How To Grow Wisconsin’s Wealth Gap

The Institute for Reforming Government offers a plan to help the wealthy.

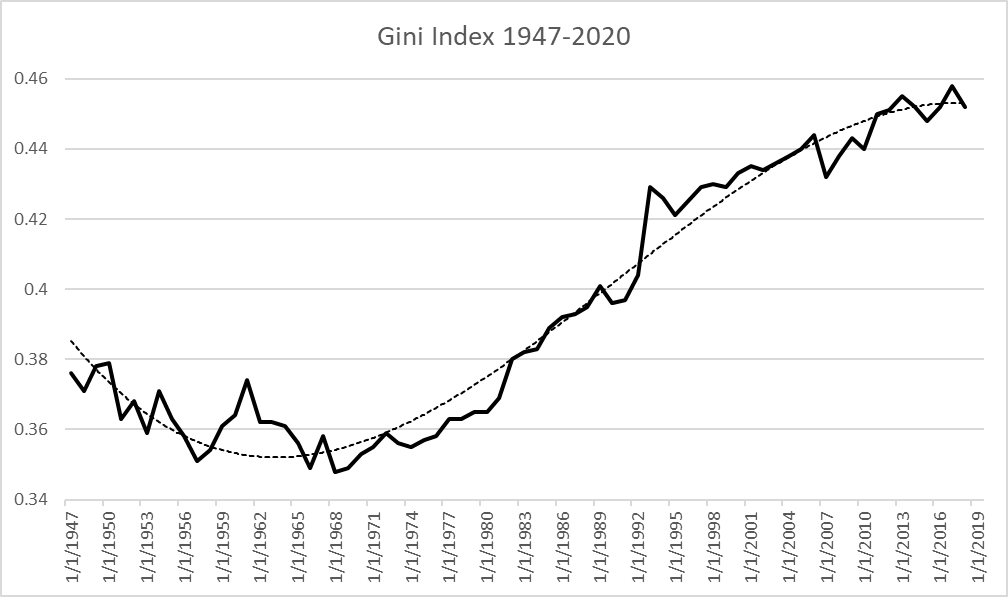

Since the 1960’s, financial inequality has been growing in the United States. One common measure is the Gini index of income inequality, which is shown below. If every family in a nation had the same income, the Gini index would be zero. If one family managed to capture all the income, the index would be one.

The solid line shows the Index from year to year, as calculated by the US Census Bureau. The dotted line is the long-term trendline.

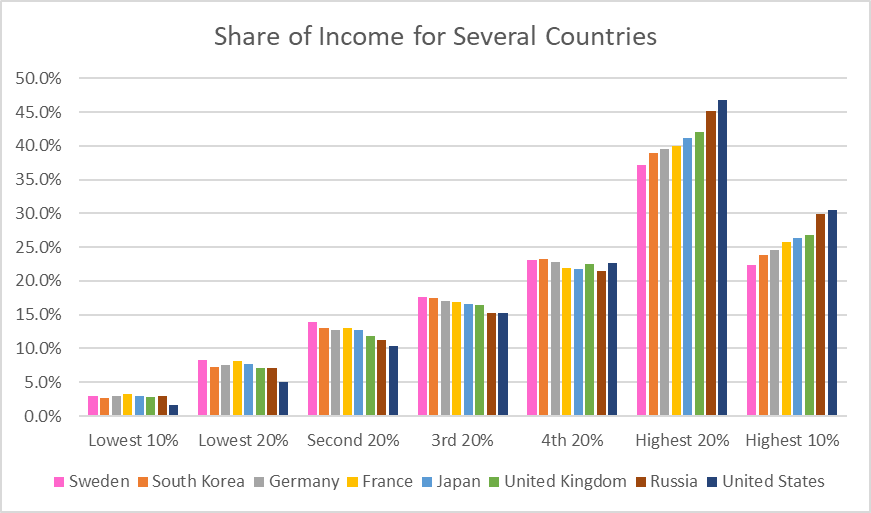

The causes of this deeply disturbing trend range from government policy to global trends, such as the migration of much manufacturing from wealthy countries to countries with lower pay rates. The impact of each can be debated, but it’s clear the movement in the direction of increased inequality has progressed further in the United States than in nations generally considered our peers. The chart below compares the share of national income that goes to each quintile of the American population to six peer nations, as well as to Russia. It also includes the share that goes to the highest and the lowest 10% of each country.

Of these countries the United States has the most inequality. In this race, Russia is our closest competitor. The upper 10% of American households has income that is 18 times that of the lowest 10%. With the exception of Russia none of the other countries has a ratio of highest to lowest 10% that exceeds 10.

In recent years, America’s increased income and wealth inequality has generated growing concern from economists and others who worry about the future of the nation. The fact that I could generate the income shares shown above reflects this concern, as there is now so much data available by researchers analyzing this trend.

Wisconsin was long a state with policies to promote equity. It was the first state to implement a progressive income tax. It is called progressive because the tax rate increases as income goes up, reflecting the taxpayer’s ability to pay the tax.

