suggest this type and this size of rock. If you’re interested, we may be able to get some grant funding to help out with that,’” Schiller said. “Working with partners is essential in all this stuff.”

Jay Wesley, Lake Michigan Basin Coordinator for Michigan DNR, works with interstate partners and tribal nations to manage sturgeon reintroductions to Lake Michigan.

“The reintroduction efforts have been going on for over 20 years, and we are now starting to see mature adults coming back to the rivers that they were released in,” Wesley wrote. “This is a great sign that the efforts put in over the [years are] working. It will be another 20 years to determine if adult populations increase in our river systems to become self-sustaining. That is the goal of the current stocking and habitat improvement programs.”

The work raising tiny fish in a tiny trailer in tiny Newburg, Wis. has already attracted global attention. Like in 2006—when a tour bus of Azerbaijanis showed up at Riveredge unannounced.

“I was at the end of the driveway and was about to pull out and this bus—I mean a big fancy bus—pulls up,” Holleback recalled. “You never see that out here, maybe a school bus. The guys got out in tuxedos and I was like, What in the—? Two people in the group spoke English. The rest all spoke Russian. I was on the phone with Brad [Eggold with WDNR Fisheries], like, What is this?”

The Azerbaijanis had just come from Lake Tahoe in California, Eggold told her, and he would be there soon to give them a tour. They had been touring fish hatcheries across the United States to inform their own efforts to restore native beluga sturgeon—whose caviar goes for a thousand dollars an ounce, Holleback said. “They were trying to see how this was done.”

One lesson for the Azerbaijanis: It takes a village to raise these fish.

Holleback credits the dedication of volunteers, some who have invested over a decade of their lives to take care of these fish. “The volunteers treat these like they were their children,” she said. “They have names for them. There’s one that has two noses. Who would notice that? I wouldn’t. There’s 500 fish in here but they know: ‘Yep, it’s up there.’”

Holleback and a short list of WDNR fisheries staff are literally on call May through September. Someone has to respond whenever there is an alarm at the trailer from a power outage, clogged filter, or pump failure. Sometimes that means responding in the middle of the night—if the aeration tanks go down, an entire year-class of fish could suffocate for lack of oxygen.

In the early years, frequent power failures meant WDNR fisheries personnel would have to drive up from Greenfield Avenue in Milwaukee, an hour away, to rescue the fish. “So we’d be running to the river with buckets of water and running back up with buckets of water to keep them going,” Holleback recalled. “We’d operate things off of our car batteries. It was just a mess.”

A backup generator was installed, but the need for vigilance remains. When heavy rains flush sediment into the turbid river, it can compromise the filters.

Holleback recalled a recent alarm that kept repeating. “Every two hours you had to be down here. I got the daytime shift. Brad got the one from six to midnight, and poor Keith, who lives here, got the midnight to six in the morning,” she said. “His wife was ready to divorce him!”

The cause demands an uncommon devotion of sturgeon caretakers. But the reward could mean bringing back a species that historic human activity pushed to the brink of extinction.

With ongoing rearing-and-release efforts plus the removal of stream impediments, the goal of a naturally reproducing lake sturgeon population in the Milwaukee River seems within reach.

“By the time we’re done we will have have released about 30,000 lake sturgeon from this facility alone,” Holleback said. “And this is one of only six on Lake Michigan… So there’s a really good chance that lake sturgeon by that time [2031] will be well established in Lake Michigan and coming back to all these various rivers. It’s all very promising.”

Photos by Michael Timm

Photos

Illustrations

This is the second story in a series by Michael Timm is Milwaukee Water Storyteller for the nonprofit Reflo. He holds a 2013 master’s degree in freshwater science from UW-Milwaukee. He previously wrote and edited for the Bay View Compass newspaper.

This project is funded by the Wisconsin Department of Administration, Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the terms and conditions of Wisconsin Coastal Management Program Grant Agreement No. AD239125-024.21. Funded by the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office for Coastal Management under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant # NA22NOS4190085

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Water Series

-

How Salt Is Polluting State’s Waters

Mar 29th, 2024 by Michael Timm

Mar 29th, 2024 by Michael Timm

-

Why Do We Care About The Sturgeon?

Feb 15th, 2024 by Michael Timm

Feb 15th, 2024 by Michael Timm

-

How the Kletzsch Fishway Was Created

Jan 19th, 2024 by Michael Timm

Jan 19th, 2024 by Michael Timm

Great article, thanks for this informative update. I love the imagry, “undulating M.C. Escher print”! But here’s a question. The “sexual drama” involving spawning (having sex), and milting (releasing of sperm) after vibrating their tails sounds an awful lot like the mammalian equivalent of penile stimulation and ejaculation, possibly with the pleasurable sensation of orgasm. Have any studies involving fish such as sturgeon experience orgasm? I realise there’s no direct way to ask the male fish if milting– or anything else, like eating certain types of food, swimming back to the rivers of choice, temperature preferences, etc.– may be pleasurable, but indirect evidence such as brain studies, Pavlovian reward paradigms, etc. may provide some evidence or their seeking pleasure and avoiding pain or other displeasures. I don’t mean to anthropomorphize sturgeon behavior, but many male vertebrates like fish due have penises or cloaca…