But the state has for some time had a lobbying effort to increase inequality in Wisconsin. Under the umbrella of something called the “Institute for Reforming Government” (IRG) three right-wing lobby groups, Americans for Tax Reform, Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce, and Americans for Prosperity-Wisconsin, recently called for eliminating Wisconsin’s income tax. IRG’s staff and supporters are thoroughly embedded in the right-wing ecosystem, having served in roles at organizations like the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty. Former board members include former governor Scott Walker and former Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Daniel Kelly, and the current board includes Jim Villa, former campaign manager and chief of staff for Walker.

This proposal was accompanied by a report from Noah Williams, a UW-Madison economics professor and founder of the Center for Research on the Wisconsin Economy (CROWE). Williams has established himself as an advocate of the proposition that the way to prosperity is reducing taxes on rich people:

I consider a tax reform to eliminate the state income tax and make up some of the lost revenue by increasing the sales tax. … my baseline reform eliminates the income tax and increases the sales tax rate from 5% to 8%. … my estimates are in line with others in the literature.

This is clearly a recipe to make Wisconsin’s tax system more regressive. But that does not appear to be a concern of Williams. Nowhere in his report does he acknowledge that this proposal would make Wisconsin taxes more regressive, thus further aggravating inequality.

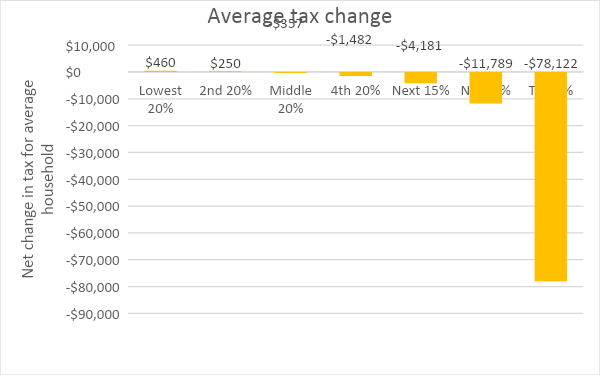

The next table, based on analyses from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and the Wisconsin Budget Project, shows the estimated change in taxes depending on the taxpayer’s income level. Members of the top 1% would enjoy an average tax decrease of $78,000. In contrast, those in the bottom 40% would expect to have a tax increase, based on the assumption that the homestead and child credits would go away along with the income tax.

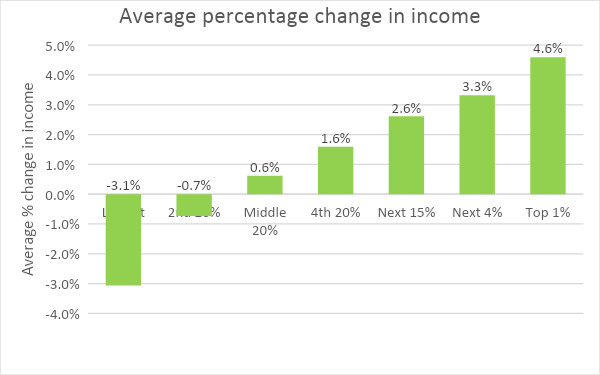

The next graph translates these tax increases and decreases into the effect on income. Those in the lowest income quartile would see a net income decline of about 3%, compared to an increase of 4.6% for those in the top 1%.

Note that Williams acknowledges the increase in the sales tax from 5% to 8% would not be sufficient to make up for the revenue lost by eliminating the income tax. Most likely the Legislature would make up for this by further cutting shared revenue, so that cities, towns and counties would face the choice of defunding the police or further cutting support for libraries and parks.

But did business investment increase, even if the act did not pay for itself? Post-act studies found that “it had little impact on business investment through 2019.” This suggests that Williams’ expectations for the results of ending Wisconsin’s progressive income tax are likely to prove optimistic.

Finally there is the infamous Kansas experiment that eliminated most taxes on the assumption that increased business activity would make up for lower rates. Instead, it led to economic disaster as underfunded schools were forced to close early. As a result, voters in strongly Republican Kansas for the first time in years elected a Democrat as governor.

One can easily see why organizations supporting the so-called “reform” that would eliminate Wisconsin’s income tax would find it appealing. Their members would benefit from shifting the costs of government away from wealthy people. And the wealth gap in Wisconsin would grow accordingly.

Data Wonk

-

Why Absentee Ballot Drop Boxes Are Now Legal

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Two additions to this excellent piece. First, Wisconsin increasingly fits the definition of a “plutocracy,” with Republican governments firmly under the control of a handful of super-wealthy people. In this context, the fake Koch phone call to Scott Walker and the orders given by Diane Hendricks to get rid of unions were, in reality, a big deal.

Second, in his recent book, “The Great Leveler”, the historian Walter Scheidel points out that no society with our levels of inequality has ever escaped mass violence. The violence is the great leveler, eliminating the vast extremes that the United States how shares with only three “developed” economies, Russia, Brazil and Mexico. Not exactly what you would describe as “nice company.”

That income profile: a tiny sliver of extreme wealth, another of great wealth, declining middle and working classes, and entrenched poverty. In our country, all masked by race-driven culture wars.